by Fatema Motiwala

My Community Origins

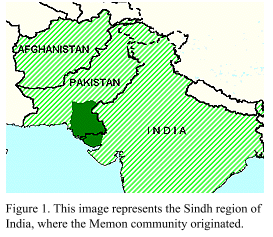

When asked that standard question, “Where are you from?” I usually reply, “Oh, I am from an Indian background. I keep it short and sweet. Of course, “Indian” is too general a term to be meaningful. It is a referent to and shorthand for what is actually a people that are from hundreds of different milieus: cultural, linguistic, religious, geographic and other features make “Indian” a sweeping generalization. One of which includes my own community, the ‘Memon’ community: we are an ethnic group that originated from lower Sindh, India.

It was early in the 15th century that 700 families, belonging to the Lohana caste of Hindus, accepted Islam and founded my community. With this conversion came the change of a different lifestyle than those of their forefathers, and the converts came to be known as ‘Memons.’ They created a native language for themselves, known as Kutchi, and integrated with the culture of new lands. Being traders during British colonial rule, Memons migrated to various parts of India, primarily to Gujarat where I was born. Memons have been called the “sailor businessmen of India (Sait, 2014)” who dispersed from Sindh and Gujarat, settling and opening businesses in various Indian cities and faraway regions in the Middle East, Asia and Africa. Memons are scattered throughout Africa, though primarily within South Africa, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania where the Kutchi language is spoken, and the Memon community is strong.

Being Institutionally Visible and Socially Invisible

My mother tongue is an Indo-Aryan language called Kutchi. For decades, Memon businesses kept their records and documents in the Gujarati script since Kutchi is an unwritten language and can only be learned and communicated orally. For Memons in Pakistan, they write Kutchi in the Urdu script since many have adopted Urdu as their dominant tongue and have no way of physically writing out the Kutchi dialect. Although Kutchi is the historical language of my community, the use of our language is sharply declining because there are fewer people that can speak it each generation. That I speak this language is surprising to community elders I meet. As it happens, Memons my age are not particularly bothered about learning the language, from what I have observed to date. They were also not taught to speak at home. The dominant language of the place in which Memons settle, whether the language is Urdu, Hindi, Gujarati, English, or Afrikaans, tends to replace Kutchi.

Language is a way by which people can identify whether a stranger belongs to their community. Speakers of a language can “hear” whether their interlocutor is a native speaker. I believe it is an integral part of our social heritage through which to express ourselves and be understood fully. There is a relationship between language and social order that can be understood through linking the value of language to the value of the resources that matter in society, including economic and political orders and historical events (Heller & McElhinny, 2017). Anthropologist Shahram Khosravi (2011) discusses a ‘double absence’ about his identity in this way,

…clearly in my linguistic impotence. I lack some domain vocabularies. For instance, I do not know the names of many flowers, trees, vegetables, insects and fishes in any language, neither in Farsi nor in Swedish or English. I never learned them in Iran or have forgotten them after my long absence. And in other languages, simply stated, I have never reached that point of fluency (Khosravi, 89).

This demonstrates how the application of linguistics directly reflects one’s own understanding of who they are and where they do or do not belong, whilst symbolizing togetherness and representing powerful ethnic sentiments. Alongside having deep socio-cultural ties, language is intrinsically intertwined with our “paper” visibility which consists of the documentation that allows us to navigate this world; as it is a question that arises on all formal documents and binds an individual to the country they choose to immerse themselves into. Khosravi shares in his writing, upon returning to the border of Sweden, the border required him to live up to his passport. While others pass through, he is “asked some ‘innocent’ questions to prove that he does speak Swedish, that he can identify himself with his passport (Khosravi, 2011).” The idea is that language stimulates belonging in personal and social ways.

Is Kutchi Approaching its Expiration Date?

Without having an official script and therefore, the ability to officially exist, that is to say on paper, I am concerned that the expiration date of Kutchi is soon to come. It is not recognized locally let alone at a state level; never will I be asked to fill out forms or answer questions at the border in Kutchi. It has been suggested that Kutchi is not a language, but rather a “Boli”. This is a Hindi term relegating it to a dialect, which is meant to convey its lower status to a language.

