Happy 105th birthday to the

Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom

It’s a good time to reflect on the virtues of feminist internationalism

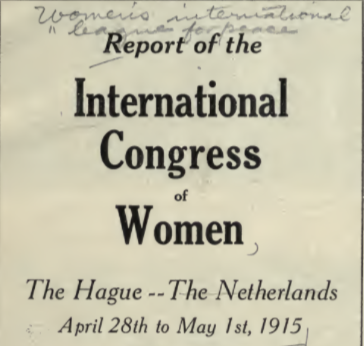

It seems especially appropriate to mark today’s 105th anniversary of the Geneva-based Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which met for the first time on April 28th, in 1915. I say this because, as we grapple with a global pandemic and the conflicting political pressures it has brought to bear on nation-states and our tenuous global infrastructure, more and more news sources have noticed something interesting: that the countries that are among the most successful in balancing firm, knowledge-based responses to the medical crisis with compassion, empathy, and stability, are those nation-states led by women.

It seems especially appropriate to mark today’s 105th anniversary of the Geneva-based Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which met for the first time on April 28th, in 1915. I say this because, as we grapple with a global pandemic and the conflicting political pressures it has brought to bear on nation-states and our tenuous global infrastructure, more and more news sources have noticed something interesting: that the countries that are among the most successful in balancing firm, knowledge-based responses to the medical crisis with compassion, empathy, and stability, are those nation-states led by women.

“Looking for examples of true leadership in a crisis?” asked Avivah Wilenberg-Cox in the pages of Forbes in early April. “From Iceland to Taiwan and from Germany to New Zealand, women are stepping up to show the world how to manage a messy patch for our human family. Add in Finland, Iceland and Denmark, and this pandemic is revealing that women have what it takes when the heat rises in our Houses of State.” It’s a view echoed last week by Jon Henley and Eleanor Ainge Roy in The Guardian. While many male leaders have done well too, they point out, most of the world’s female leaders have excelled: Angela Merkel, Jacinda Ardern, Mette Frederiksen, Tsai Ing-wen, Erna Solberg, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, Sanna Marin, and even Silveria Jacobs, the prime minister of the tiny Dutch Caribbean Island of Sint Maarten, have all shown startling success in managing the pandemic in their respective countries.

Both of these articles insist that we can’t make generalizations about men and women under these conditions. Sociologist Kathleen Gerson from NYU pointed out that women tend to be elected in countries where gender differences are already minimized and trust in government is higher, while men who lead more “traditional” societies find it harder to escape from gendered expectations of what a male leader should be like.

That said, the discussion of the gender dimensions of national leadership is in part a function of the long struggle for women to make their presence felt in politics precisely because many of them believed that women, qua women, could change national and international affairs. This claim has been a complicated one, sometimes veering toward an essentialist argument that women were innately more peaceable than men, and their access to the vote would help “civilize” military-industrial societies. The debate over women’s natures, in the end, has been more complicated than that, but in the international sphere, it was partly set in motion by the formation of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, or WILPF as it is known today.

This brings us back to The Hague in the spring of 1915. The great Dutch “city of international peace and justice,” perched in the edge of the North Sea, and fat with the profits of the Dutch East India Company, was then sandwiched between the Triple Entente and the Imperial German army. Blockaded at sea by the British navy and pinned on its eastern frontier by Kaiser Wilhelm’s Reich, Dutch neutrality was always a perilous thing. So, what brought over 1100 women from across Europe and the North Atlantic world to the city at a time when travel was so dangerous?

They met to try to stop the slaughter. Women’s transnational organizations had been active from the outset of the July crisis. The International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) had been founded only ten years earlier, but in July 1914 it sent a “Manifesto of Women” to the British Foreign Office and all foreign embassies in London. Other female and pro-suffrage groups followed: The British Union of Democratic Control (UDC), followed by the Dutch Anti-Oorlog Raad (Dutch Anti-War Council), the Fellowship of Reconciliation (UK), and then the Women’s Peace Party in the U.S., formed in January 1915 and led by Jane Addams. The Germans also formed the Bund Neues Vaterland, and the Swiss created the Union Mondial de la Femme.

But it was thought that these more or less national or local organisations could not be effective unless they could find “international expression”, and ”that women as such had a special note to strike which they alone could sound.” Thus, isolated women in different countries began finding a different expression, aided by publications that still occasionally crossed borders: the IWSA’s journal, Jus Suffragii, the BritishLabour Leader, and the German Social Democratic Party’s Vorwaerts.

It was the Hungarian international secretary of the IWSA, Rosika Schwimmer who first proposed, early in the war, a “Conference of neutrals for mediation”, and she traveled from London to the U.S. to convince Woodrow Wilson to lead it, lecturing across the country wherever she was invited. A similar tour by British suffrage activist Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence further awakening American women to this idea, and at least one Canadian. Julia Grace Wales was a Québec-born Shakespeare instructor at the University of Wisconsin. Over her Christmas vacation home to the Eastern townships in 1914-15, she drafted an idea for what she called “Continuous Mediation without Armistice,” and circulated it to Wisconsin peace groups. It became the de facto peace position of most U.S. peace organizations by 1915 and later the basis of the Henry Ford-funded Stockholm Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation in 1916.

Meanwhile, in November 1914, a number of prominent British women signed Emily Hobhouse’s “Letter of Christmas Greeting” to German women, followed by a series of cross frontier appeals by various women, including one from German lawyer and feminist Lida Gustava Heymann entitled, “Call of the Women of Europe.” Socialist women met in Berne in March 1915 and issued a Peace Manifesto of their own. The secretary of the Socialist Women’s International, Clara Zetkin, had naturally defined the war as a symptom of capitalism’s quest for world domination but she placed socialist women’s peace activism in feminist terms as well: “If men must kill, it is women who must fight for life. If men remain silent, it is our duty to speak out.” Paradoxically, precisely because women were not seen as having full political agency (or voice), representatives from all sides of the war were able to gather in Switzerland. The Berne meeting, modest thought it was, marked the first international conference that included “citizens” from both alliances and the neutral countries.

