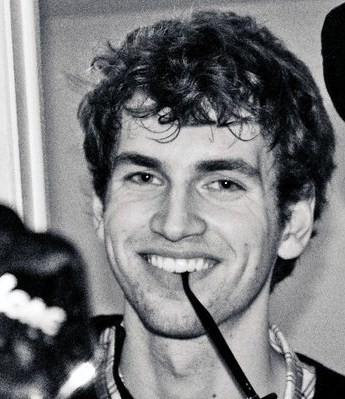

Retrace Marcus’s journey through third and fourth year English at Carleton on this candid, funny, and insightful blog. Having graduated from Carleton in 2013, Marcus is currently pursuing an M.A. in English at the University of Toronto.

Retrace Marcus’s journey through third and fourth year English at Carleton on this candid, funny, and insightful blog. Having graduated from Carleton in 2013, Marcus is currently pursuing an M.A. in English at the University of Toronto.

MEET MARCUS CREEGHAN, BY MARCUS CREEGHAN

October 14, 2011

As my first blog post I thought I’d interview myself just to give the impression that there is actually a human being on the other side of all this. Here it goes:

Q: So how long have you been at Carleton University?

A: This is my third year in the English program.

Q: What made you choose Carleton?

A: To be honest its main appeal was that it was somewhere new. I was born and raised in southern New Brunswick and knew that I wanted to go to school outside the province. One day a recruiter from Carleton came to my high school and that sealed the deal. I wish it were more interesting than that, but-

Q: So what you’re saying is that you’re capricious, kind of a goes-which-way-the-wind-blows kind of guy?

A: Well, I don’t know about that. Question seems a bit hostile…

Q: Well I’m just letting you know how you come off to other people, okay.

A: Alright, thanks I guess.

Q: Sure. How would you describe your experience in the English program?

A: It’s been really good actually. I’m always impressed by the quality of the profs at this university. I think I had the expectation when I started that there would be only a few profs that really knew how to engage with a class, but I’ve found most of them to be really great.

Q: When you really need that A+, are you willing to flirt to get it?

A: Umm, no. Actually, I think me hitting on my profs could only hurt my marks.

Q: Well the way you went on and on about how good the profs are, y’know, I figured there was something behind that.

A: Yeah the answer is no, they’re just a talented group of people.

Q: See, cause that’s exactly what you would say if you were the department tease.

A: Did you run out of questions or something, cause this is really inappropriate.

Q: Alright, alright. Is there anything you’d like to see improved within the program?

A: Well, it’s actually something I see already in motion. I’d like to see the students come together a little more often. And I think we’re seeing a real concentrated effort by the department to organize the kind of events that are going to make that happen.

Q: Alright kiddo’ you’re kinda’ boring so I’m gonna’ wrap this up, anything to say before we go?

A: Just that I hope people will enjoy the blog, and that I encourage them to send me feedback at mcreagha@connect.carleton.ca

NOW. NO, NOW…OKAY, NOW.

November 14, 2011

This is dumb, all I have to do is stand up and leave.

I stay seated.

My fellow students, at some point in your academic career chances are that you’ll have to leave a classroom mid-lecture. This is always an awful experience, bound to inflict permanent emotional scars and leave you slightly shell-shocked. An English lecture is at its best when it is an amorphous blob of ideas shaped only by the jello mold that is the prof’s knowledge. Piercing this fugue of thought without offending anyone takes skill, takes finesse, and mainly: takes patience. My enemies of the day are the clogs. A clog is a student who tends to preface any comment that they make with some particular strand of arcane knowledge that they are eager to show off, (“Well, I know from my deep reading of Nietzsche’s grocery lists that…”) and who finds the value of any comment to be directly proportional to the time it takes to deliver said opinion. A clog gets its name in part from the way they clog up an argument but also because they like to dance around their point. If I sound bitter I apologize, I have been a clog, and no doubt – when the mood strikes me – I will be a clog again. I’m only identifying the breed, not calling for their extinction. Still on this particular day the clogs were in my way.

You see, it was the first day of the English faculty’s Full-Stop Fridays and for blogging purposes I felt I should be there. Eventually, I scrounged up what little shreds of courage I own and slipped out while a clog was inhaling deeply. So Full-Stop Fridays is a kind of social event meant for English majors to gather together and collectively unwind. Usually the thought of meeting so many new people at once would give me the sweats in a way that’s really nobody’s business, but luckily Reliable Roommate had promised to come with me. Reliable Roommate is punctual and friendly and great at filling conversational pot-holes of awkward silence – basically just exactly the type of guy you’d want with you at an event like this. Arriving at Olliver’s I started walking to the back of the bar, where I stood still and realized, with not a small amount of horror, that I had no idea what the people I’m meeting looked like. Now, if it’s true what Woody Allen said that 80% of success is showing up, I’d like to add that 80% of showing up is knowing where you’re supposed to meet. And at this point I didn’t have any idea if we had a set table, or if we were supposed to meet up at another location first. On top of this, Reliable Roommate was nowhere to be found – very out of character. A moment before panic set in a troupe of profs that I recognized entered the bar surrounded by students. We grabbed a table and got to talking. Reliable Roommate showed up and took the seat next to me. We group-laughed at the tropes of English major culture, and tisk-tisked that we don’t collectively hangout more often, and during the group conversations I was introduced to the prof of the American Culture class I was dying to get into. Good news! She could let me into the class even though it was full. And as if I wasn’t already fully satisfied the waiters then brought us free food.

