By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

When Summer-Harmony Twenish walked into the Carleton University Art Gallery last winter to join a group of students who were starting to build a birchbark canoe using traditional materials and methods, she was flooded with childhood memories of her late grandmother who had taught her how to scale fish and skin hides.

“It was like stepping into my grandmother’s bathroom,” said Twenish, who is from the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation about two hours north of Ottawa, recalling how her grandmother used to soak birchbark in the bathtub. “The materials around me in the gallery were like little pieces of home.”

Wood shavings fall to the ground as part of the traditional methods used to build the canoe.

For three months, Twenish, a second-year Art History student minoring in Indigenous Studies, worked on the wigwàs chimam with 11 other Carleton students under the guidance of Daniel “Pinock” Smith, an internationally-renowned Algonquin craftsman from Kitigan Zibi.

The result of their handiwork — a beautiful eight-foot-long canoe held together by cedar strips, spruce roots and spruce gum — was unveiled on Sept. 28 at its new permanent home just inside the main doors of the MacOdrum Library, one of the busiest entranceways on campus with about a million and a half people using the building each year.

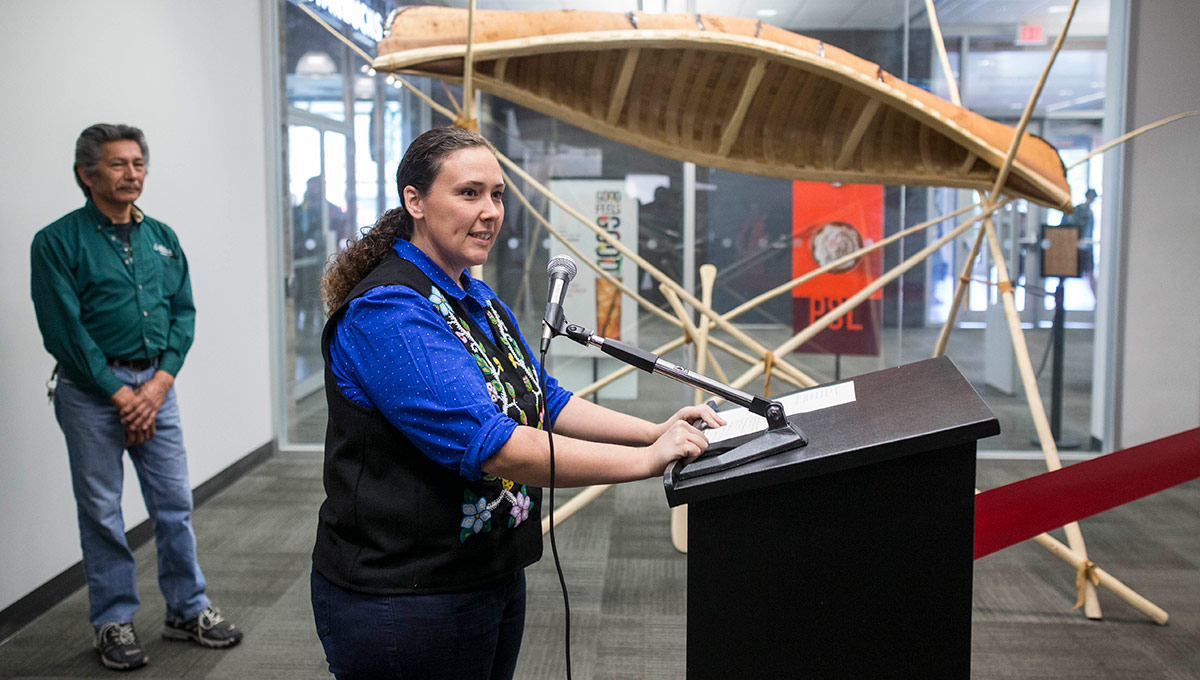

Participating in the project was both a personal healing journey and a way to create community for Twenish, who spoke at the unveiling ceremony. But even though the canoe is now finished and on display — an affirmation that there is a place for Indigenous students in an institution that stands on unceded Algonquin territory — it’s a reminder of how much work remains ahead on the path to reconciliation.

“Carleton has a duty to create space for Indigenous students,” said Twenish.