The association of women with peace activism profoundly divided the suffrage movement because it posed risks that, at the very moment women might claim their right to political representation, some of them were taking action against the grain of expected patriotic duty on precisely the ground that women were different from men. As such, the IWSA backed out of holding its scheduled biennial congress in Berlin in 1915 and started to distance itself from those of its membership who saw pacifism as women’s peculiar duty to the international order. Mary Sheepshanks, the outspoken British editor of the IWSA’s journal, Jus Suffragi, and a close friend of Bertrand Russell, dissented from this official stance, and used her position to promote peace as a women’s issue, juxtaposing internationalism and patriotism in feminist terms: “Internationalism rests on the feeling and knowledge that humanity is a bond stronger than mere boundaries of races and states, that above all the superficial barriers in the Western world, a common civilization that unites men and their dependence and their mutual obligations can and should be a way to unite them in a collaboration for the common tasks of civilization.”

In this sense, internationalism was a way to signal the idea of collective self-consciousness that transcended the artificial (a word internationalists of different types used to establish a boundary between what was natural and what was a function of the exercise of domestic power hierarchies) collectivities of race and nation, something more akin to cosmopolitanism but which preserves space for the cultural attachment to nation that operationalizes the concept of political rights and duties. In Sheepshanks’ opinion, internationalism as a higher location of political attachment was sustained during the Great War as one of the universal treasures that feminist women were trying to keep alive, as living proof of these ideals as political practice. Jus Suffragii was one of the few international organs that produced reports of political activity from both sides of the war.

And women were indeed prepared for this role. The British feminist and internationalist Emily Hobhouse took this view when she wrote: “The International Suffrage Alliance had not in vain been training women for years from all parts of the world to know and work with each other, and though officially it stood aside, yet one of its most noted members—Aletta Jacobs—belongs the honour of concentrating and shaping the ardent yearning of women of all lands for peace and justice.”

Alletta Jacobs was then the president of the Dutch Association for Woman’s Suffrage, and its Committee for International Affairs. From that position, she invited all women who were interested in the cause of peace to come to The Hague in April 1915. Jacobs used the IWSA’s mailing list, arguing that it was never more important for the women of the world to meet: “the women have to show that we at least retain our solidarity and are able to maintain mutual friendship.” Jacobs still considered this to be the international business meeting of the IWSA, but one in which women could also freely discuss the situation of the world.

At this point, British suffragist Chrystal Macmillan privately canvased members of the IWSA to suggest that after the “business meeting”, delegates could stay to hold another on issues of international arbitration, public control of foreign policy, and the prospects for peace. If the Alliance didn’t want to sanction this kind of meeting, internationalist women could convene it anyway. Once the IWSA formally signalled that it would not back anything that moved beyond the issue of suffrage, Jacobs called a preliminary planning meeting in Amsterdam on February 12 and 13 with a view to following Macmillan’s proposal. The meeting had representatives from both sides of the war (Belgium, Britain, Germany) and one neutral (Netherlands).

But the most important country still missing at that point was the United States. It was the neutral state that most held the hopes of the world peace movement. While President Wilson continued to rebuff efforts by peace groups to lead mediation efforts, the formation of the Women’s Peace Party in Washington in January 1915, with future Nobel Peace Prize winner Jane Addams at the helm, was profoundly encouraging for Jacobs and her organizing committee. Addams accepted the invitation to The Hague and brought a large American delegation with her (47 either crossed the Atlantic or arrived from other European locations), including another future Nobel Laureate, Wellesley College economist and sociologist Emily Greene Balch. This gathering of neutral and belligerent citizens during the war was only possible because of what Balch noted in a letter home: that women had a peculiar locus standi as non-citizens, as people subjected to decisions over which they had no say, to speak against war.

About 1136 women (most of them Dutch, of course, but 12 countries were represented) met between April 28 and May 1. There were over 1500 at its opening and because this was too large a number to fit into the Carnegie-built Peace Palace, the Congress had to gather in the Dierentuin, the great hall of The Hague Zoological Gardens. Not all European feminist groups were represented, even by correspondence: the principal French suffrage groups argued that the object of suffrage was to participate in the public life of their nation, not abandon it to the ether of internationalism and pacifism. The Conseil National des femmes françaises (CNFF founded in 1901) and the Union française pour le suffrage des femmes (UFSF, founded in 1909), issued a counter-manifesto. “We have finally understood that our primary obligation amidst the great misery that afflicts our country, is to pull together and become one single and solid family, the family of la patrie.’’ Marguerite de Witt-Schlumberger, head of UFSF, sent five sons to the front. Jane Misme, editor of the feminist journal, La Française, attacked pacifism “as orchestrated by Berlin.” French feminists, she tried to claim, wrongly, were never internationalists.

The Hague Congress debated war and peace for three days, and then issued a Manifesto filled with what would later become the standard positions of liberal and socialist internationalism: arbitration, the right of self-determination, democratic control of foreign policy, disarmament, the rejection of all “annexationist” war aims, the channeling of international public opinion through a new society of nations, and, most of all, the international enfranchisement of women (more on that later). Despite the common currency of most of these ideas, they were targeted in the press for their gender (“a screeching sisterhood,” “twittering sparrows,” “babbling,” “hysterical”). They were ridiculed for being both excessively feminine for international politics (women are too sensitive to understand war) and too unwomanly for domestic politics (they were stepping into political areas that demeaned their femininity).