I’ll admit there is a motive behind this blog post. There is (gasp!) a moral to this story. Basically I know that as a group we English majors tend to be shy and averse to group activities, but these events can be a lot of fun and rewarding, if for no other reason than that they usually feed you. So even if your main motivation is just hunger, I’d encourage you to show up next time.

SECOND TERM

January 23, 2012

It’s second term again. I know this because the -20 degree weather is charitably distributing free botox to the scarf-less.

Most English majors are experiencing a relaxing calm. We’re past the weird behavior instigated by cramming for first term exams-My habits being to binge on Dr. Pepper and Chicken McNuggets (a food toward which I have a lasting fascination, seeing them as a kind of film adaptation which makes only the most cursory references to its source material. “This meal is based on a true poultry”). And, the looming threat of any really important work hovers non-threateningly in February.

The best way to take advantage of this small window of leisure might be to participate in some of the events going on within the department. This Thursday is the Poetry Recitathon for PEN (Jan, 26 Dunton Tower 2017 4-6pm).

Also good to keep in mind The Wilde-est Home Video contest that the department is putting on. Parody any work of literature studied this year in a video, post it on YouTube and send the link to the department to be eligible.

For those of you who were in Prof. Barrows 20th Century Fiction course you should know that as of the new year Joyce’s work became public domain, so no fear of any nasty litigation if you decide to finally take your frustrations out on Finnegans Wake in the only way that really matters: by defacing it on the internet.

A NOTE TO NEW UNDERGRADS

September 24, 2012

I never really get any better at the full-court press of a new fall semester. The act of actually going out to buy my textbooks always seems to throw a thoroughly cog-stopping wrench into my entire schedule. Pile on the fact that this is, in all likelihood (let’s keep our fingers tightly crossed on this one) the year I graduate, and I would say that I haven’t been this stressed since my freshman year. Now I could sidestep this anxiety entirely by gorging down a season or two of some fantastic TV (I still haven’t watched Breaking Bad ((I know, I know, please borrow some of the surrounding to bracket your contempt, I’ll get there eventually)), but like any good masochist I’ve chosen instead to channel my uneasiness. This is mainly because after four years of university I feel like I have a duty to throw some of my hard-earned knowledge back at the little whelps walking these hallowed halls for the first time.

And if there’s one thing that I wish someone had said to me, or at least acknowledged in a gruff avuncular kind of way, it’s that there is an express lane to this whole process. That just to the right, two blocks away from our gridlocked four-year academic street, where the cars sit bumper to bumper, and life can be a living hell at times, there is a smooth country road that you would only have to share with the sunshine, and by which you could get where you’re going with half the effort. On this side road you become a chameleon, your cognitive independence disappears the moment you step into a classroom and you drift through to a diploma with the least amount of push back possible. You show up to class, you get good grades, because good grades are what you get. It’s who you are. But as far as soul-searching goes (and I think that self-interrogation is still a major part of this stage in our lives, however much the idea has been satirized), this process is a dead end. And so the daunting task that I’m going to try and set for myself here is that I’d like to convince you to stay in the traffic, even while being fully conscious of this infinitely more comfortable road, so close it’s like, in your peripheral vision.

And maybe the toughest part of sticking to this rougher life is that you absolutely cannot write papers that you don’t believe in. Now, many of you probably already have friends who boast of how they can fake their way through any essay by hog-tying together wisps of theory, some political self-righteousness and a basic understanding of semiology. But what this process discounts is that you are actually just cheating yourself. One of the main skills that this major can teach you is that it is entirely possible to feel a part of the struggles of other minds, from other times. And if you are constantly holding yourself at arm’s length away from the text, you are being deprived of the chance to recognize yourself within them, which in itself make it almost impossible to put in the real blood, sweat and tears that this work deserves. And this fact orbits what is really my main point. This is essentially a DIY major, the entire infrastructure of the English department exists primarily to get you in the ring with your own personal demons. But that’s about as far as we can go. Once you’re between the ropes it is on you whether you’re willing to bring to bear the courage, self-awareness and straight up effort required to go nine rounds. Don’t argue points because you think they’ll sound smart, or because nobody will know that Barthes said it first (who reads Barthes, anyway?). Argue them because they address issues that make your guts queasy. I want you to feel your writing jitter down your spine, and send sparks zapping out your fingertips. I want your relationship with your work to be almost bodily disturbing. If the stakes aren’t that high you are depriving yourself of a chance to expand your experience of the world. My warning parable of choice for this is the work of Hemingway, who started his career with a bullshit detector so fine he could snipe red dots on the sweaty forehead of his own arrogance and anxieties, but who, by the end, acted as kind of custodian, polishing the smiling face on the statue of his persona. I know this may seem like all too many peanuts in the grand scheme of things and if I seem overly precocious or melodramatic on this issue it’s only because I know myself well enough to acknowledge how available I am for these perversions. My ego is large enough to contain the rationalizations of a pseudo-artist, and it’s a goddam daily struggle to force myself into taking the harder (if eventually more creatively fecund) path. In summation: any time you lie to yourself, you inhibit your ability to recognize a crucial, life-and-death type truth later on.

