By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Justin Tang

When Manuel Báez first visited the small stone-covered plaza on the Ottawa side of the Portage Bridge that links the capital to Gatineau, the Carleton Architecture professor was struck by the panoramic view of the Ottawa River, Victoria Island, the parliamentary precinct, the curves of the Douglas Cardinal-designed Museum of History, and the Confederation Loop trail that connects the waterfronts of the two cities.

“My god, what a spot,” he thought. “In a way, this place is Canada.”

Báez was at the base of the bridge to refine the concept he planned to submit to the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Art in the Capital competition, which called for an artwork with a “dream” theme to be displayed at the site for a year as part of the country’s sesquicentennial celebrations.

Carleton Architecture Prof. Manuel Báez

His idea, “The Gather-Ring,” a breathtakingly beautiful wood, metal and glass installation that was erected in late August, was inspired by a pair of iconic symbols deeply rooted in Indigenous culture: the tree and the dream catcher.

With benches made from eastern white pine logs recovered from the Ottawa River and Douglas fir columns from British Columbia, built in collaboration with glass artist Charlynne Lafontaine and a multicultural crew of Architecture students, and welcomed onto unceded Algonquin territory by members of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, “The Gather-Ring” makes a powerful statement about historical perspective, cross-cultural connections and the circles and cycles of life.

“It’s an offering to the entire community,” says Báez, an artist, designer and architect licensed in New York whose work is heavily influenced by natural systems and processes, an ethos that resonates with Indigenous worldviews.

“When you sit on one of the benches, you’re being asked, in a way, to think about what was here before 1867. It’s a place to get together and talk and reflect on the past — and on the present and future.”

“Canada 150 is the perfect time to celebrate our country’s extraordinary artists and creators,” Canadian Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly said in a news release after the artwork was finished in late summer. “As we celebrate this exciting milestone, public art exhibits like these provide visitors of all ages with an opportunity to discover these beautiful pieces and open their eyes to new ideas and perspectives. I invite local residents and visitors to come and experience this remarkable work.”

Like Throwing Pebbles into a Pond

Before the Art in the Capital program was announced, Báez was already thinking about gathering circles.

Last year, his ceiling installation “Light Keeper,” created in consultation with Cardinal and Carleton students, was unveiled at Carleton’s Ojigkwanong Centre, a home away from home for Indigenous students that was designed by Cardinal. That eventually led to a partnership with the Royal Architecture Institute of Canada’s Indigenous Task Force and Ottawa’s Gignul Non-Profit Housing Corporation to create, through a summer studio course, places for people to gather in the backyards of a pair of the non-profit’s properties in Vanier.

Although those projects will come to fruition next summer — “the gathering circles are spreading,” says Báez, “like throwing pebbles into a pond” — the Portage Bridge installation has been his main focus over the last few months.

