The establishment of international organizations provided a measure of American protection. But what about the future of Western European states? Both the First World War and the Second World War occurred in large part because of Franco-German conflicts. Creating a stable Europe required reconciliation between France and Germany.

One of the major obstacles to Franco-German reconciliation after the war was the question of coal and steel production. Coal and steel were the two most vital materials for developed nations; the backbone of a successful economy. Coal was the primary energy source in Europe, accounting for almost 70% of fuel consumption. Steel was a fundamental material for industry and to manufacture it required large amounts of coal. Both materials were also needed to create weapons.

The largest concentration of coalmines and steel production was found in two areas in Western Germany: the Ruhr Valley, and the Saarland. The Allies detached the Saarland from West Germany and made it a semi-autonomous region. In the Ruhr Valley, the Allies placed restrictions on the production, ownership and sale of coal and steel in an attempt to restrict German economic growth. The Ruhr Valley coal and steel production was also restricted as a guarantee to Germany’s neighbours, France, Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands, that these crucial resources would not be used to re-create a Germany army.

France wanted to control and access the coal and steel in the Ruhr Valley and wanted the Saarland permanently separated from West Germany. The French government was especially worried that West Germany could use its massive coal and steal resources to attack France once again. West Germans, under the leadership of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who was elected in 1949, wanted the Saarland returned to Germany and objected to the strict controls placed on Germany heavy industry. The Franco-German conflict persisted over coal and steel. A reconciliation of the two former enemies seemed unlikely.

The solution to the coal and steel problem and the core of the reconciliation between France and Germany was the Schuman Plan, named after the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman. The Schuman Plan was presented on 9 May 1950. It argued that coal and steel production should be placed under a supranational High Authority. Following shortly after Schuman’s declaration, the negotiations that established the European Coal and Steel Community began. The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) pooled the coal and steel resources of six European countries: France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (BENELUX). These countries would be collectively known as “the Six”. Pooling coal and steel resources greatly reduced the threat of war between France and West Germany. The ECSC became a reality in 1952.

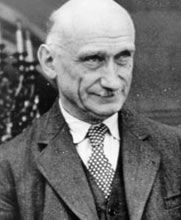

The author of the Schuman Plan was another Frenchman, Jean Monnet a bureaucrat in the French government. Monnet had worked at the League of Nations between the World Wars and was committed to the goal of a United States of Europe. Monnet was also the first President of the ECSC. For Monnet, and for Schuman, the ECSC was to be the first step in creating an federal Europe.

Click here to proceed to the European Economic Community; the next step in integration.