And the first thing I’d like you to admit to the mirror is that you’re not nearly as clever as you might imagine. I come from a small town in southern New Brunswick where reading is seen in the same light as, say, a prostate exam. Yeah, it’s probably a good idea to do it every couple of years or so, but if you start to enjoy it – well, then, we’ve got a problem. As a result, I am well versed in the experience of being the big fish in a little pond. But let me assure you – there is a howling, intellectually stratified, ocean out there, and it likes nothing more than to shove little-pond-big-fish down its massive gullet, as our hopeless victim screams: “But I get HBO!” while hanging precariously from the beast’s uvula. And speaking as a dutifully retired brainy-prick I know how unwilling you might be to receive this information. To tell a smart kid that they’re not smart enough is always dangerous. We neurotic schmucks have had to shore up the minor intellectual differences between our peers and us in a desperate (and altogether useless) attempt to brace ourselves against some guns of Navarone sized self-hatred.

But coming to you as someone who’s at least in the process of showing his ugly mug on the other side of this struggle, (and if I have any authority in this weird screen-to-screen conversation that I’d expect/want/ need to have with you younglings, it is as someone who has been in the same brain space as you might find yourselves inhabiting at this very moment) I promise you that once you abandon your pretensions of exceptionalism, rather than being alone, un-special and unloved, you will instead finally be able to do the kind of nose-to-the-dirt level work that is really meaningful. The kind of work that grounds you in the realities of your situation and actualizes you as a living, breathing human being in the process of growing intellectually, emotionally and interpersonally. The kind of work that makes pregnant women jealous of your glow. And, if you check in for the daily nine to five, the kind of work that ties joy and pain together so irreparably that you begin to realize not only are they deeply, almost incestuously, related, but that they are actually coterminous. And you know that wound that you hide under several layers of steel chest-plate armor, that insecurity which you go to such dickish extremes to camouflage? Well it is your struggle with exactly these indelicate situations that is the source of some of the most noble and admirable qualities of your personality. So don’t disappear. Don’t hide yourself away for fear of being judged harshly, or because there’s less friction that way. I want you to be seen, make me know you. Please.

WRITER’S FESTIVAL

October 22, 2012

Joshua Ferris’ first novel Then We Came To The End was exactly the kind of over-clever (it’s written in the first-person-plural, as in: We roll our eyes at the debut novelists anxious bid for critical attention) fiction with a heart of gold that was my bread and butter in second year. And his follow-up The Unnamed was an uncompromising nod to Samuel Beckett that showed the author was interested in more than just proving how quirky-smart he was. The healthy respect I now have for Mr. Ferris was then a weird kind of idolatry. In a publishing industry that too often values lyrical realism over any genuine attempt to make a reader feel estranged, or uncomfortable, or at least sweaty in a way that calls for a new layer of deodorant, Mr. Ferris was proof positive that it was still possible to pursue weird artistic projects without sacrificing the kind of book sales that allow you to, say, provide for anyone other than yourself and maybe a pocket-sized pet with a Vitamin D deficiency. So, when I heard that he was coming to Ottawa for the Writer’s Festival I was understandably excited. But to tell this story properly, I have to begin at the beginning.

I had been seeing a girl who worked nights at a call center. Since I had classes all day long, we missed each other coming and going. And so we started leaving sticky notes for one another as a cute way to stall for time while we thought of better ways to fix this mess. But the little, yellow pad became the launch site for a passive-aggressive Cold War. Little land mines left on any surface that would stick, these notes got more and more barbed and prickly as we both got madder at our situation. Our mutual friends, as well intentioned and inept as UN peacekeepers, would cordon off the weekend as a zone of Swiss neutrality. But you’d be surprised the level of trauma you can fit in one sunny inch squared. Especially since she quickly made herself a master of the medium, writing what has to be the Citizen Kane of subtly recriminating casual reminders. Stuck to one corner of my laptop’s jet-black screen, the missive: “If you want to connect you have to pay your part”. Although perfectly innocuous to anyone looking in from outside, it’s slightly cheesy subtext, with that lilting suggestion of “play your part”, was all too clear to me. And of course she would be beautiful as she penned her attack. I can still imagine it so clearly. With the eraser head’s pink nub resting on her lips (she had a taste for everything), looking out the window with the light at just the right angle to suggest a eureka moment. Legs crossed with the outstretched foot bobbing, and the pendulant shoe threatening, like the executioner’s axe, to fall. The whole back-and-forth was like playing chess through the mail with a convict, if this jailbird happened to be a Grand Master with a genius for psychological deconstruction.