“This canoe is a symbol of the ongoing reciprocal relationship between the university and Indigenous communities.”

Learning, Accountability and Responsibility

The birchbark canoe project was organized by Carleton’s Centre for Indigenous Initiatives (formerly the Centre for Aboriginal Culture and Education) and the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) to help mark the university’s 75th anniversary.

CUAG Director Sandra Dyck opened the event at the MacOdrum Library by calling the collaboration part of “an evolving process of learning, accountability and responsibility.”

Benny Michaud, an Indigenous Liaison Officer with the Centre for Indigenous Initiatives who recruited the Indigenous and non-Indigenous students who joined the project, noted that the canoe is a “very powerful symbol of sovereignty.”

Benny Michaud, Indigenous Liaison Officer with the Centre for Indigenous Initiatives, speaks at the unveiling of the canoe.

“Some may think of Indigenous cultures as being part of a distant past with no contemporary presence,” she had said when the project was just starting.

“But our cultures are alive. These types of projects demonstrate the resilience we have, and our intrinsic and intimate relationship with the land.”

While we hear the term “reconciliation” a lot these days, Michaud added, projects like this one “create opportunities to come together and open our hearts and listen to each other.”

Gabby Richichi-Fried, one of the non-Indigenous students who helped build the canoe, noted that her participation in the project as a “settler and uninvited guest” on Algonquin land is inherently contentious because many Indigenous youth don’t have an opportunity to get involved in traditional learning.

“My fragile white city hands are blistered and splintered,” she said, grateful for the opportunity to have participated in a relationship-building experience that centralizes Indigenous knowledge in the academy. “Reconciliation is as hard, messy and uncomfortable as building a canoe from scratch.”

Sharing Laughter, Labour and Dialogue on the Path to Reconciliation

From the boiling of sap to make spruce gum to the carving of paddles and a successful water test at a Kitigan Zibi lake in mid-September, the canoe project participants shared laughter, labour and dialogue.

“It’s not really making the canoe that’s important,” Pinock told the group. “It’s learning how to communicate with each other.”

To Carleton’s Interim Provost and Vice-President (Academic), Jerry Tomberlin, this teamwork and camaraderie is an excellent example of experiential learning. “Maybe we should all get our hands dirty and make a canoe,” he said.

President Alastair Summerlee

President Alastair Summerlee, whose predecessor Roseann O’Reilly Runte was a major supporter of the project, said the canoe is more than a testament to the 12 remarkable students who built it.

“It’s the beginning of a journey in which we as a community have to work better together and learn from each other — to share our stories, our successes, our failures and our abilities to be more than the sum of our parts,” he said.

“For me, this is a very public declaration that the university will do more and better in terms of relating to, working with and, most importantly, listening to and responding to the voices of the people of the Indigenous community and communities in and around Carleton.

“Metaphorically,” he added, “I’m going be taking a trip in the canoe over the next several months as we try to find a way to work together more effectively. This canoe is a wonderful and enduring symbol of that commitment.”

New Murals at Ojigkwanong

Two hours after the canoe event, a trio of new murals and a ceiling installation were formally unveiled at the Ojigkwanong Centre, a home away from home for Indigenous students in Paterson Hall.

The ceremony was opened by Haida Elder John Kelly, an adjunct research professor in Carleton’s School of Journalism and Communication, who smudged the paintings with sweetgrass.

Created over the summer by three artists representing a range of Indigenous roots — Métis/Cree Jaime Koebel, Anishinabeg/Haudenausanee Simon Brascoupé and Nunatsiavut Inuit Heather Campbell — the murals include a cross-section of abstract natural imagery: a Manitoba crocus, the first flower to bloom in spring; an aerial view of land and water; northern lights; moose; deer; jellyfish; sea urchins; and more.

Indigenous Liaison Officer Irvin Hill with the Centre for Indigenous Initiatives, speaks at Ojigkwanong.

“It came together through a very organic process,” said Koebel, an Indigenous programs and outreach educator at the National Gallery of Canada and a Carleton alumna.

“We wanted people to look at the paintings and figure out for themselves what they represent.”

Each artist worked on each of the three canvases, using buckets of water and mops for paintbrushes to create a flowing look. Serendipity played a role, too — a water spill formed the shape of Sedna, the Inuit sea goddess, and raccoon tracks are visible where one of the critters scampered across a panel as it lay on the ground to dry.