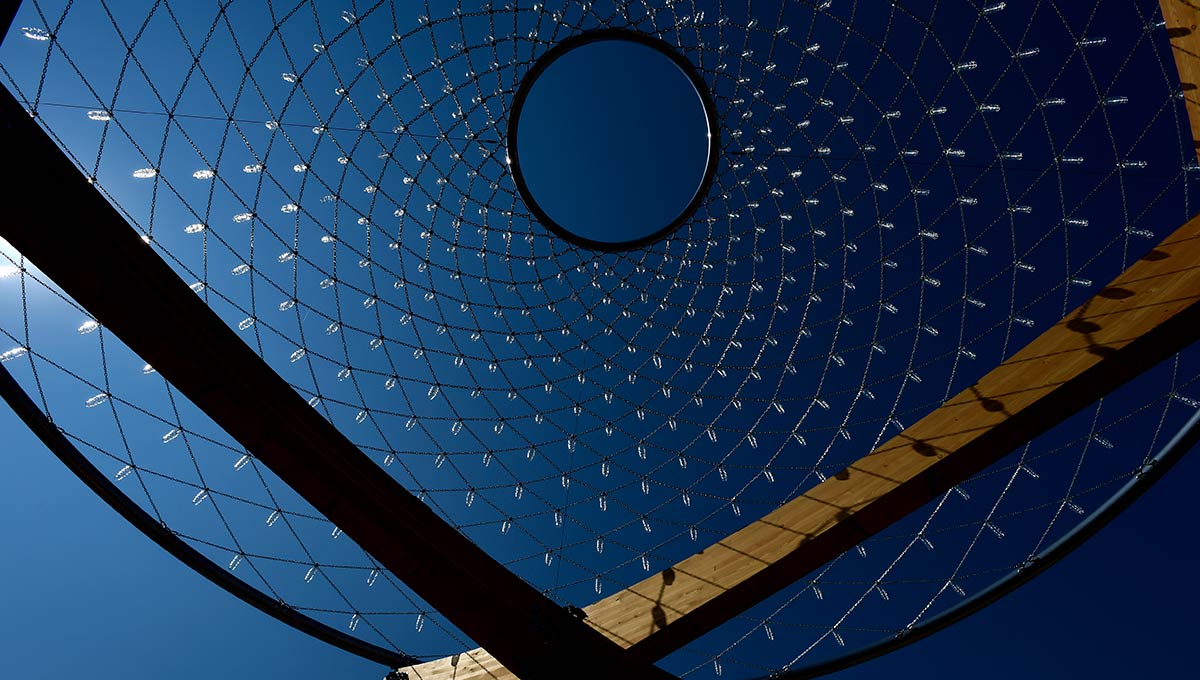

The interactive public artwork is built atop a circular red cedar base with a 20-foot diameter; students from Báez’s summer studio course burned marks onto the boards to simulate tree rings. A polished black Canadian granite circle in the middle of the base is etched with the 13-segment pattern of a turtle shell, a reference to Turtle Island, the name that some First Nations, including the Algonquin, have for North America.

A polished black Canadian granite circle in the middle of the base is etched with the 13-segment pattern of a turtle shell, a reference to Turtle Island.

Four ten-and-a-half-foot-tall Douglas fir columns, referencing the four cardinal directions and 1867’s four founding provinces, rise from the cedar and support four laminated canoe- or longboat-shaped beams. These beams in turn support the dream catcher’s cylindrical metal outer ring. (The generous support of Tim Priddle from Manotick’s The WoodSource made the project possible, says Báez).

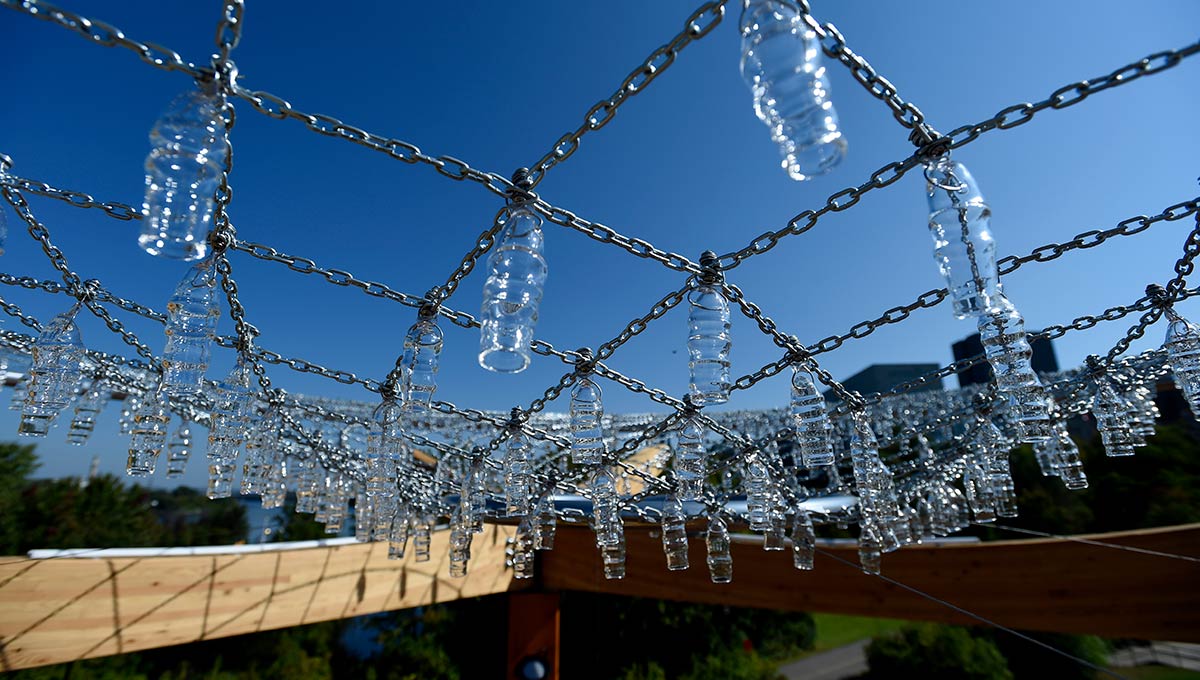

A woven galvanized chain link web hangs from the metal ring, and 598 glass pendants hand-blown by Lafontaine dangle from the web. These glass pieces catch the light in different ways as the sun rises and falls and as the seasons change, and at night they are illuminated from beneath by LED strip lights, whose colours and sequences will be programmed by Carleton engineering students as part of a collaboration led by Discovery Centre Director Alan Steele and Department of Systems and Computer Engineering Instructor, Cheryl Schramm.