And yet if she was wearing a jumpsuit of black-and-white stripes, I had on a much darker costume. Maybe green skin and neck bolts are most fitting, ‘cause I’d Frankenstein-ed myself into a Milton-spouting mess of muddled ideas. Fresh off the cusp of some disease, (at one point weighing in at a whopping ninety-five) I had abstracted myself straight out of the land of the living, and in many ways, although bodily recovered, my mind was still stuck in the prism of a sick man’s solipsism. And there’s nothing like weakness to make a boy want to pick a fight. Think of Captain Ahab, no doubt with his spindly peg leg on his mind, shouting: “I’d strike the sun if it insulted me!” I’d been stalking conflict in a similar way, intuiting menace in everything that breathed.

Now my roommate at the time was the spitting image of the young Robert De Niro. If all the people of the world were marked a spot in one universal crayon box, he would be the burnt umber to the Raging Bull’s Falu red, which is to say, right there, shoulder to shoulder in the wax rod role call. And he was just as aggressively charming. So seeing me in a slump he all but forced me to go to the Writer’s Festival event that he knew I’d been interested in. A thimble of whiskey, and a kick in the butt were his gifts to me, and they were enough to screw my courage to the sticking place.

Arriving at the Mayfair I was slightly shocked to find that you could count those in attendance on two hands. And we all sat so far apart that it had the distinct feeling of some X-Rated theatre. Which ended up being a stunningly appropriate comparison because the questions at these types of thing tend to be a squirmy kind of intellectual masturbation. “Mr. Ferret, I liked your book but it seems you forgot to include my pet project in the plot, would you agree that this was a gross mistake?” This couldn’t bother me though; readers have always been a cast of clowns that I can’t help but love. What really got me in jitters was the entrance of Ferris himself. He sat an aisle over and the quick contraction of book flap photo to flesh and blood figure made me almost queasy with nervousness. I had one of those moments where you see yourself from a third-person perspective and become acutely aware, on an almost Buddhist-like level, of your own body. Sweaty and shaking, why didn’t I shave before leaving the house – will I look like a crazy person with slight scruff on my chin – how’s my breath – can I talk to him? Suddenly it felt as if someone had laid anchor on my lap and exchanged my feet for cement blocks. I came to talk to him, I have to talk to him. The better angels of my nature jackhammered my cobblestone shoes and I waddled Charlie Chaplin-style over to flagellate myself in front of the rex at rest.

“Hey, uhm, I’m a big fan” (Really?!)

A smile. His hand is offered as he stands. I am six foot three and looking up. This man is a giant.

“That’s so nice of you to say, thanks for coming out.”

“Do you, well, would it be possible. If you have time, could I maybe talk to you after?”

“Oh sure, who are you with?”

…

…

“The Charlatan, for the university down the road” (This is a lie, and all the worse because he was about to find out just what caliber of journalist I was)

“Oh okay, cool. Sure, I should have time for that.”

Don’t ask me about the actual event. I spent the whole time scribbling questions down in a tiny notepad (that’ll look professional right?) in anticipation of the now much-more-formal-than-intended conversation to come. A disclaimer: like most people, I consider myself at my intellectual prime at 3am while drunk out of my mind in the corner of some alleyway pizza place, growing pustule-like out of the side of some bigger host building. Y’know the type that wears the greasy smudge of smog from its ovens on the wallpaper with pride. Only there and then, in my personal urban Eden, does the crippling self-awareness disappear. And this was no pizza parlor. So as Ferris’ felt folding seat squeaked into a right angle beside me, I swear my insides liquefied and came gushing out my mouth.

I tried to ask him questions, but I ended up just name-dropping trendy authors with the kind of insecurity that others might wear while flashing the relevant documents for a gallon-hat wearing border guard. I’m one of you, I swear. Part of the problem was that I came in search of a conversation and somehow slipped my way into an interview, which I was frantically underprepared for. But another issue, and this’ll sound strange, was how nice he was. His curious smile (no doubt as surprised by my presence there as I was) just felt more welcoming than the situation warranted. If he had been a stoic Kilimanjaro, over whom you could only gain purchase with the icy violence of a pickaxe, I might have settled into the role of some wounded fanboy. But he seemed genuinely happy to sit and speak with me, which made me even more grateful, which made me even more nervous about living up to his kindness.

About four or five questions in he gave me a sidelong glance and said: “Shouldn’t you be writing this down?” Of course. Real interviewers take note of the answers they receive. But they never taught me that at imaginary journalist school, yet another example of the failure of our educational system. Mr. Ferris might now have realized how open he was to misquotation, and might have been imagining, with no small amount of dread, the fraudulent headlines of the university dailies to come: Joshua Ferris Not All That Opposed To Certain Kinds Of Bestiality, but if he was, it didn’t show, and he guided me through his own mock-trial and out the door where he wished me well and to: “Be safe.”