The Hague Congress did two things of historic significance. First, it formed itself into an international organization called the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace (ICWPP) based in Amsterdam during the war. Jacobs was its secretary but Addams became the organization’s president from her home base in Chicago. In 1919, at its next Congress in Zurich, the ICWPP changed its name to the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and established a headquarters in Geneva to lobby the newly formed League of Nations. Addams was still president but day to day operations were run by fellow American Balch as its full-time secretary. Today WILPF retains offices in both Geneva and New York City, but The Hague Congress is why it marks today as its founding moment.

The second thing The Hague Congress did was to send two delegations of women to the capitals of Europe in May and June 1915 to circulate its idea of “continuous mediation”. Addams, Jacob and Schwimmer met with the leaders of Netherlands, Britain, Germany, Austro-Hungary, Italy, France, and Belgium. Balch, Schwimmer, and Chrystal Macmillan from the UK, went to Scandinavia and Russia (although Schwimmer was refused entry to Russia). This in itself was extraordinary, and while these envoys were of course unable to stop the war and were subject to ridicule in the patriotic press in their home countries, their peace proposals were received with, for the most part, respect and seriousness. According to Addams, Austrian Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh remarked at their meeting: “You are the only sane people who have been in this room for ten months.” Wilson, too, when Addams took The Hague resolutions to him later in the summer, stated that they were “by far the best formulation which up to the moment has been put out by anybody.”

There is some debate amongst historians, of course, about how influential The Hague resolutions were on the subsequent trajectory of Wilson’s internationalism, but WILPF undoubtedly represented an influential internationalist community actively lobbying the administration for the rest of the war. By 1919, when WILPF held its second Congress in Zurich, it still held out hope that Wilson’s internationalism would bring to the table their more radical feminist hopes, but they ended up being deeply critical of the League of Nations as it was constructed at the Paris Peace Conference, and even more hostile to the annexationist tendencies of the final terms. To them, the peace process was an abandonment of everything the internationalists had fought for during the war.

They also waited in vain for the international community to sanction women’s political rights as a constituent part of international peace. While the end of the war brought suffrage to more women in the Atlantic world, it came fastest in those states that had been neutral or, as in Russia and to some extent Germany, had experienced a socialist revolution. Stalwart members of the Entente France and Italy only granted women the vote after the Second World War. There was no automatic correlation between women’s patriotic loyalty to the warring state and their emancipation as full citizens.

The abject failure of WILPF to stop the war or to secure a more just peace puts it in the same company of all other liberal and socialist international groups. But The Hague Congress nevertheless marked the start of a bona fide “feminist internationalism,” a term used at the time by the international members of the group to define what they were trying to build. WILPF’s critique of the early League of Nations—which was subjected, of course, to numerous criticisms at the time and after—was the only one that insisted its failings had something to do with gender.

What did this mean exactly, given that the term gender was not used in this sense until the 1950s?

