“Buildings must evolve to meet the needs of modern times, with modern designs.”

Joanne Chianello

“We need to create buildings of our time.”

Peter Clewes

Anyone who works in the fields of architecture or heritage has heard these platitudes repeated ad nauseam. But do they really require an addition to the Château Laurier that looks so radically different from the original building?

First, it has to be said that any building built in our time is, unavoidably, a building of our time. Whatever its appearance, it will reflect the values, needs, technology and resources of the people who built it. This is nothing more than a truism; I assume that what Clewes means is that our buildings should look like buildings of our time. This could mean a lot of different things, but one thing it apparently means (to him) is that they must not resemble buildings from ‘other times’.

But what if one of the values of our time is respect for history and historical architecture? This is not merely the retreat of the feeble mind into nostalgia. The Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio venerated ancient Roman architecture and never deviated from its formal vocabulary, but still managed to design buildings of striking originality and enduring value.

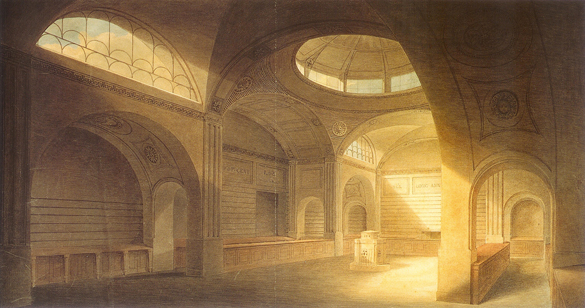

Similarly, the English architect John Soane designed in an idiom that is clearly Neoclassical. But he swallowed that style whole, made it his own, and turned it into something new that was neither a copy nor an affront.

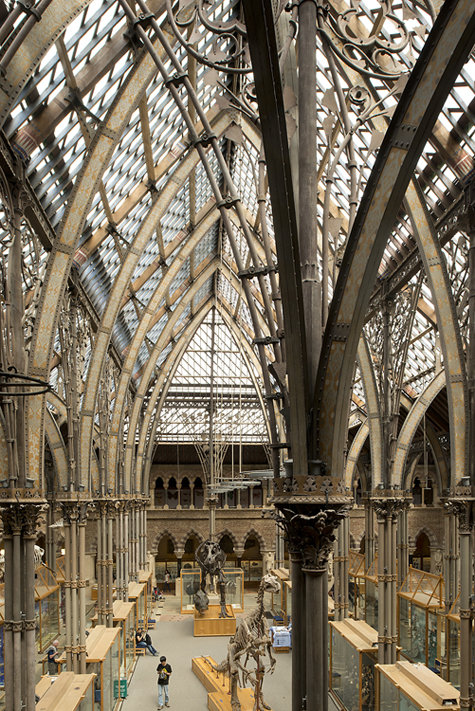

By the time Thomas Deane and Benjamin Woodward designed the Oxford Museum in the 1850s, new materials and the need for new building types (like museums) had radically transformed architecture. Their Gothic Revival building is a breathtaking re-imagining of medieval Gothic through the lens of mid 19th-century needs and technology.

So, it’s possible to employ historical styles while being original and true to one’s own time. In fact, most of the history of Western architecture is the history of re-interpreting and re-inventing past styles. The notion that being modern means rejecting the past is a very recent one. Although Chianello and Clewes state it as if it’s a timeless truth, it is in fact very much a child of its time. And that time was rather brief. It gathered steam in the 20th century, but was already getting tired by 1966, when Robert Venturi (an architect who cites Soane as one of his influences) published his Postmodernist manifesto, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.

The other argument made last week in favour of a radically Modern extension of the Château Laurier is that heritage guidelines actually require additions to be fundamentally different in style from the original building. I’ll deal with this misrepresentation of the guidelines in my next blog.

Peter Coffman

peter.coffman@carleton.ca