I jogged, stumble-sprinted my way home. The poor boy thinks he can outrun shame. And threw my body down on residence bed. Faux-De Niro had flown the coop, no doubt off to encourage other Evel Knievels into jumping that extra bus that’d leave them (like me) in a pulpy heap, with axle rod wed round the spine like blushing bride’s blood diamond ring. But seeing my signed books, I just could not stay mad at him. If this debacle had in some way shown me the distance between myself and my ideal, it had at least become clear that these two worlds do intersect. And the fuzzy violence of my crossing over, for a moment to haunt that other world, made me aware of something that I had been neglecting for an unseemly long amount of time. Mr. Ferris’ willingness to acknowledge me as someone who deserved his attention forced me to come to terms with how circumscribed my own consciousness had become. I suppose it is a symptom of my penchant for getting lost inside my own head that I can easily convince myself that I don’t orbit other people. And even if I don’t intend to isolate myself from the rest of the world, it doesn’t change the fact that out of a much-derided but still all-powerful kind of insecurity, which operates like a hunchbacked, shady power player, running the government from a smoky backroom, I undercut other peoples’ efforts to connect with me. Every (wo)man is an island, but the brave ones build bridges.

I called her later on that night. I need to see you. Face to face.

Fall 2012 (Oct 26 to Oct 30) edition of the Ottawa International Writers Festival

ONE MAN’S TRASH

November 26, 2012

The dumpster, all tumored with lazily tossed garbage bags, jittered from side to side, as if prepping to explode. A few feet from its open hatch, I stood holding a little nine-inch TV set, with power cord looped round its slightly askew bunny ears.

“Come on, Dave, this is disgusting. Just get an extension from the prof.” I said.

As Dave rustled around in the big, rusty box his feet went “sphlock-sphlock”. A noise that implied he was rooting around in the kind of bubbling trash that decomposed begrudgingly, and only after the collective chemical process had become so acidic as to turn this soupy mess into a bio-terrorist’s backyard workshop. His head popped out and he gave me an ‘oh-please’ look, ‘cause clearly I was the lunatic in this situation.

“You know I can’t do that Marcus.”

Dave took a scorched-earth policy to end of term assignments. As soon as he hit word count he printed the sucker out and deleted the document. It worked as a kind of digital baptism, purging him of the shame he felt when, in the heat of the infamous pre-exam crunch, he inevitably dished out one or two papers that were of less than stellar material. To those of you with superstitious inclinations you will no doubt be wringing your hands already at the spitting-in-the-face-of-fate nature of Dave’s habit. But you need not question your long-held beliefs because karma is just as fickle as you remember. And Dave had accidentally tossed the academic baby (and what a little homunculus gremlin it was. When Dave knew he didn’t have time to give a paper its proper due, he made phoning it in seem almost heroic, stressing his own incompetence with glee. I’m exaggerating, but not by much, when I say that he would turn in easy-answer papers with titles like: Was Nazi Germany Anti-Semitic?) out with the bath water.

“Well I can’t stand guard any longer, I have to get this to Grant before my meeting with Professor M.”

The TV I was holding was, thankfully, not the fruit of Dave’s foraging, but instead a clunky, dusty, melancholy little thing that had sat expectantly in the corner of my rez room, begging me to use it (just once!) before its circuits finally fried. I had promised it to a pal o’ mine named Grant from my Japanese Language class, the game plan at this point being to teach English in Japan after my undergraduate degree.

“Mom: I wish you’d reconsider, that whole island’s gone radioactive.

Me: Well, maybe I’ll get superpowers.

Mom: Or you’ll turn into Godzilla.”

Grant was the kind of kid that was raised on anime and manga comics. Steeped in the finer details of reading backwards and other niceties of Japanese culture he had shot to the top of the class. Grant has a kind of mellifluous fluidity in foreign tongues between which he can alternate with the speed of C-3PO. And just like that bronzed protocol droid he was annoying if for no better reason than that he insisted on playing by the rules that the rest of us ignore on a daily basis. An indicative piece of Grantology is that, directly opposite to the ingrained nature of every single human being on the planet, he always learned the curse words of a language last.

We met somewhere deep in the tunnels as if surreptitiously exchanging coded-information.

“O genki desuka Maruku-san?”

“Grant, you’re from Brampton.”

“It’s important to practice. Maybe you’d be doing a little better if – ”

“Yeah, well, here’s the TV.”

I really did like Grant, but in case it wasn’t clear, a crippling jealousy prevented us from having anything more than the most cursory favor-for-favor kind of friendship. It was around this time that I realized that learning Japanese would take many more years (!) than I was willing to give it. And Grant’s facility with languages of all kinds (he also knew French, Spanish, German and probably Ancient Sumerian and Martian too) contrasted unflatteringly with my more monolingual bend.

Oh, English: light of my life; you slutty, Lolita language, so eager to soak in other lexicons. You’ve got no boundaries: a universal space without the void – a pier to no bad cove. They tried to keep us apart with ten years of French immersion and that francophony marriage only made me love my mistress more. As a result every foreign tongue is judged harshly against the silhouette of my Anglo-Saxon angel, making it near impossible for me to flirt with the harsh plosives or slippery loose syllables of some more distinguished, dame diction. Still it’s not all sob stories, because in exchange for this damnable tryst I’ve been given the chance to hit certain heights of cunnilinguistic bliss. But maybe I’m not being humble humble enough…

Unburdened of my televisual ball n’ chain, up in Dunton Tower, I met with Professor M to discuss a short story I’d written that he was graciously reading over. I feel I must have been fishing for compliments after my demoralizing encounter with MacArthur Genius Grant. Luckily, despite the Bond-villain pseudonym I’ve given him, Professor M is an incredibly generous human being and he gave me the kind of ego-soothing encouragement that the doctor (had he been called) would have ordered.

On my way out I ran into Dave, coming from another prof’s office.

“I guess this means you found it?”

“Yeah, but apparently my professor isn’t in the habit of accepting work with mustard stains and, like, little fly corpses strewn all over it.”

“Damn ivory tower academics.”

“I know, right? Anyway, she says I can bring in a clean copy tomorrow, so, no gristle off my bone.”

“What?”

“It’s a saying.”

“No one has ever said that before.”

“Well, can we say it’s a saying?”

“Yeah, sure, I can’t see why not.”

The elevator pinged and we plunged back into the filth.

UNCLE GEORGE

January 14, 2013

The holidays have just rolled past and for most of us that means the carnival of all our extended family have made the rounds as well. And although I don’t want to get into too much personal detail here, I’m positive that every English major has had a similar conversation (at least once) with a member of his or her kin and clan as the one I’m about to describe, so I feel like this might be pertinent.

For me it always comes from my Great Uncle George, who operates in a series of superimposed cycles stretching outwards, so that looking at one’s watch at any point in the day, or checking the calendar on any day of the year, you could guess (by time alone) what exactly Georgie might be doing. His endless repetitions are probably the whispers of some incoming senility, but they are also the product of his divorce, at 58, which pretty much sent him reeling, emotionally speaking, into the safe-track trenches of a world without painful reminders. His advice, and he is a big giver of advice is just as repetitious, every time I see him he always hits me with his cautionary tale: “And Marky-boy, Malarky-boy, remember this, if nothing else: The only thing stupider than getting married is getting divorced. That’s how they getcha’.” Who and why: forever obscure.

Uncle George has spent his life in one long, sustained verbal performance. And he’s picked up conversational tricks from all sorts: the old Jewish men eternally martyred in his retirement home; the Irish boyos, verbally clubbing one another for sport, with whom he’d worked the mills; and not nearly least of all the Newfies he’d met out on an oil rigger. This synthesis of speech patterns not only gave him interesting mixes, but endowed him with the frame of mind necessary to create whole new expressions, personally trademarked Uncle George® (my favorites included, when you asked him if he’d mind doing something for you, the response: “I’d rather be rum running across Hell’s own border”, and when you ask him where he’s been, the answer: “Oh y’know. North of the sea, south of the sun”).

As for the conversation I’ve hinted at up to now, I figure it might be best to just script out a single instance of the more general trend. And so here it goes:

Uncle George: “Now tell me this, and tell me straight, can you name me one great writer who died happy? No. They all crumple up in some garret somewhere, syphilitic and strapped with gout, alone and still growling at the universe. Science. Now that’s a profession! There you have your success on a piece of paper. A decoded the human genome, B cured polio – and on, and on, and if you’re lucky – a Nobel Prize!” Here his eyes got that fresh-minted coin sheen.

Marcus: “There’s a Nobel Prize for literature too, y’know.”

“Bah.” He waved this category away as if it were just an oversight, which had not, but soon would be, correctively deleted. “What’s important here is happiness. A scientist works towards a goal, he can measure all his success and failure against that finish line – and so he keeps his head on square. What’s a writer to do? Work to a word count? But we both know it works in no such way. And when you start to write about your friends (which let me tell you: you inevitably will), they leave out of anger. And guess what, you’re glad to see them go, because they never lived up to your wonderful characters anyhow. And there you are: alone and unhappy. Is this what you want?”

“Nikola Tesla was one of the greatest scientific minds, maybe ever, and he died by himself in a hotel room, talking to pigeons.”

“Well, at least he had friends! What self-respecting pigeon would talk to a dying poet?”

“Will you leave him alone George, it’s his passion.” Why is it that nothing marginalizes the things you care about quite like hearing your mom defend your right to be interested in them?

“What? You’d rather I didn’t care at all about his future? You’d rather I send him a birthday card n’ 20 dollars every year, like some people [I’m not exactly sure who he meant here. It no doubt involved some well-savored family wound that he’d been picking at for years, maybe decades], and we leave it at that? No such luck. I care! So sue me.” This challenge carried with it the implicit threat that Uncle George would mop the floor with you in any courtroom from here to Alaska.

“I’m not even sure if I want to be a writer, I could be a teacher – a professor maybe.”

“Ooo la-la. Professor Marcus. What, you gonna’ need to get yourself a pair of snobby glasses.”

“Uncle George, you wear glasses.”

“Aha! And who’s a bigger prick than me?’’