“We always talk about multidisciplinary work,” says Schramm. “It’s such a thrill to be doing this. This is the type of project I want my students to experience. It’s public, it’s creative and it brings an element of Indigenous culture to an engineering class.

“Professional engineers are servants of the public,” she adds, “and this provides a way to talk about Indigenous issues and reconciliation with our students. It feels very real.”

Gather-Ring: Bringing Texture and Life to a Concrete City

Verna McGregor, a cultural helper from Kitigan Zibi, first saw The Gather-Ring when Báez was assembling it in a studio at Ottawa’s Makerspace North in early summer. She liked the dream catcher and tree symbolism, as well as the turtle and four cardinal directions. But her appreciation soared when she saw the finished artwork beside the Portage Bridge.

“It really captures your eye and is in a prominent location,” says McGregor. “Also, that area is mostly concrete, and then you see the colour and texture of the wood, which brings some life to a pretty grey place.”

The stone-covered plaza on the Ottawa side of the Portage Bridge where The Gathe-Ring is installed.

When Claudette Commanda, an Algonquin knowledge keeper from Kitigan Zibi who consulted with Báez alongside McGregor, first saw the artwork, she felt a “profound and overwhelming sense of peaceful energy.”

Sitting on one of the benches and looking up at the dream catcher will give people a moment of solace, says Commanda, and a chance to reflect or meditate — “or just to sit and be at peace with oneself and with nature.”

Like McGregor, Commanda believes the artwork is in a perfect location. Its exposure to streams of pedestrian, cyclist and vehicular traffic is an opportunity to raise awareness and educate passersby about Ottawa being on unceded Algonquin land.

A cab driver who was taking her across the river to Gatineau recently pointed out The Gathe-Ring and said, “It should stay there forever.”

The Gather-Ring also provides an opportunity for people to come together for conversation and conflict resolution, says McGregor. “When you’re sitting on one of the benches and look up, you see the spider web of the dream catcher, and the message is that we’re all connected to one another, whether we like it or not — and we’re all connected to the universe too.”

That latter idea, our essential relationship with the natural world, is crucial to McGregor. “There needs to be an awakening,” she says. “We need more dialogue to help us bridge issues of racism and violence so that all people from all nations can reconcile and work together to deal with climate change.”

Connections Between Cultures

Connections between cultures have always interested Báez, who was born in an ethnically mixed family in the Dominican Republic, moved to New York City as a child and came to Canada when he joined Carleton in 2001. “This is what motivates my work,” he says.

Báez’s birch plywood ceiling installation “Resonant Currents” at the co-working space HUB Ottawa’s former location included elements of Indigenous art, Arabic calligraphy and Celtic imagery. Ultimately, it embodied Canada’s cultural mosaic — as do the Carleton students who helped him create both it and “The Gather-Ring.”

Under a blazing sun on a hot August afternoon, Sami Karimi (who is from Afghanistan), Guillermo Bourget Morales (who is from Mexico) and Josh Eckert (a multi-generational Canadian) were hanging glass pieces from the dream catcher’s web.

Carleton Architecture Prof. Manuel Báez helps fasten 598 glass pendants from a woven galvanized chain link web.

“Experiential learning is different than learning from lectures,” said Karimi. “It’s fun to learn by doing, and it allows us to make observations and reflections throughout the process. This project was also a great opportunity for me to work with Indigenous communities and learn about their culture.”

“We’re gaining transferrable real-world skills,” said Bourget Morales.

“This project allowed us to work on a much larger scale than the models we usually work on at school. It was an amazing summer, a great experience working with the team and helping to transform Manuel’s idea into reality.”

“I can’t wait to see it finished and lit up at night,” said Karimi. “I can’t wait to see how people react.”

The Gather-Ring would not have been possible without contributions from students who were part of the Gathering Circles summer studio: Sally El Sayed, Sophie Ganan Gavela, Argel Javier, Cheshta Lalit, Lesley Li, Danica Mitric, Sepideh Rajabzadeh, Raumporn Ridthiprasart, Catherine Sole, Tharmina Srikantharajah and Wendy Yuan.

Additional contributions from: Hamid Aghashahi, Erin Allen, Jonathan Caron, Andrew Cornthwaite, Rafael Fantacci, Sara Farokhi, Frangiscos Hinoporos, Eingy Hussein, Michael Jaimeson, Gregorious Erico Kwa, Cole Peters, Ramon Renderos, Robert Shaheen, Antoinette Tang, Oliver Tang, Yoyo Cheuk Tang and Laura Yongmin Ye.

Monday, October 2, 2017 in Engineering, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook