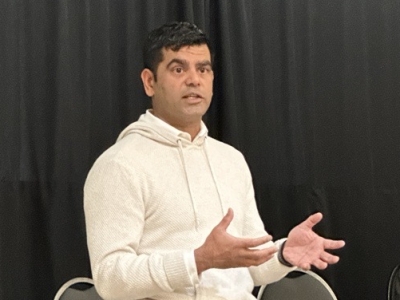

Assistant Professor, School of Journalism and Communication

Benjamin Woo is a lifelong aficionado of geek culture.

The evidence resides on his office shelf: a graphic novel by Joe Sacco, a figurine from the manga series Attack on Titan, a tin lunchbox featuring Mike Allred’s Madman, and a Zapp Brannigan ray gun. Then there’s his collection of Dungeons & Dragons manuals, left over from a recent gaming session with like-minded professors.

These days, Woo approaches geek culture with a discriminating eye. He’s published several articles on the subject and is currently completing a book manuscript based on his ethnographic research in an urban geek culture scene.

What is “geek culture”?

The words “geek” and “nerd” have been used to describe uncool, unpopular people since the 1950s, though neither really took off as common usage until the 1980s—think of Revenge of the Nerds, which came out in 1984. Today, when we talk about geek culture, we usually mean the combination of certain media (science fiction, fantasy and other cult genres, comic books, games, and so on) and certain audience practices (collecting, making fan fiction or fan art, distinctive kinds of connoisseurship).

You say that geek culture has become big business. What do we know about the industry?

Some of the most profitable franchises in the entertainment industries today come from geek culture, just look at the lineup at the movie theatre any given weekend. But, for many people, this is most obvious when their city hosts a comic convention, like the Ottawa Comiccon or Ottawa Geek Market. The best-known one is, of course, San Diego’s Comic-Con International, but regional cons like Toronto’s Fan Expo Canada and the Calgary Expo have really taken off in the last few years. Recent industry research estimates fan conventions in North America do $600 million annually in ticket sales alone and have a total economic footprint in the billions.

On the local level, you talk about the significance of comic book stores. Why are they so important?

Practically speaking, they are where overlapping media audiences gather to purchase goods. But they’re also a space where community-making happens. We hear a lot about how modern society—and modern media in particular—isolate us from one another, but I’ve spent enough time in comic shops to know that isn’t true. They are sites of interaction and communication as much as shopping.

In other words, it’s a perfect place to ask some of communication studies’ basic questions: How are people relating to one another? How do communication media—as technologies, industries, and practices—structure those relationships?

The study of comics and graphic novels is exploding in universities across Canada and the US, mostly in English departments. As a communication scholar, how does your approach differ?

Rather than thinking about comics as a form of literature, I think about it as a medium, and that means not only looking at the comics themselves but also at how they are produced and consumed. My current research is on creative work in English-language comics production. The makeup of the workforce and the conditions under which they work influence the kind of comics that are available. They are generally young freelancers, about three-quarters of them men. Despite low wages, comics creators describe themselves as very satisfied with their work situations – in part because they are overwhelmingly comics fans.

What’s next for your research?

Right now, I’m continuing to interview comics creators about their work experiences and working practices. I’m interested in what “creativity” means to commercial, rather than fine, artists. I’m also working with Bart Beaty and Nick Sousanis at the University of Calgary on a new project called “What Were Comics?” We’re doing a content analysis of the entire history of American comic books, tracking a whole host of material and formal variables, from page length to panel density, from layouts to advertising. We want to re-write the history of American comics from the perspective of the industry’s typical output, rather than focusing on individual, great works.

Friday, September 9, 2016 in Communication and Media Studies, FPA Voices, Media, People

Share: Twitter, Facebook