It’s usually around this point that he’d laugh himself hoarse at his own joke and send me off with a choice liquor order to drown out the itching in his throat. When I was small he’d always give me the slum dog milliliters at the bottom of his glass (to grow hair on my chest). It’d be easy to assume that Uncle George’s recurring lecture series on the folly of my academic path were some kind of working class response to what he perceived to be stuffy high culture. But despite his best efforts to hide it, Uncle George just overflows with good feeling for other people. And deep down inside I know a storyteller like him can’t help but perceive himself as an unrecognized poet. More likely than not his whole spiel relates back to that little dose of alcohol at the bottom of his glass that he’d force on the boy hanging round him at bended knee. It’s all a series of tests, and Uncle George wants to give the vitriol, wants to set the bar higher than anyone who might not know what he knows: that his great-nephew is just that. And that should I make that final leap, that sends me up and over, as he watches smiling from the sidelines, he can say:

“Well I’ll be damned, the sunnabitch did it.”

re: lit, life I

March 4, 2013

When I was young – say, around eight or nine – I had terrible insomnia. I wasn’t the kind of elastic kid that stretches and snaps out of their parents’ grip, rubber balling down the hall trailing a marker along the now graffitied wall. But I did drive my mom and dad mad by being just interminably awake. At three or five in the morning my parents would pound and curse at their pillows knowing that my two marble eyes were wide open, scrolling the pages of some smuggled picture book. And as it goes in parenthood, while I stayed up there’d be no rest for them either. Eventually my mom found that if she played cassette tapes for me I would at least assume all the usual positions of sleep (lids shut, two hands under the head and a gentle curling up of the legs). So I got my own boom box, hand-me-downed from a relative who once hit the streets equipped with mixtapes (which he kept in a tie-dyed fanny pack) and the conviction to bring the noise to the people.

Clearly this was a tool of immense magical power, decked out as it was with all the levers and knobs that an autocratic audiophile would demand out of his weapon of choice. And it did take me to other worlds – weird ones at that. I assume my parents trolled some bargain bin for my soporifics because they ran the gamut from the story of some Polish immigrants’ adventures in turn of the century New York – set to the tune of Swan Lake, of course; to a time-travelling tour of the Paleolithic, narrated by none other than David Suzuki.

My most memorable adventure, though, came when my folks asked an unwitting neighbor to babysit me for the night while they rushed my older brother to the hospital (I can’t remember what for, let’s make it interesting: hyper-atrophied cerebral contusion). My hapless guardian’s only instructions: for the love of God bring a tape! And this wise man carried to the manger a bootlegged recording of Lenny Bruce’s legendary Carnegie Hall performance. That’s right, the dark comedian whose critical re-evaluation of the stand-up form had viciously spliced together politics, religion, sex and all things underground came knocking on the bedpost of a pre-pre-pubescent babe in the woods. And I was changed forever. First: The Voice. Like the devil’s advocate trying to sell Moses car insurance. Equal parts shoe polish and slightly sugarcoated obscenities. I maintain to this day that my need to make words dance to the music in my head is a direct product of my having heard, in my formative years, Bruce’s inbred Yid-rhythms and the jazzy intonations of his slang arsenal.

But maybe more importantly that tape inscribed in me a deep affinity for forms of expression which function as illicit act. A hunger for art as border-hopper, as flight of refugee thoughts from one beleaguered subjectivity-state to another, and not necessarily through traditional channels of dissemination. I have always been fascinated by the mythology of the found text. Namely: how we come into contact, almost haphazardly sometimes, with the artistic work that moves us most deeply. The writers that I respond to in the profoundest way are those that deal in emotional data as if it were a prison-yard shiv: carried secretly under baggy clothing until that fatal moment of impact. “Ooo you got me!” Those writers that disturb me in meaningful ways do so by sustaining a sweaty tone of impending revelation, distending previously unrecognized feelings of loss until they reach a clicking-point, in which our deep-gut, often-glanced-over pain is reinvented as a better understanding of one’s place in a larger schema. This process, in which the damage dealt to us becomes our greatest link back into the world, gestures towards some unseen method of being healed, if only because it proves that in some ways we can communicate those private insecurities which strive always towards silence.

Sidebar: One of the hardest parts about selling people on traditionally “difficult” art is that it’s not easy to talk about why it’s great in non-sadomasochistic terms. I swear you don’t need a whip-fetish or a sweet tooth for cherry red ball gags to enjoy Gravity’s Rainbow, but then again, it couldn’t hurt. In any case the art that cooks with me (thanks again to Lenny Bruce) helps to qualify our feelings of absence from this world as a friction between the self and everything else, because it goes without saying that life is always being lived elsewhere, elsewise and with else one. What changes is our ability to reconcile that gap. It is a particularly violent understanding of human creativity, and one that relies on a kind of barnstorming bravura from its artist figures. Bruce Springsteen once described first hearing Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone” as the sound of someone kicking open the back door to your mind, and this is a close approximation of what I once thought artists were for — to shock us into our senses, to force a summit between our illusory conception of the world and some more essential, “real” experience. And my willingness to fall back on this argument got me into some deep shit, developmentally speaking. How, exactly, you might ask. Well…

By my senior year in high school, I was engaged in a Felix Baumgartnian style descent. Except that instead of free falling out of a Red Bull brand flight capsule, it’d be more accurate to say that I was plummeting back into space. Unrigged from gravity’s tender mercy and left to unspool myself out into the chilly draw of the dark universe’s dormant imagination. I’d gotten sick, like really sick, like: every morning; how could you; why me-type sick. I had an ongoing debate with the toilet bowl as to how long I could keep my food down. He usually won by betting low but I was always man enough to hug his pale porcelain sides as I drooped. To save myself from your pity I’ll just call this illness the unnamed. And under its influence I broke up with my girlfriend, quit my job, became the barest whisper of my former self and spiraled into a monstrous depression.