I am not the only one who harbours this concern. Around the world, Memons are expressing their thoughts through informal literature, blog-posts and social media. They want to be heard expressing concerns about their language. One of these advocates is Thaplawala, a blogger. We have to build an interest of Kutchi into new generations. This feeling of pride can only arise if they know Kutchi as a full-fledged language and not simply a Boli. To preserve our identity as a distinct community, we should explore the possibilities of evolving this Boli into a language. Thaplawala writes, “The Saraiki and Hindko speaking people of Pakistan have started to make efforts to preserve their identity by recently turning their Boli into written languages. If so, why can’t we do the same?”

There is solace in realizing that people are advocating for the preservation of our language, and through it, our community. How we speak, the words we choose to use: there are our connections to each other. Her concern of the language disintegration reminds me of the ‘politics of silence’ in anthropologist Victoria Bernal’s research in Eritrea. She discusses experiences that go unspoken and so unheard. The Internet became a way for people to communicate, and Bernal explains, “part of what draws readers and posters to community websites is the sense of communicating with others who know the shared losses and the absent presences” (Bernal, 29).” Drawing from her ideas, I compare my feelings of loss and the ‘shared losses’ of my community people. Will our language continue to exist as time goes on? I am persistently concerned that our language will, actually, disappear. I wonder what I might do about this.

Reflecting on the Implications of “Low Remembering”

Language is one of the cornerstones of any culture. Based on personal experiences, and also exploring the literature on the social purposes of language, language provides us with a social context for people to relate to each other in the ways that they learned from their earliest days. For minority groups, the threat to our cultures presented by the intrusion of outside influences may mean sustaining losses of various sorts. Loss of language undermines social structures and aids the disappearance of group culture, especially where the language is solely dependant on an oral history. As Lorena Anton sums up, “low-remembering often leads to generalized oblivion. In time, even the very idea of a forgotten past is eventually ‘unremembered’. Thus, forgetting the forgotten is the final stage in putting a difficult past aside forever.” Reaching that final stage of being forgotten is what I want the Memon community to avoid, the stories of who we are and where we come from must continue to thrive through our language.

As a solution, Thaplawala suggests that since the Roman script is easy and convenient for writing and communicating, we can possibly use it to write Kutchi. By formulating simple rules and assigning phonetic sounds to letters, we can create a computerized script for Kutchi and this would allow us to send emails to family and friends in our own language. He asks, “Why can’t we think about an adoption of the Roman script for Kutchi? Turkey has done this in the recent past, as well as Indonesia and Malaysia who have adopted Roman scripts for their languages. If we do this, it will be equally readable by Memons living anywhere in the world.”

Converting Kutchi to a written language has not appealed to state leaders in the past. Memons are a minority population in India. We are less than two million people worldwide. If nothing can be done about the preservation of Kutchi at a state level in India, I hope that Memons can encourage their community to actively speak and teach Kutchi. Otherwise, if the language were to become extinct, would Memons, likewise, cease to exist?

References

Abdur Razzaq Thaplawala. Memon Community and Preservation of Identity. Retrieved November 4, 2018, from http://www.as-sidq.org/

Anton, Lorena. (2009). On Memory Work in Post-communist Europe: A Case Study on Romania’s Ways of Remembering its Pronatalist Past. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures. 18. 106-122. 10.3167/ajec.2009.180207.

Bernal, V. (2017), Diaspora and the Afterlife of Violence: Eritrean National Narratives and What Goes Without Saying. American Anthropologist, 119: 23-34. doi:10.1111/aman.12821.

Heller, M., & McElhinny, B. S. (2017). Language, colonialism, capitalism. University of Toronto [Ontario] Press.

Khosravi, S. (2011). Illegal traveller: an auto-ethnography of borders. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nasreen Sattar Sait. (2014). The Memons of Kutch. Hyderabad: Safina Towers.