By Josee Beaudry, Department of Psychology, Carleton University

By Josee Beaudry, Department of Psychology, Carleton University

Christopher Mushquash is Ojibway and a member of Pays Plat First Nation, located on the north shore of Lake Superior. Among many titles, he is a clinical psychologist, Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at Lakehead University and the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, and a Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Mental Health and Addiction.

His work is very much influenced by his past experiences and who considers himself to be. He tries to use those experiences within his work as both a researcher and a clinician.

Having an Indigenous background and growing up rurally allow him to not only see some of the disparities in health but also the great strength, wisdom, and diversity in culture-based healing approaches. Cultural traditions differ from region to region and to simply force one’s own ideals onto communities is, at best, ineffective in addressing issues and, at worst, can do harm. This mindfulness led him to develop a skill set that would make him useful to people from communities like his own. In general, Mushquash looks into ways of increasing wellness. Through research he hopes to find ways to help people manage difficulties and past experiences. He also hopes to enlighten people about their approach to research and interventions in Indigenous communities.

Mental Health and Overall Wellness

Mushquash is currently addressing a number of research questions with multiple indigenous communities across the country. Some of the main areas he is focusing on include, trying to understand what mental well-being means from the perspective of the First Nations peoples. Perhaps most importantly, what steps must be taken to use that understanding to improve services and help those in need. This understanding starts by viewing mental health less through a mainstream lens and more through culturally-based one.

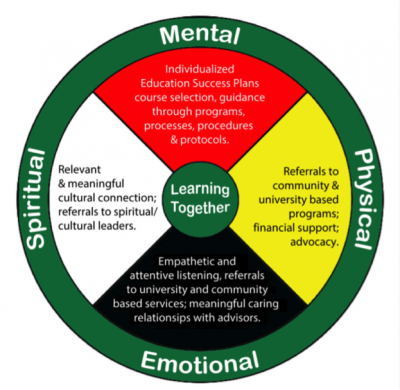

The most prominent view on well-being is a Western medical approach, often thought of as an absence of illness. Meaning, if you aren’t sick, you’re healthy. Indigenous communities view health more as a balance of various aspects of overall wellness. Depicted by the medicine wheel, an Indigenous view of health and wellness takes on a more holistic perspective.

Physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health are aspects of one’s overall well-being; there isn’t a specific focus on one or the other. Mushquash suggests that promoting wellness isn’t just about making people who are sick feel better but about nurturing people as a whole. It is this understanding of wellness that he uses to promote change in services from community to community. Communities always find approaches that work best for them. He tries to not dictate what approach they take but rather helps them find and develop their own, based on their own experiences, cultures, and contexts.

A Culture-based Approach

A Culture-based Approach

In his talk on Indigenous Youth Mental Health, Mushquash provided examples of issues that arise when applying the same standards across community to community and individually in the diagnosis. Some of the diagnostic criteria can appear to contradict each other, there are many possible combinations of symptom presentations that could lead to diagnosis, and two individuals diagnosed with the same disorder could have different symptom profiles. The truth is there are many individual, cultural, and contextual factors at play in how mental health difficulties are expressed. Misdiagnosis can occur and people may not get the help that they need.

Mushquash and his colleagues’ research on mental health and addiction show that social determinants greatly influence the prevalence and expression of disorders. Genetics, biological factors or brain neurochemicals associated with mental health difficulties are one part of the picture. But poverty, homelessness, access to services, and education also influence mental health. And for many Indigenous groups exposure to colonization practices and assimilation policies have generational and intergenerational effects on mental health. Mushquash and his colleagues try to contextualize Indigenous conceptualizations of wellness within this framework.

Mushquash gives credit to everyone he works with for the research he is a part of and the work he continues to do today. He is proud to work with a lot of great students, and is a great mentor, researcher, and clinician who promotes an Indigenous understanding of wellness. He hopes to one day see fewer misconceptions of well-being and improved health among indigenous populations.