The overly-clichéd, but nonetheless ever-present and valid intra-psychic storms, less politely known as mental clusterchucks (which becomes even less polite if you spell it correctly) that attend any kid coming up in a world where your expectations skew jarringly away from the reality of the situation (qua the adult existence which you are ineluctably careening towards is not the stable well-oiled machine that it had always appeared to be, but instead just a vapid, less-passionate double of your already disconnected and transient lifestyle – essentially you + rent), is reason enough to lose your mind if the numbers don’t crunch quite right. And in any normal situation the ingestion of certain shady (why skirt the issue, exact status: illegal) substances would be the norm for curating these monstrous depress-ogres into some more tame natural exhibit.

But of course the unnamed requires significantly larger doses of neuro-dimming materials. Specifically an injudiciously prescribed major tranquilizer, which, relatively speaking, is the inter-continental ballistic missile to the child’s cap-gun of over the counter Advil. The overall effect of this pill being that instead of acting like a janitor, shutting off the lights of my brain room-by-room before going home to a warm meal and a lumpy bed, this megaton hammer (the pill) shut down the whole cerebral construct like that last scene in Fight Club, where a city block of commercial towers just instantly collapses, raining shards of glass onto the streets below.

It is probably one of those incredibly rare universal truths that any drug use is an act of role-playing, even down to the most domestic brands.” I’m a fully certified court-stenographer when I’m properly caffeinated, adding footnotes, with off-branching addendum to the bottoms of my notebook pages. And the crowd that’s asked to carry the weight when I crowd surf at concerts might be gratified to know that Marcus Creaghan, esquire, would never dream of imposing his body weight on other people without alcohol’s helping hand. But the danger comes from not knowing what role you are playing and why you feel this deep-set need to inhabit a character and a costume that you would otherwise never feel comfortable wearing. And to explain my situation to you I need first to say that you’ve been lied to. Because the traditional narrative of depression defines it as a kind of stasis, a scrunching up, a sitting still as the scary world storms by. But really the experience is more like an endless dynamic friction inside of you, like the deep note in Hans Zimmer’s Inception soundtrack, that wants out but which finds no avenue of escape. It is a roughshod plane of limits, and the worst part of it is the humiliating feeling that you have well and truly lost control.

In a sense it all comes down to movement. Depression creates a stark division between inner and outer worlds. And once the spaces of the outer world lose their context; once the constellatory logic, mapped out by the out flung positions of each individually lost star, drop out of the sky, leaving you with a black, suffocating drape, you’re left with no choice but to turn inwards. Which in itself forces you to redefine motion as a journey through self instead of space. But this interior motion, this tidal influx, can only be a dance of swords, in which you tear apart your insides looking for fertile earth to till. What this pill allowed for then, was a kind of circumscribing of the borders of my existence. It let me draw a circle in the sand where I could call myself king — a place from which to take the power back. If the rest of the world was drifting away like dirt thrown into running river water, then at least I could control the motions of my dulled mind. But of course this left me in a quiet room, alone, with the unnamed.

And if my inclination when it came to art was to be critically distant, to connect only when the artist was able to bridge that gap with their own mad, bad and dangerous creativity, my habits as a sick man were even more defensive. Every morning I’d slip, almost out of panic, into some gross caricature of a former, stronger self. I became a person untouchable by kindness, or humor, or sympathy. And this is how I was when I started at Carleton. Completely isolated and scared out of my mind, but also incapable of really understanding how much I was imposing this upon myself.

One of my favorite things about 80s action movies (abrupt left turn, I know, but stick with me for a second) is that they portray cab drivers as, essentially, just wayward mercenaries. Throw them a wad of bills and they become an impressive jack-of-all-trades, playing the part of your arms dealer/getaway driver/all around good-time buddy. They apparently carry an indispensable and endless cache of skills just waiting for a dead president’s apathetic grin to awaken them. In fact, I have the sneaking suspicion that the team of marines that killed Bin Laden was actually just a group of highly paid cabbies, eagerly watching the meter as they flew over Pakistan. Swooping down with air fresheners and foam dice around their necks instead of dog tags. What I like about this film trope is that it assumes that at a moment’s notice we can reinvent ourselves. That if the camera pans over our idle frame, we have the chance to rise to the occasion.

In many ways our lives are lived as narratives that breathe in the telling. But, sometimes, there lies a small slit of opportunity to change ourselves before the account is codified into myth. There may not be any real way to exorcise love’s lost demon, or to repair the damage done by the blunt unfeeling motion of life’s moving plot. And looking back only helps us to define the moments in which we still had the chance to be otherwise. But there’s a kind of blitzed out and dazzling happiness that comes from knowing you’ve cheated history. That the pieces were all in place to have you play the part of the villain’s sniveling and chronically underappreciated sidekick, but that you slipped backstage to pull an eleventh hour costume change. Because there’s one thing that all the chaos of creation can’t account for, which is that you’re the author of this story.