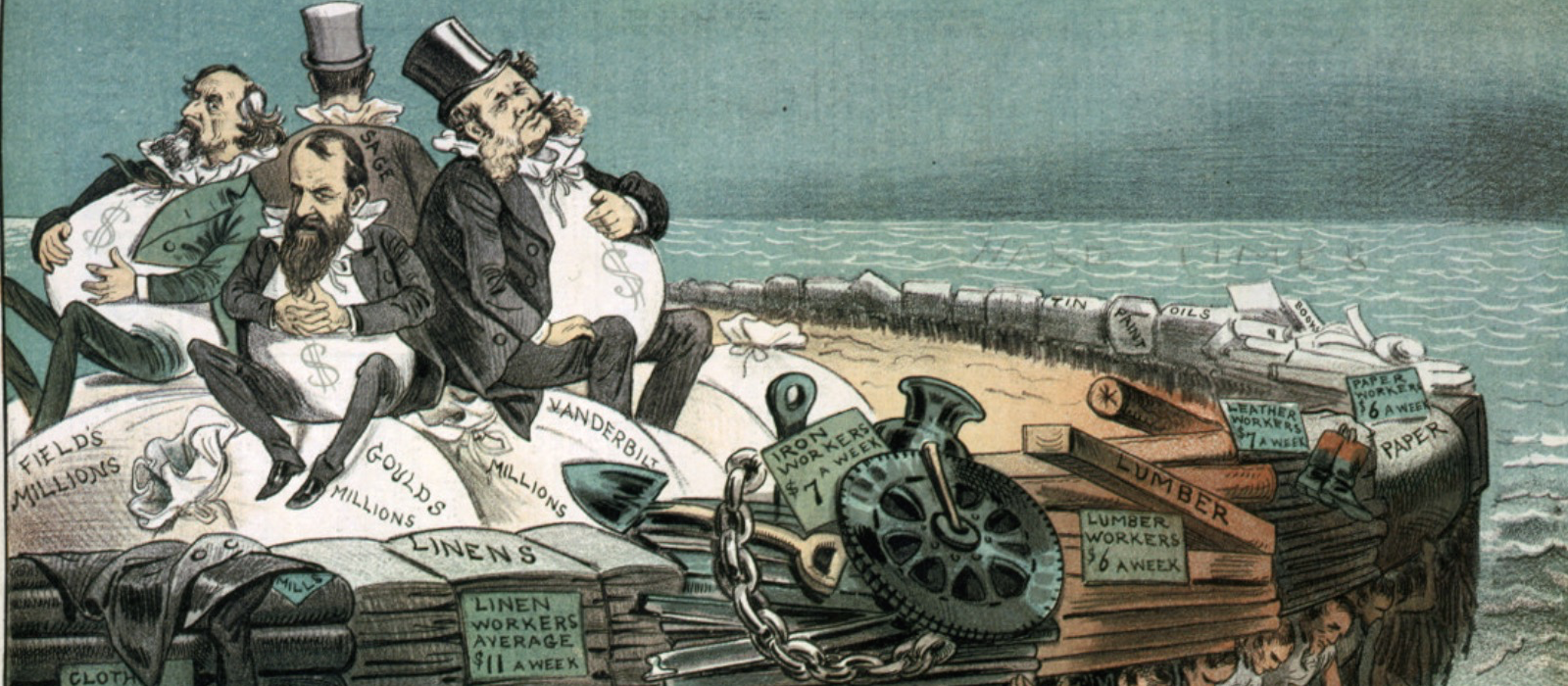

If we look at the WILPF’s early Congresses and subsequent work in Geneva, it’s clear that, just as socialists saw the meaning of international politics in terms of global class conflict, WILPF believed that the subjugation of women, starting with their political rights but including all forms of social marginalization and exclusion, reproduced a culture of male leadership that valorized militaristic nationalism and imperialism.

Their intellectual stimulus, if you will, came from two experiential sources. One was from working together as an international organization across borders during a time of war, subjected to shared forms of press ridicule along gendered lines, as well as varying degrees of police harassment. Their transnational cooperation against the grain of hyper patriotism, created an international sense of feminist consciousness, as they recognized the marginalization of women as a global phenomena, and a central part of international politics.

They knew perfectly well that most women didn’t share their pacifism, either because of patriotic loyalty or fear that pacifism would hurt suffrage. But because they identified the cruelty and waste of the war with the peculiar pathologies of nationalism, they foregrounded humanity rather than nations as the proper focus of building permanent peace; and one cannot speak of humanity without women.

The second source of knowledge stemmed from the fact that almost all of them were social workers of some type. Many of them had developed a sociological perspective on the nation-state itself. Across the North Atlantic academic world at this time, nationalism and internationalism were being studied as specific forms of social identity, and the social settlement work of Jane Addams in Chicago, the studies on immigration by Emily Balch, the challenges to marriage laws in Germany by Anita Augspurg and her partner Lida Gustava Heymann, among many others, all proposed that there was something social-psychological about nation-building that needed to be understood if we were to understand war.

But this posed a dilemma. Feminist internationalists were also radical democrats who believed that the best way for women to influence international politics was through suffrage; their assumption was not that women would automatically be pacifistic when they got the vote, but that as equal citizens, women would bring less docility to national life than they did as social and political supplicants; and men, freed of the need to repress women and thus magnify their masculinity, would be less enamored of the need for heroic violence. A feminist internationalism would transform the social role models of men and women simultaneously, releasing them both from relations of dominance that made force an international norm.

In this sense, WILPF rejected any essentialist idea that women were inherently, or biologically, more peaceable and men more aggressive and violent. It was the cultural relationship of men to women which created the destructive norms of leadership that afflicted the world. Undo that, and everyone will be better off.

What WILPF argued during the war and in the 1920s anticipated the “human security” project of the late 20th century. In incipient form, its principal tenets found their way into the UN’s Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda between 2000 and 2019, Sweden’s formal adoption to a feminist foreign policy in 2014, and even Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy in 2019. And so, for that reason, WILPF’s early history is worth remembering and understanding. It is today being retrieved by feminist international relations theorists as part of the genealogy of an alternative to the realist-idealist or liberal-radical dichotomies that have limited the way we think about international politics. It also hints, I think, at why we should not be surprised that so many women leaders around the world have handled the global pandemic so well: in crisis, the politics of humanity works better than the politics of exclusion.

Andrew M. Johnston ©

WILPF’s website is at: https://www.wilpf.org

________________________________________________________________________________________________

International Women’s Day: Emily Greene Balch

The New York Times today has run a series called “Overlooked”—15 women who deserve but never received obituaries in the New York Times. Although Emily Greene Balch was one American woman who did receive recognition in the Times when she died in 1961, she remains a remarkably overlooked figure in U.S. and international history. Below I have appended my own entry in a new collection, Opposition to War: An Encyclopedia of United States Peace and Antiwar Movements (2018).

*

Emily Greene Balch (1867-1961) was the second American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. Less known than fellow laureate Jane Addams—who described Balch as the “goodest person” she ever knew—she worked tirelessly as a self-proclaimed “citizen of the world.” She was a founding member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), serving as its first secretary-treasurer from 1919 and 1922. Thereafter, in numerous capacities, Balch devoted her life, primarily within women’s organizations, to the development of what she called a “planetary civilization.”

Balch, born outside Boston to an upper middle class family, graduated from Bryan Mawr College in 1889. After a year studying in Paris, she met Addams in 1892, and helped found Denison House, Boston’s settlement house. She studied at Radcliffe, the University of Chicago and, in 1895-96, the University of Berlin. When she returned, she was hired by Wellesley College to teach economics. In 1906, Balch declared herself a socialist, a label she qualified only after the Russian Revolution. Following two years of research, she produced the first significant study on immigration to the United States, Our Slavic fellow citizens (1910), a sociological contribution to the debates on assimilation then preoccupying the nation. Balch believed that immigration had made the U.S. a plural nation in ways that served as a model for the amelioration of nationalist animosities around the world.

