By Stuart J. Murray, Department of English Language and Literature, Carleton University

By Stuart J. Murray, Department of English Language and Literature, Carleton University

Earlier this spring, I was asked to present my work on bioethics at the annual Ontario and Canada Research Chairs Symposium. In 7 minutes, I was to present a PechaKucha style presentation: 20 images, each displayed for 20 seconds, with my dynamic and charismatic voice-over. It was billed as an occasion to address government, industry, and community “stakeholders.”

I declined.

How could anyone repackage, in palatable sound bites, the ethical concerns plaguing Canada’s prison system, its crisis of mental health, its overuse of solitary confinement, its quiet racism, its suicides and homicides? The presentation format, which encourages chirpy advertising for applied research or “commercializable” outcomes, seems to forbid any serious discussion of an escalating crisis. Certain truths simply cannot be spoken in such a setting.

It some respects the Research Chairs Symposium is an apt metaphor for the prison system itself. Both impose a structural violence that is largely invisible, camouflaged by publicity extoling quantifiable “excellence,” statistics on economic efficiencies, and “accountability.” If we were to address these managerial abstractions on their own terms, we would be confronted with “content” that seems neither ethical nor unethical as such. But ethics is a question of form—the concrete ways that these structures affect the life of research and research into those lives (and deaths) lived within the structural confines of the prison.

Ethics is a matter of what can be said, thought, and brought to public consciousness. And yet, the terms that govern public presentation and deliberation impose a certain censorship. This is not simply to say that old-fashioned repressive measures stop people from speaking or publishing. We might call this a police function. More insidious, however, is the censoring violence that seems to come from nowhere, as if it emerged from and was recommended by the complex, anonymous system itself. By invisible hands.

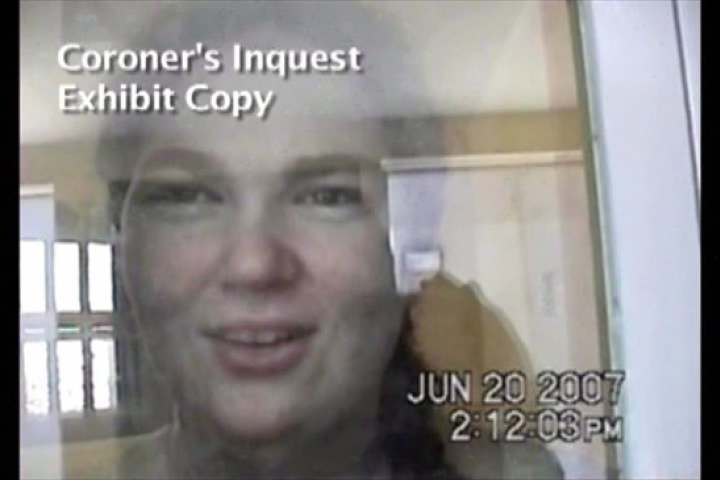

Ashley Smith image taken from a coroner’s video. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO

As an example, we might consider Ashley Smith’s treatment at the hands of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). On 19 October 2007, Smith, a mentally ill nineteen-year-old inmate on suicide watch, tied a ligature around her neck and strangled herself to death while in the care and custody of the CSC. Correctional officers watched and filmed the event from outside her cell (the policy in Canada is to video-record all strip searches and “use of force” incidents). Three front-line staff and one correctional manager were initially charged with criminal negligence causing death, but these charges were soon dropped; prison staff were merely following the warden’s orders not to enter the cell “if she’s still breathing.” Effectively, nobody was responsible for this death, even after the jury in the $5 million coroner’s inquest declared her death a homicide: death at the hands of an anonymous system, as it were.

During her final year of custody, spent almost entirely in solitary confinement, Smith was transferred 17 times between 9 different institutions across 5 provinces. Each transfer re-set the clock on her seclusion, sidestepping legal limits for the length of time it can be used. Several video-recordings depict Smith being forcibly restrained by multiple correctional officers (or were they healthcare providers?) outfitted in full riot gear; another video depicts one of Smith’s extralegal transfers between facilities, hooded and being duct-taped into the seat of an airplane, pleading with her captors. Mental illness in the guise of terrorism, calling for counter-insurgency measures, it would seem. In this light, the system must be understood as remarkably coordinated across and between correctional facilities—a structural violence if ever there was one. Staff were instructed to lie and falsify reports about Smith in order to give the illusion that efficiency and accountability prevailed in their institutions. In terms of mental health care, of course, this is a picture of utter inefficiency and unaccountability, with no apparent justification other than cruelty and violence themselves.

