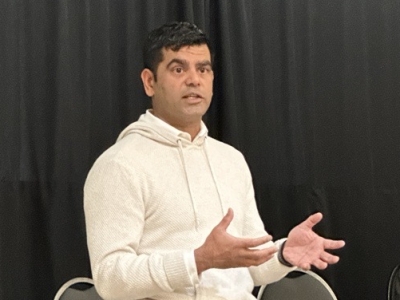

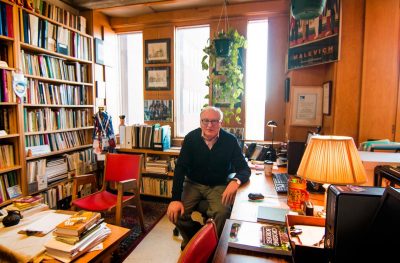

Piotr Dutkiewicz is a Professor of Political Science and European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies. Winner of the 2014 FPA Research Excellence Award.

Piotr Dutkiewicz is the editor of The Evolution of Russian Society Since 1991: Actors, Attitudes and Practices, which will be published first in Russian by Moscow State University in December and in English by Routledge in January 2016.

Growing up in communist Warsaw in the 1960’s, Piotr Dutkiewicz’s family was part of what he calls the “silenced majority”. Today, as a researcher who specializes in Russian society, he argues that current governments continue to ignore the voices of the majority at their peril.

What drew you to study the experiences of the Russian people?

I come from a country where the majority of people weren’t involved in key political and economic decisions. So the issue of being consulted, of being incorporated in the decision-making process is not only an academic question, but a very personal question for me.

You lived in Poland and then Russia during the fall of the Soviet Union.

What were the expectations of the majority of people when communism fell?

I was living in two worlds. As a Pole, I felt the high hopes, the joy and infatuation of the majority of Polish people who celebrated an end to the ideology and the subordination of the Soviet Union and a closer relationship with Old Europe.

But in Russia, I was surrounded by people who were traumatized. This huge country was suddenly divided, had lost its super-power status, and inflation was rising rapidly. They worried what the next day would bring.

But there was hope that the people would finally gain a voice in the workings of their country.

More than twenty years later, is the voice of everyday Russians being heard?

The “people” are absent from the Russian narrative and discourse. The assumption is that no one is interested in what the average Russian thinks: neither the Russian elite nor the counter-elite (the opposition). They are simply interested in access to power.

So I asked well-known Russian academics, including sociologists, economists, political scientists, and experts in regional studies to contribute to a book about the evolution of Russian society since 1991, to be published later this year.

It will answer a few key questions about how the unprivileged mass of the society—the so-called “silent majority” that makes up 50% of Russians—see themselves, how they act, what they collectively think about politics and economics, and what strategies they are taking to improve their living conditions.

What did this uncover about peoples’ lives?

This is the story of the millions of Russians who, despite all odds and turbulence, maintain the dignity of the country. They are not merely the objects of high-level decision-making, but a dynamic, adaptive citizenry. Attitudes and values are changing quickly and adapting to the changing economic environment. In fact, they restrict what those in power can and cannot do in Russia.

At the same time, we found the disappointment of the people has been a constant over the past 20 years, particularly in response to corruption and social disparity.

I met a man on the train from Moscow to St. Petersburg who works in the Kirov machine-building factory. He told me there are two kinds of Russians: those who fly overhead in their private planes and those who walk on the ground below. That sentiment was confirmed by our studies.

Your book will first be published in Russian. How do you think it will be received by the Russian elite?

Our hope is that those in power will recognize that “the people” should be at the centre of their policies. The living situation has slowly improved—poverty has steadily diminished since 2001—but about 50 percent of Russian society is living on the edge of meeting basic needs.

We see this as an early warning signal to those in power. The biggest danger for the current elite isn’t the opposition, but the silent majority.

Historically, people who are suffering, who don’t get proper care, are inclined to protest.

This can take different forms: even if you don’t have an active revolt, people can boycott the election, depriving those in power of legitimacy.

What can we in the West learn from the Russian experience?

The same economic disparity exists here and is growing, so there is the same danger here.

Russia exists in a grey zone between authoritarianism and democracy, economic freedom and political control, liberal democracy and dictatorship.

We in western countries are moving into that grey zone as we introduce limitations on freedoms based on a fear of the “other” and, more and more, limitations on means at the disposal of the majority. Our democracy is being eroded.

What do you hope for the future of Russian society?

To achieve success, leaders of the nation have to have confidence in the peoples’ judgment as to what is better for them in different situations. That’s the only possible democratic stance that can be adopted in practical political life. I hope that a new alignment of political and social forces based on that principle will eventually take place.

Friday, September 9, 2016 in Department of Political Science, FPA Voices, Institute of European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, International, People

Share: Twitter, Facebook