Although Campbell knows Koebel and Brascoupé well, she had no idea how their collaboration would turn out.

“It’s like when your best friends say: ‘Let’s move in together,’” said Campbell. “You never know how it’s going to go.”

Unveiling Light Keeper

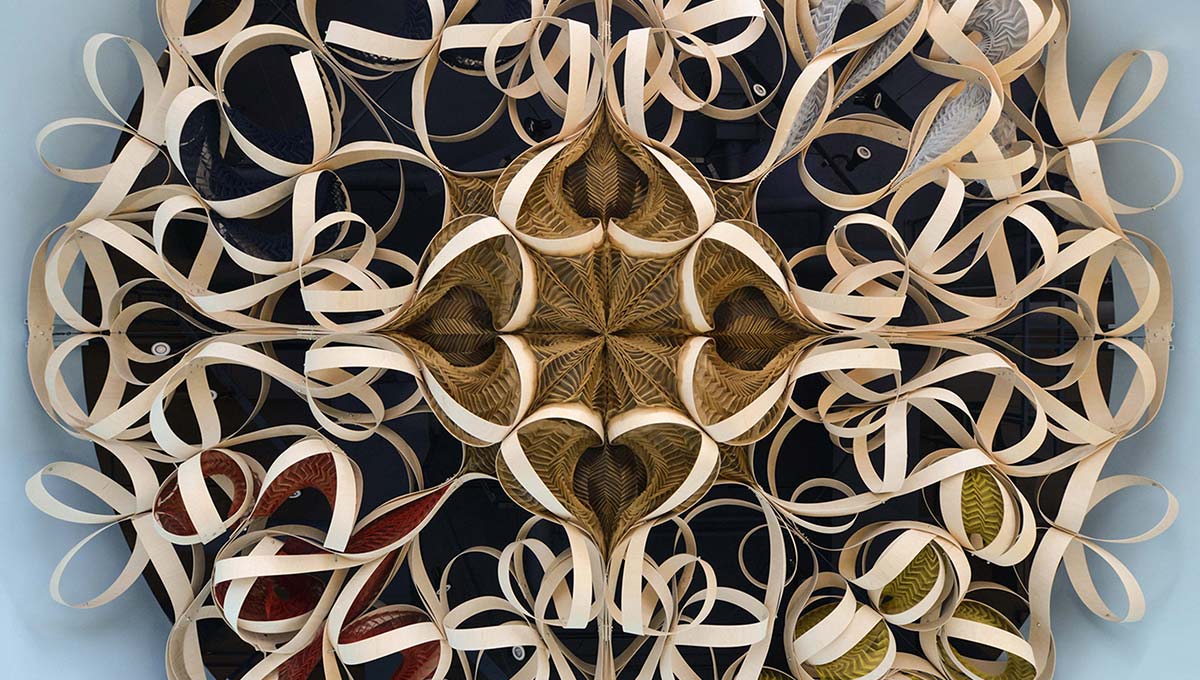

The results, however, are striking and beautiful, as is the ceiling installation “Light Keeper,” created by Carleton Architecture Prof. Manuel Báez in consultation with Ojigkwanong designer Douglas Cardinal and a multicultural group of students.

Although it was installed last year, “Light Keeper” was officially unveiled on Sept. 28. Báez, an artist, designer and licensed architect in New York, explained how he cut five-foot by five-foot birch plywood panels intro strips and bolted each strip into a malleable circle, allowing him and the students to fashion them into a whirl of braded shapes that represent the fluidity of air, water and fire.

Light Keeper adorns the ceiling at Ojigkwanong.

Above the ceremonial section of Ojigkwanong, where the new murals are displayed on a curved wall, Báez’s installation is organized and orderly, with a glowing sun-like light shining through from the ceiling. This “morning star,” like the artwork itself, is a tribute to the late Anishinabe elder William Commanda, in whose honour the Ojigkwanong Centre is named.

Beyond this space, the birch strips look more turbulent — a metaphor for the natural systems and processes that influence Báez’s work, and for the non-linear path toward reconciliation upon which we all tread.

Friday, September 29, 2017 in Community, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook