Undergraduate students in HUMS2101A Art from Antiquity to the Medieval World recently completed an Art in Quarantine assignment. Based on the #artinquarantine trend that emerged on social media in March 2020, the assignment asked students to choose an artwork from the textbook and to re-imagine it for the twenty-first century.

Students familiarized themselves with scholarly interpretations of their chosen artwork then re-created it using everyday items available at home. In an accompanying essay, students analyzed and interpreted the original work of art and reflected on the process of creating an updated version. Importantly, in their essays students connected issues of the past to ones they are experiencing in the present day. Students embraced the unique challenge of this assignment, which was designed to hone their visual and contextual analysis skills.

A Youth Pouring Wine into the Kylix of a Companion (c. 480 BCE) by the Greek artist Douris provided the starting point for Hope’s re-creation.

“In my re-imagined work—A Young Couple Quarantine at Home During a Pandemic—a Classical Greek ceramic vessel is reformed into a modern tondo,” Hope explains. The scene is filled with familiar objects: an overflowing laundry hamper, cloth masks, a bottle of hand sanitizer, and a vacuum cleaner. The two contemporary figures mirror the poses of the figures depicted on the original kylix. In lieu of wine, however, hand sanitizer is the focus of the interaction. And it was human interaction that Hope wanted to highlight in the midst of the pandemic: “I aimed to convey a message about the small, transactional intimacies of everyday life. In our lives today, I feel that the seemingly mundane moments are quite the opposite: that something as simple as touch has reaffirmed its powerful force.”

Emilia created a self-portrait using instant ramen noodles to mimic the hairstyle seen in Young Flavian Woman (c. 90 CE).

The assignment gave Emilia the opportunity to learn more about female hairstyles and adornment in ancient Rome. The process of creating the self-portrait was one of trial and error. “I reflected upon the notion that this is likely a similar struggle that an ornatrix (hairdresser) had to go through when creating the elaborate Flavian hairstyle,” she wrote. “My choice to use ramen to replicate the Flavian woman’s hair transformed the image from a woman of a higher class into what I consider to be a university student like me; what struggling university student does not have a few packages of instant ramen in their kitchen?”

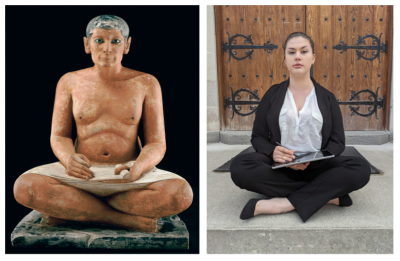

Gabrielle created The Seated Journalist based on the ancient Egyptian statue The Seated Scribe (c. 2450–2325 BCE).

“I chose to recreate The Seated Scribe because, as a member of the Journalism major at Carleton University and an avid writer myself, I felt a sense of shared history with the subject,” she wrote. Gabrielle explains how she recreated details of the original statue that she learned about through her research: “I used Gerry Dee Scott’s analysis of scribal garb, hair, and poses to help me imitate The Seated Scribe, where the subject is in ‘Scribal Pose A,’ wearing a ‘Style 4’ haircut, and a ‘Type i’ apron.” Gabrielle holds a digital pad and electronic pen—modern writing tools that have replaced the papyrus and reed brush used by ancient Egyptian scribes. “Though the role of writers has changed between The Seated Scribe—noting and recording everything—and The Seated Journalist—analysts and commentators—I connected with a shared sense of responsibility between myself and The Seated Scribe as I imitated his pose.”

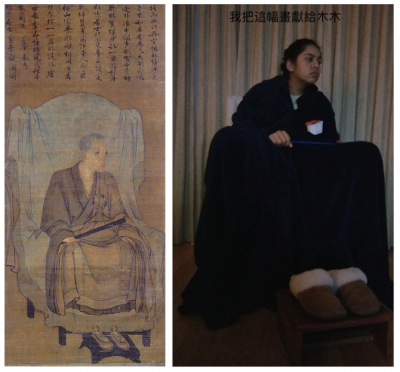

Moobinah took inspiration from a thirteenth-century chinso portrait of the Chinese Chan master Lanxi Daolong.

In her version, Lanxi has been replaced by a high school student seated in an armchair in front of a television. Her face is illuminated by the soft glow of the television set, a formal choice that Moobinah made to mimic the “hazy low illumination” present in the original portrait. Engrossed in the plot of a popular Korean television drama, the figure avoids other responsibilities. Moobinah explains, “Chinso portraits were given by Zen masters to their disciples once they completed their training. They can be considered a certificate of academic achievement, like a diploma. In my own portrait, I wanted to create a certificate of ‘academic avoidance,’ so to speak.” The message is especially relevant today. “I chose to highlight the hidden signs of mental health challenges in my recreation due to the rise in Canadians—especially students—who have reported lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Ben wanted to learn more about the Mask of Agamemnon (c. 1600–1550 BCE), a Mycenaean funerary mask that we studied in class.

He used aluminum foil to sculpt his own version of the mask, adding a medical mask like those worn during the pandemic as another layer of meaning. “To re-contextualize the Mask of Agamemnon, I took a contemporary example of a ‘death mask,’ that being a medical mask worn in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.” The relationship of the mask to Mycenaean conceptions of death was a topic that Ben explored in this assignment. “We, like the Mycenaeans, owe a great deal of our sense of identity to the masks we wear. When death is a constant in day-to-day life, we rely on the mask to ensure our identity survives, be it presently or posthumously.”

Veronica used the opportunity to learn more about votive figures (c. 2900–2600 BCE) from early Mesopotamia.

Veronica explains, “The purpose of these votive figures in the ancient Near East was to present the spirit of an individual in eternal worship to a god when the physical body could not be in the temple.” For the assignment, Veronica assumed the distinctive pose of the votive figures. “My hands are clasped in front of me like the hands of the statues, but instead of holding a ceremonial object, I am holding my phone…. Personal cellular devices often find themselves at the center of our world, especially for young people like myself, so it is one of the main components of my re-creation.” Other objects have been included to allude to the particular challenges that university students have experienced during the pandemic. An Amazon package and UberEats order are relatable details that signal how habits of consumption have shifted during the pandemic.

Ellis found inspiration in a fifteenth-century devotional fresco, Fra Angelico’s Mocking of Christ with the Virgin Mary and St. Dominic (c. 1441–45).

Through research Ellis discovered that this fresco would have served as a model of behaviour for the monks living in the monastery of San Marco, where the fresco is located. Like these fifteenth-century monks, Ellis emulated the scene, albeit using digital photography. Ellis posed as each figure in the fresco and used digital collage to create a single image. This required close inspection of the original work of art. “Since I had to look so closely at the art, I noticed a lot of small things that I might have otherwise looked over. For example, I found the thorns on Jesus’ circlet, which are small and very easy to miss.”

One of the advantages of studying art history at Carleton University is the ability to view works of art in real life through visits to our national collections. Since in-person visits to local museums and galleries were not possible this year, we embraced social media and the digital environment with this project. The assignment was based on Dr. Alena Buis’s Art in Quarantine activity, which in turn was inspired by Dr. Ellery Foutch’s class project involving tableaux vivants. Art history faculty across Canada and the United States have shared resources and strategies that respond to our present teaching conditions, and I am grateful to be part of a community of art historians who are devising innovative solutions.

Visual art is a powerful means of expression that can communicate ideas that may be difficult to articulate through language alone. Undergraduate students have certainly faced a unique set of challenges during the pandemic. This assignment gives insight into how students have responded to these circumstances with creativity and resilience.