The Great War underlined the painful interruption of human solidarity that nationalism induced. In March 1915, because of Balch’s expertise in the Balkans, Addams invited her to attend a Congress of pacifist women in The Hague that April. The meeting created the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace, which sent envoys across Europe to encourage neutral mediation of the war. Balch toured Scandinavia and Russia, before returning to U.S. with Addams to convince president Wilson there was widespread receptivity to American mediation. They were unsuccessful, although Wilson admitted their resolutions on a new, democratic, diplomacy were the best thing he had seen on the subject.

Balch then served as the U.S. delegate to the Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation in Stockholm in 1916. She drafted, among other things, a critique of imperialism that argued not only that it was one of the great causes of international conflict, but that Europe’s occupation of “native populations”, despite efforts to idealize it, was exploitive and hindered development when seen from the interests of the “society of nations”, or “put less rhetorically, men and women in general.” In 1917, the Stockholm conference closed and Balch returned home as the U.S. entered the war.

In 1918, Wellesley informed her that its Trustees were debating whether to renew her contract. Awaiting their decision, she continued the activism that was precisely the focus of Wellesley’s concerns, and in May 1919, while she was at the Zurich Congress of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), she had word that Wellesley had effectively fired her. So, from 1919-1922 Balch served as WILPF’s secretary in Geneva, where she organized its congresses and summer schools, and coordinated efforts to lobby the League of Nations, promote postwar reconciliation, and advance the principles of a new diplomacy.

WILPF argued that peace was inseparable from liberty: women’s rights, the protection of labor, children, and minorities, were, along with disarmament and arbitration, the heart of global comity. For Balch, feminism illuminated how hierarchy depended on latent force that denied the fundamental humanity of some people. Male dominance trained a culture of aggression and violence in men that normalized war. Her research on immigration also made her appreciate the importance of cultural diversity as a creative force for humanity; but she criticized, likewise, hyper-nationalism when it silenced that diversity and encouraged racial animosity.

Balch stepped down from the Geneva office in 1922 suffering from exhaustion. In 1926, prodded by Haitian members of the WILPF, she joined an inter-racial committee to examine the U.S. occupation there, which reported that it was an unmitigated disaster for the Haitian people. In the early 1930s, Balch represented WILPF on a League of Nations Commission sent to resolve a dispute between Liberia and the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. The experience exposed the tension in her commitment to social justice and anti-racism. Balch believed that she had to criticize Liberian elites for their corruption, yet one colleague, Anna Melissa Graves, believed that anti-colonialism required Pan-African solidarity, and WILPF’s attacks on Liberia’s governance could be used as a pretext for foreign intervention. If Balch wanted to build an “international community based on a common humanity”, she failed to reconcile this with the psychological need for a liberation politics based on race. She was aware of the paradox: white, anti-imperial feminists could not destroy the legacy of the “White Man’s Burden” by intervening on behalf of their own conception of humanity. She rejected racial science but found her position as a white reformer come up against what Frantz Fanon would later identify as the subjective necessity of asserting a substantive black identity in a racialized world.

The 1930s posed other dilemmas. Balch lobbied for the Kellogg-Briand Pact, to press the League into action against Japan in Manchuria, and to support disarmament talks. Yet she was in Europe during the rise of Nazi Germany, which forced her to affirm that anti-fascism had to take precedence over pacifism. She supported U.S. intervention in 1941, a position that made her a more attractive candidate for the Nobel Prize after the war.

In 1945, a WILPF committee, backed by John Dewey and Norman Angell, nominated Balch for the Nobel Peace prize. In 1946, at age 79, she shared the prize with John R. Mott of the YMCA. She was too ill to travel to Oslo, but made the trip in 1948, delivering her Nobel Laureate Lecture entitled, “Toward human unity, or beyond nationalism.” In her 80s, Balch still found energy to criticize McCarthy’s “cult of fear and suspicion,” to recommend rapprochement with communist China, and to insist that “peaceful coexistence” fell short of the ideals of an international community. She died in 1961, a day after her 94th birthday.

Balch’s conception of world peace was initially based on Christian fraternity and, after 1921 when she became a Quaker, a commitment to non-violence. Intellectually, she was also steeped in a Pragmatist anti-essentialism that understood identities not as fixed biological realities, but as functions of human interaction. This led to a feminism in which it was less the “motherhood” of women that made them receptive to peace than their subservience to a gendered order that diminished their full humanity. Her critique of racism was equally emancipatory: the world had to chose between ethno-racist imperialism and democracy; it could not have both. For her, the key to a planetary civilization was a radical commitment to cultural pluralism and egalitarian communication.

Suggested Readings

Addams, Jane, Emily G. Balch, and Alice Hamilton. Women at The Hague: the International Congress of Women and its results. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003 [1915].

Gwinn, Kristen E. Emily Greene Balch: the long road to internationalism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Plastas, Melinda. A band of noble women: racial politics in the women’s peace movement. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011.

Stuart Hall’s Fateful Triangle

(from Harvard University Press Blog, 25 September 2017)

The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, and Nation, new this month, is the first publication of the W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures delivered by Stuart Hall in 1994. Hall, a Jamaican-born theorist and a founding father of the field of cultural studies, said that his aim in the lectures was to update Du Bois’s formulation of the problem of the color line by viewing the question of ethnicity’s unresolved relationship to race, on the one hand, and to nation, on the other in a way that radically unsettles all three terms. “Posing the question in this way,” said Hall, “presents us with what I see as the problem of the twenty-first century—the problem of living with difference—in a manner that is not only analogous to the problem of the ‘color line’ that W. E. B Du Bois pointed to more than a hundred years ago but also a historically specific transformation of it.” As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. remarks in his Foreword to The Fateful Triangle, Hall “wanted to show both the fallacy of relying on the old categories, laced as they were with power, and the risk of courting fundamentalism in defending them, a warning that seems remarkably prophetic today.” A passage from Gates’s Foreword is below.

