Carter Vance, Justin Langille and Grace Martin won the CU75 POPS graduate competition.

By Tyrone Burke

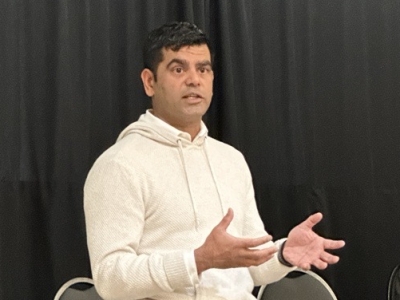

Photos by Sherry Crummy and Chris Roussakis

When it rains, it pours.

And that, in a nutshell, is the problem.

When stormy weather rolls into Ottawa, the city’s wastewater infrastructure is swamped by the deluge. Impermeable surfaces like pavement prevent soil from absorbing water. With increased water volume, the flow picks up pesticides, animal waste and other pollutants as it rushes through the city’s 2,600 kilometres of storm sewers, pouring pollutants into Ottawa’s two glorious rivers: the Rideau and the Ottawa.

City beaches close due to high counts of E. coli. Waterfront properties erode. Aquatic wildlife is killed off by contaminants and the runoff’s warmer temperature.

On World Water Day, March 22, Carleton’s Faculty of Public Affairs challenged students to find creative solutions to the problem with CU75POPS: Water.

POPS stands for Policy Options and Problem Solving, and seven teams of students – three graduate, four undergraduate – made concrete proposals on saving Ottawa’s rivers from its population. Proposals needed to consider the tools that municipalities have to influence behaviour, recognizing that most land is developed and in private ownership, and that the actions of individuals are contributing to the problem.

Andrew Eschevarria, Kyla Fisher, and Andre Karkeck won the undergraduate competition.

Judges from Carleton, City of Ottawa and Environment and Climate Change Canada evaluated each proposal for its innovation, feasibility, contribution to the community and presentation. The stakes were high, with $11,500 in prize money split between the graduate students and $12,000 between the undergrads.

Upgrading infrastructure seems an obvious place to start, but in Storm Water Shift — the winning proposal in the graduate student competition — Grace Martin, Carter Vance and Justin Langille argue that this would have limited effect, and could even make matters worse.

“The city has already made significant investment to reduce combined sewer overflows through the Ottawa River Action Plan,” asserted Martin, a student in the Master’s of Public Policy and Administration program. “Real time control has reduced overflows by 80 per cent, and the construction of additional storage capacity should bring further reductions, but our team believes that further investment in the system beyond existing plans would create a situation of diminishing returns. Such investments are invisible to the public, and do not incentivize behavioural changes. On the contrary, they can even incentivize negative behaviour as citizens believe that upgrades can continue to occur.”

Martin, Vance and Langille argue that the way forward is to reduce the amount of water flowing into the system in the first place.

How?

There is no simple answer, and that’s where the interdisciplinary nature of the competition comes into play. Teams in CU75 POPS could have no more than two team members from any one faculty, and it showed in the diversity of ideas the teams presented.

Martin studies public policy, Vance political economy, and Langille environmental anthropology. Storm Water Shift synthesizes their disciplinary backgrounds.

It proposes to incentivize low-impact development among private citizens and businesses through a pilot project to be implemented in 2019. This green approach to storm water infrastructure mimics natural hydrology by intercepting, filtering and evaporating storm water before it enters sewer systems, rivers and streams.

This can include the construction of green roofs, green walls, permeable pavements, rain guards, underground cisterns and constructed wetlands, and harnessing the existing functions of natural wetlands, forests and parks that already provide a filtration function.

Storm Water Shift proposes to do this with a two-pronged approach: outreach and economic incentives.

Success in the National Capital Region would require co-operation with the National Capital Commission and non-governmental organizations already working to safeguard the river, such as Ottawa Riverkeeper, and an education program to raise awareness of the problem, delivered through Ottawa schools.

“We need to have a collective approach to it,” said Langille, who is studying for his Master’s in Anthropology. “To work with communities that are ready and waiting for solutions they can benefit from, as well as the larger system.”

Actualizing education is another matter, and money talks.

Storm Water Shift would offer financial incentives for low-impact development measures in new construction projects and renovations to existing ones, to be applied via property taxes and water fees. Existing grant programs at the federal and provincial levels should be leveraged as well, when applicable.

“We looked at how you can use the levers of municipal policy to incentivize private actors to act in a responsible way,’’ said Vance, who is doing a Master’s in Political Economy. “How do you get them to adopt these low-impact development measures? We decided to look at taxes, to look at utility bills. What are the incentives that people respond to? Usually it’s in their pocket book somewhere.”

The team‘s own pocketbook will be padded with the competition’s $7,500 first prize, with runners-up Shirley Ngai, Joshua Russell, Pengcheng Ge and Robbie Venis taking home $2,500. Third-place finishers Tanya Locke, Jing Zheng, Narek Martirosyan and Emmanuel Olaide pocket $1,500.

Undergraduate winners were Kyla Fisher, who is studying Economics; Andre Karkeck, who is studying Political Science; and Andrew Exchevarria, who is studying Computer Science.

Second prize went to Nour el-Nader, Priscilla Pangan, Faizah Ahmed and Tanya Kunwaar. Third place went to Catherine Kelly, Faraz Maqbool, Saambavi Paskaran, Marie Gelineau and Sarah Shires, and fourth to Mary-Jo Hass, Jingni Wang and Gregory Guevara.

“All of the presenters really put a lot of thought into it,” said City of Ottawa senior project manager, Darlene Conway, one of three judges in the grad student competition.

“They came up with some really worthwhile results. They had a very specific task of how to reduce storm water runoff that’s polluting our creeks and rivers, and they came up with some really concrete approaches. I should actually get their presentations and take them back.”

Monday, March 27, 2017 in FPA Research Series, Institute of Political Economy, News, Policy, Public Policy and Administration

Share: Twitter, Facebook