The censorship of repressive police functions often operates hand-in-hand with a structural violence that is more furtive because it is invisible, anonymous, systemic, and complex. The gears and mechanisms of these structures are further eclipsed by the celebratory din of managerial efficiency, accountability, and excellence. The spectacle is essentially empty, but it represents the new face of our public research universities, “colonized,” as Willem Halffman and Hans Radder have recently argued, by a “mercenary army of professional administrators, armed with spreadsheets, output indicators and audit procedures, loudly accompanied by the Efficiency and Excellence March.” Meanwhile, government and media-sponsored discourses on security and risk—PechaKutcha style—serve to justify in moralizing sound bites the police function, and shore up the structures meant to ensure public security and mitigate risk. Public research funds are hijacked by government, redirected to business “partnerships,” ushering in a new “dark age” for Canadian science. The new fundamentalism silences scientific evidence.

The strategy is not working, although it may win votes. According to the Office of the Correctional Investigator, Canada’s prisons are sites of racialization and hyperincarceration of people of colour, notably for Black and Aboriginal populations. Public Safety Canada reports in particular that the number of incarcerated Aboriginal (self-identified Inuit, Innu, Métis and North American Indian) persons is disproportionately high: 33.0% of incarcerated women, 22.6% of men, while Aboriginal adults represent barely 3.0% of the Canadian population—an over-representation that far exceeds the per capita over-representation of African-Americans in the U.S. prison system.

31% of offenders in segregation units self-identify as Aboriginal. However, these statistics only represent federal institutions, not provincial ones. They do not include the many institutions that run segregation facilities known euphemistically as “alternative housing arrangements, secure living environments, special needs units, mental health units, intensive support units or gang ranges.” The government report flippantly refers to these as “Segregation ‘Lite’.” These provincial units operate outside of administrative segregation law, and therefore, according to the Correctional Investigator, “do not have [the] appropriate level of procedural safeguards/oversight.” Despite what our prime minister says, these are sociological problems.

31% of offenders in segregation units self-identify as Aboriginal. However, these statistics only represent federal institutions, not provincial ones. They do not include the many institutions that run segregation facilities known euphemistically as “alternative housing arrangements, secure living environments, special needs units, mental health units, intensive support units or gang ranges.” The government report flippantly refers to these as “Segregation ‘Lite’.” These provincial units operate outside of administrative segregation law, and therefore, according to the Correctional Investigator, “do not have [the] appropriate level of procedural safeguards/oversight.” Despite what our prime minister says, these are sociological problems.

How do we come to terms with these numbers and the concrete lives they represent? And what is our responsibility, as a society, in the care of those who are imprisoned and, increasingly, diagnosed with a mental illness? Structural violence is social violence. If we think that ethics is limited to what it is right or wrong to do, this remains far too abstract unless we can account for the structural conditions under which something will appear for us as right or wrong—as well as the terms in and by which we think these thoughts, communicate them, and deliberate them publicly.

Language is not a neutral structure in this regard; it is not simply a tool, but rather actively structures our relations with others. One essential task of ethics is to intervene into the structural conditions to make these truths speakable, to bring them to public consciousness, and to foster critical dialogue. In other words, it is an ethical injunction to create conditions for public discourse, and to expose the invisible hands that manipulate in advance what truths can be spoken, when, where, and to whom.

Forthcoming in APORIA: The Nursing Journal

Based on

Murray, S.J., & D. Holmes (forthcoming). Seclusive space: Crisis, confinement, and behavior modification in Canadian forensic psychiatry settings. In Extreme Punishment: Comparative Studies in Detention, Incarceration, and Solitary Confinement. Eds. K. Reiter & A. Koenig (Palgrave-Macmillan).

Murray, S.J., & D. Holmes (2014). “A New Form of Homicide in Canada’s Prisons: The Case of Ashley Smith,” truth-out.org (10 March).

Holmes, D., & S.J. Murray (2014). Censoring violence: Censorship and critical research in forensic psychiatry. In Power and the Psychiatric Apparatus: Repression, Transformation and Assistance. Eds. D. Holmes, J.-D. Jacob, & A. Perron (Ashgate Publishing), 35–45.

Top Image courtesy of Stuart Miles at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Bottom Image courtesy of Naypong at FreeDigitalPhotos.net