“What we might think of as “Hall’s Dilemma”—the challenge of keeping people from investing meaning into “race” as a category of biological difference, based on superficial differences visible to the eye—is as old as some of the earliest European encounters with “the other” in Africa and the New World in the modern period (beginning five hundred years ago), when differences of culture and phenotype soon fused with economic desire and exploitation to produce “the African” as a new and mostly negative signifier. And for centuries, this toxic compound has played into our very human instinct for defining ourselves through some of our most obvious, often “measurable” differences, such as skin color, cranial size, width of nose, and other body parts, all haphazardly gathered under the category of “race,” which itself at various times could either be an amalgam of ethnicity, religion, and nationality, or be separate from each of these.

Through what Hall described as a loose but lethal “chain of equivalences” (a concept he borrowed from the Argentinean political philosopher Ernesto Laclau) drawn between what the eyes could see and what the mind could perceive, hierarchical scaffolding of one kind or another has been erected, with those in power seizing the authority to produce knowledge about what those differences, arbitrarily elevated over others in importance, signified, and then to act on those differences, or that chain of differences, with devastating real-world consequences.

What also intrigued Hall was how oppressed groups themselves, in acts of seeming self-liberation, inverted these categories without discarding them, instead championing racial or ethnic pride as if they believed that after surviving the lethal effects of essentialization, the most efficacious way to defeat, say, anti-black or anti-brown racism or colonialism was to flip the script, embrace physical differences, and essentialize themselves. And so the boundaries of nations-within-nations were drawn, with those at the center and those on the periphery locked in a struggle over power rather than a struggle over the discursive terms expressive or reflective of that power. In other words, in a messy world of mixing and migrations, he observes, the boundaries of race, ethnicity, and nationality somehow maintained their distinctiveness—a development that not only offended Hall’s cosmopolitan sensibilities but troubled him as he searched for a better, more just, more reliable signifier of cultural difference.

Giving Hall’s quest its urgency was the fact that the world in the mid-1990s was rapidly shrinking, with one century giving way to another at a time of increasing technological change, economic interdependence, and mass migration, accompanied by a rise in fundamentalism along racial, ethnic, national, and religious lines. Hall saw pockets of hope in the creative yearnings of marginalized groups laying claim to new “identifications” and “positionalities,” and fashioning out of shared historical experience “signifiers of a new kind of ethnicized modernity, close to the cutting edge of a new iconography and a new semiotics that [was] redefining ‘the modern’ itself”—a theme Hall had explored in his seminal essay “New Ethnicities,” first delivered as a conference paper at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1988.

At the same time, however, he saw that there was cause for grave concern that the world could pull apart along the old, worn-out seams just as it had begun to come together, with rigid categories of racial, ethnic, and national differences only hardening in the face of the prospect—or threat—of meaningful change. Hall “advocated for a different, postcolonial understanding of multiculturalism,” the historian James Vernon writes. “It was one that both acknowledged and celebrated the hybrid and mongrelized nature of cultures that slavery and colonialism had both produced and displaced. Colonial history ensured that it was no longer possible to conceive of specific communities or traditions whose boundaries and identities were settled and fixed.”

Realist though Stuart Hall was when it came to the potency and indisputable resiliency of racial, ethnic, and national schemes, he did not come to Harvard in April 1994 to replay broken records. Instead, he came, as he said in his first lecture, “to complicate and unsettle” society’s persistently held notions of race, ethnicity, and nation—what he referred to in the title of the lecture series as a “fateful triangle”—and to open up new possibilities for defining our twenty-first-century selves. Not only did he teach that those old categories of difference failed to capture the blurriness of human existence, the myriad intersections of identities, pasts, and backgrounds; he also made plain that, in pretending to represent anything close to pure boundaries between groups, those old categories carried with them histories of oppression, perpetuating dangerous group-think while reinforcing hierarchical notions of cultural difference. The slate needed to be wiped clean, and Stuart was holding the eraser.

http://harvardpress.typepad.com/hup_publicity/2017/09/stuart-halls-fateful-triangle.html

____________________________________________________________________________

Trump and Obama Find Common Ground. Blame Postmodern Professors

Daniel McNeil

Associate Professor of History and Migration and Diaspora Studies at Carleton University

After the pollsters and political scientists failed to predict Trump’s victory in the Electoral College, the left-leaning journalists started looking around for someone to put their faith in. They quickly coalesced around the philosopher Richard Rorty, and began to venerate the sage who warned us about the Trump Stormtroopers poised outside the gates of our offices, courts and universities.

Rorty’s 1998 prediction that “the nonsuburban electorate” will look for a strongman who will demolish the smugness of the bureaucrats, lawyers and “postmodern professors” – and wipe out the gains made by black and brown Americans – seems to have staying power. It may even become a mantra for designed for Democrats bombarded by the group therapy, the think pieces and the panel discussions that offer columnists safe spaces to proselytize in the name of class matters, the failure of identity politics, or the ghost of liberalism.

It is not surprising that Rorty has emerged as a patron saint for members of an Obama coalition who believe that their politics is about pragmatically solving problems (as opposed to an insistence on solutions that conform to religious or metaphysical dogma or rigid moral and political agendas). His fears about an “unpatriotic academy” in an op-ed for The New York Times in 1994 were evident in those passages in Obama’s 1995 memoir that made fun of radicals flogging newspapers on the fringes of college towns, and sought to distance his mature identity against “the more politically active black students. The foreign students. The Chicanos. The Marxist professors and structural feminists and punk-rock performance poets” who discussed “Franz [sic] Fanon” at night.

One also finds Rorty’s pragmatic philosophy haunting Obama’s 2008 electoral campaign. After all, its slogan of hope was a crystallization of Rorty’s belief that American liberals needed to engage with “the unending hopelessness and misery of the young blacks in American cities,” but should not claim that “these people” must be helped because they are our fellow human beings. For Rorty (and Obama), it was much “more persuasive, morally as well as politically, to describe them as our fellow Americans – to insist that it is outrageous that an American should live without hope.”

Before spreading Rorty’s prediction in a lengthy article about Obama’s legacy in The New Yorker, David Remnick anointed Obama as “a man of integrity, dignity, and generous spirit” and wrote an extensive biography of the first African-American president that never really grappled with one of the key tensions for liberal nationalists. That is to say, Remnick’s biography managed to claim that Obama ‘‘clearly felt that the days of nationalism and charismatic racial leadership were outdated and played out” two pages after it insisted that Obama worked hard to obtain the ‘‘emotional connection that marked his performances later on.’’ Some of its anecdotes, however, provide us with raw materials to parse Obama’s pragmatic belief that charismatic leadership and sentimental appeals should be celebrated when securing a liberal future for the nation (and denounced as part of an intolerant past when used in service to local and transnational identities).

Perhaps the most revealing tale relates to Obama’s time in New York and his reflections on a course that he took with Edward Said at Columbia University. We learn that the man who would be American-in-chief was not impressed by the seminal thinker and labelled him a bit of a flake. Obama-the-student-consumer wanted to read Shakespeare rather than get bogged down in postcolonial analysis. He wanted to figure out how to sway audiences and opinion leaders rather than deconstruct what philosophers and political scientists like to consider Western civilization. He might move Churchill’s bust out of the Oval Office to make some room for Martin Luther King Jr., but he’d never forget to remind us that he thinks the British imperialist was a great guy.

Those of us who trace the source of our hopes to the struggles of diverse postcolonial peoples for democracy and liberation around the world may find it more productive – morally as well as politically – to pay more attention to the man Obama dismissed as a flake. If we do, we discover that Said is difficult to pigeonhole as a postmodern literary critic (he repeatedly critiqued what considered the jawdropping jargon of postmodernism). We also find someone unwilling to give up his critical perspective, intellectual reserve, and moral courage to find acceptance in an American public sphere. Someone who repeatedly pointed out the creative possibilities of secular humanism that drew inspiration from the wise counsel of Hugo of St. Victor, and believed that “the man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land.”

So, how might the Palestinian exile, more at home with New York’s art and culture than Obama and Trump ever will be, serve as an inspiration for those of us who wish to speak truth to power, find a way to make power listen, and smuggle new insights into commodified public spheres?

We may, perhaps, ask why the risk-averse Obamas thought it was politically possible for Michelle to talk about how she was sickened to her core by Trump’s misogyny. Put slightly differently, why haven’t the Obamas felt, or at least felt able to express in public, any sickness in response to the terrorism of the American state and the killing of unarmed people by the police or drone strikes?

We may ask how many of those Democrats angered by Trump’s bleak description of American inner cities are now willing to challenge Rorty’s vision of unending misery and pain – not creative artistry and transnational connections – for young blacks in American cities. Or how many Obama supporters are willing to acknowledge the critical differences between the speech he gave at the vigil after the Newtown, Connecticut murders at Sandy Hook Elementary School and the speech that he delivered in Chicago, Illinois at Hyde Park Academy in the wake of the murders and the lack of a trauma center for young people on the South Side of Chicago. As Christina Sharpe and others have reminded us, Obama’s refrain in Newtown was that we must do everything we can to save every American child (all American lives matter). In Chicago, his refrain was that we might not be able to save every child (you don’t become POTUS without knowing that the American media believes some lives are more grievable than others).

We have a bounden duty to interrogate a punditocracy that trots out PR releases from parties to secure access, much like film critics trot out PR releases from Hollywood companies to secure access to celebrities. We can’t continue to accept its tired rhetoric about blue collar voters when the politics and poetics of cross-racial alliances in working-class life are so self-evident, accessible and lovingly portrayed in our neighbourhoods. We can’t just accept the scripts and statecraft of Hollywood films when we have access to the everyday multiculturalism conveyed in the films of Michel Gondry in New York, Ken Loach and Mike Leigh in Britain, and the Dardenne brothers in Belgium.

We may also consider, as a final example, some recent developments in Canada. In this demi-paradise for liberals who said they would flee the United States in the event of a Trump victory, we still find plenty of folks who are willing to wall off people of colour. This isn’t usually done with the locker room talk of a Trump, but in the stentorian tones of the political scientist who uncritically talks about underdevelopment, and the passive aggression of the sociologists who only think to use the second generation immigrant to talk about so-called “visible minorities.” It is rare to find discussions of overdevelopment that may help us to work through our attachments to a North American public sphere convulsed by fear, sickness and nostalgia. It is even rarer to find a mainstream journalist using the term second-generation immigrant to describe someone racialized as white, particularly if their parents were born in the US or the UK. For all the column inches devoted to covering an “immigrant from Tanzania” who is running to lead the Conservative Party of Canada, it is difficult to find any articles that hailed David Miller, the former mayor of Toronto who was born in the US, or Tony Clement, a Canadian MP born in the UK, as immigrant candidates.

If we are serious about creating a world with a more human face, we may want to spend more time challenging the unbalanced use of phrases like underdevelopment and second-generation immigrant – whether they pass for common sense in our political debates, our media or our universities. Moreover, we may wish to heed the insights of courageous intellectuals who offered pointed reminders about the pitfalls of identity politics – particularly the identity politics of elites who surround themselves with people who look like them, sound like them and dress like them.

Daniel McNeil is Associate Professor of History and Migration and Diaspora Studies at Carleton University. His most recent book is Sex and Race in the Black Atlantic.

__________________________________________

U.S. Supreme Court declares same-sex marriage a “fundamental right.”

June 26, 2015

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled, by a 5-4 margin, that same-sex marriage is a legal right across America, and that the 14 states with bans on gay marriage (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, most of Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee and Texas) will not be able to enforce them because they violate the 14th Amendment. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, offered these words, that quickly went viral: “No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice and family. … [The challengers] ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The constitution grants them that right.” The dissenters were led by a visibly angry Justice Antonin Scalia (who was no doubt already smarting after losing the Court’s decision on the Affordable Care Act this week). He described the decision as a “threat to democracy”. The other dissenters were Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and John Roberts. A handful of Republican political hopefuls also spoke out against the decision, but for the most part the decision reflected the steady and decisive shift in national public opinion (and President Obama’s) since Massachusetts first legalized same-sex marriage in 2004. While Scalia vented that the decision was a “judicial putsch” that defied the “unanimous judgment of generations” and imposed the values of the Court’s progressives on the rest of the nation, it’s equally clear that the Court majority is more in step with the values now embraced by most Americans. Support for same-sex marriage currently stands at about 57 percent, although that number is much higher among younger Americans.

For some of today’s coverage:

Republican critics (Reuters)

________________________________________________________

A tribute to Ornette Coleman (1930-2015)

June 11, 2015

The great jazz alto-saxophonist Ornette Coleman died in New York City today at the age of 85. Born in Fort Worth, Texas in March 1930, Coleman developed his own understanding of harmony that allowed improvising musicians to play together in “unison” but in their own key. While he was initially drawn to bebop in the late 1940s, he moved to Los Angeles in 1954 and started surrounding himself with musicians whose conception of jazz was closer to his: trumpeters Don Cherry and Bobby Bradford, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins, and bassist Charlie Haden (who died last July). His first recordings came in 1958—Something Else! and Tomorrow is the question—both albums that signaled Coleman’s evident determination to push jazz in radical new directions. In the fall of 1959, his quartet played at New York’s Five Spot, in effect announcing the arrival of “free jazz” to the music world. The New York Times’ John S. Wilson described Coleman’s playing at these sets as “shrill, meandering, and pointlessly repetitious.” He subsequently revised his interpretation.

The group recorded seven albums between 1959 an 1962, including the monumental collective improvisation entitled Free Jazz in 1960. As Ian Carr has written: “His quartet had no chordal instrument—no piano or guitar—and his music was non-harmonic and not based on chord changes. His highly original compositions embodied other new factors: rhythmic accents were displaced in unexpected ways, melodic phrases often had unusual, asymmetrical lengths, and bass and drums sometimes took a much more melodic role than previously.” Although it was the radically abstract nature of the sound that caught everyone’s attention (or ire—it would come as no surprise that the album cover for Free Jazz sported a Jackson Pollock painting), Coleman’s rhythm section could swing, and his own alto phrasing was infused with blues vocalizations.

In the late 1960s, Coleman disbanded the original quartet and showed more interest in strings (Skies of America, 1962), and European classical music. By the 1980s, he had incorporated electric instruments around a band called Prime Time and even recorded the brilliantly angular Song X with guitarist Pat Metheny in 1985.

When I have introduced Coleman’s music to my U.S. cultural history class, I have done so partly to shock students into thinking about jazz differently. By the time we reach the 1960s, they will already have listened to Charles Ives, as well as the Ultra Modernists of the 1920s, so experimental music in America isn’t new to them. But they sometimes labour under misconceptions about the radical character of jazz itself and certainly don’t expect to hear the opening bars of Free Jazz. Between the mid 1950s and the late 1960s, jazz moved from bebop to cool jazz to hardbop to free jazz and the first signs of Miles Davis’ late-1960s jazz-rock fusion. Students can see the emergence of a self-consciously free style of music coming out of the more restrictive conditions of 1940s swing, and understand the connections not just to things like Abstract Expressionism and The Beats, but to African American liberation throughout the century.

This is a lot to place on Coleman’s shoulders, but musically there’s no question that even for those who never fully followed in Coleman’s precise musical path, Free Jazz opened up the idiom to waves of sonic experimentation. Even the esoteric German label ECM, widely known for its icy Nordic sound and its European melodicism, placed free music at the core of its catalogue, recording, among others, the Art Ensemble of Chicago numerous times, Dave Holland’s Conference of the Birds, Anthony Braxton and Chick Corea’s Paris Concert, Paul Motian’s Conception Vessel and Coleman alumni Blackwell, Cherry, and Haden’s Old and New Dreams. ECM’s founder Manfred Eicher once reflected on the label’s influential aesthetic:

“Paul Motian was already ‘free in the [Bill] Evans trio, changing the Philly Joe Jones approach of time into a more elastic, melodic pulse. A little later on, when I met with [Canadian pianist] Paul Bley’s music and encountered Cecil Taylor and other musicians of the so-called New York ‘October Revolution,’ it broadened my interest in all sorts of music. And it was also Scott LaFaro who showed me, in his very melodic playing, about freedom in jazz. And his dialogue in that Ornette Coleman recording of Free Jazz, with Charlie Haden—it’s wonderful, the contrast and the symbiosis. Ornette was already a catalyst for this kind of stream: His approach was lyrical no matter how burning and intensively he played. In a way, like Scott LaFaro, who was very sophisticated in his choice of notes and lines, and in his phrasing, and always, above all, melodic.”

Coleman’s obituary from the New York Times can be found here.

Andrew M. Johnston