By Karen Kelly

Growing up in a Anishinaabe Wiisaakode (Ojibwe Metis) community in the 1960’s, Social Work Professor Patricia McGuire and her siblings knew exactly who the government-appointed social worker was and what happened when he came to their village.

“We would go to a lookout high above the community where we could see and hear everything,” recalls McGuire, who grew up near MacDiarmid, Ontario, close to the Biinjitiwaabik Anishinaabe reserve near Thunder Bay. “When the white man with the white car came, children would start disappearing.” That included her best friend. She and her friends guess more than 60 percent of the children disappeared over two years.

The social worker was just one of many trusted officials—including RCMP officers, Catholic priests and Indian agents—who removed Indigenous children from their homes and communities for decades. Most of those children were sent to residential schools and never saw their families again. Thousands died, as witnessed by the unmarked graves that have recently been discovered near residential schools in Canada.

Today, McGuire is herself a social worker and part of a group at Carleton’s School of Social Work that is acknowledging the field’s difficult history with residential schools, child welfare and education. This group of social workers is committed to decolonizing and reconciling social work’s relationship(s) with Indigenous peoples in Canada—beginning with its own program.

The Emotional Burden of History

As part of this effort, McGuire is drawing on her personal experience and that of her community. She remembers her parents taking her and her siblings to live in the bush when they knew the government representatives were coming. Both of her parents survived residential school and understood the fate of children who disappeared.

“All nine children in my mother’s family were sent to St. Joseph’s Boarding School in Thunder Bay, even the four-year-old,” recalls McGuire. “When my grandfather heard they were removing kids, he decided to take the children himself and form a relationship with the school. He agreed to give the school money and provide food from the land to ensure his children were taken care of. He brought fish, birds, moose meat and berries. But the children never saw that food and were not allowed to see their parents, either.”

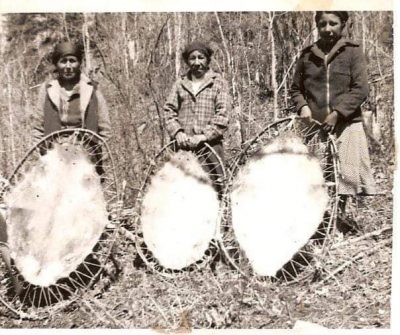

McGuire’s father, relatives, and friends

On her father’s side, seven of the 11 children in the family were sent to St. Joseph’s, as well. Her father was frequently beaten for talking back to the nuns and priests. In later years, he would look for school friends who lived on the streets of Canadian cities.

“My maternal aunt, Agnes abun Hardy, said that when the McGuires came to MacDiarmid, they would speak up and not shut up,” remembers McGuire. “There are a great number of issues to speak out against in Canada.”

McGuire has inherited the calling to be a witness to injustice. She testified about her family’s experience before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and she has been instrumental in helping the School of Social Work implement the TRC Calls to Action. As an Indigenous woman, McGuire brings a unique and deeply personal perspective to social work reform.

McGuire’s maternal grandmothers, Queen Ann, Jawmo abun, and Mrs. Fitzback.

“There was an infrastructure in place that impacted my family and all of the Anishinaabe in our area and social work was woven throughout that,” she says.

In recent years, the School of Social Work has recruited more Indigenous faculty and students and changed the curriculum to include a course in social work and Indigenous people as well as integrating content in other courses. They also plan to integrate critical histories of colonialism into current courses.

“During the long period of residential schools, the profession of Social Work stayed largely silent. During the Sixties Scoop, Social Work was actively involved in apprehending children. Now as we try to repair and reimagine ourselves, Canada has more Indigenous children in care than at any other moment in history,” notes the School of Social Work’s director Sarah Todd. “In the midst of this, those of us in schools of social work need to listen to Indigenous voices and teach Indigenous ways of social working. We need to enliven, re-value, and respect Indigenous experiences.”

Professor Beth Martin, a member of the school’s decolonization and reconciliation group, has been adopting those changes in her classroom.

“I’ve started to fill gaps in my knowledge and figure out steps to take towards change, but I recognize it’s an ongoing commitment and needs to be holistic,” says Martin. “Indigenous content should not be restricted to a single required course, or a single week in a course, but woven throughout each course and the curriculum as well as in what we do outside of the classroom.”

Recognizing Community Values

For years, when social workers visited an Indigenous community, they used a checklist to assess whether children should be removed from their family. They would look for food in the kitchen or adult supervision. What the workers didn’t recognize was that these were totally different societies with their own ways of taking care of people.

“We didn’t have a refrigerator, but we always had food because we had a communal approach to taking care of everyone,” explains McGuire. “Anishinaabe women and other community members tried to provide for everyone in the community as best as they could. They knew who needed support, who had a rough winter, who didn’t have food.”

Many years later, McGuire met the social worker who had come to her community in the white car. He acknowledged that he had made mistakes and sought to make amends.

“Now Social Work is trying to do what he did: admit we did something wrong,” says McGuire. “All of these atrocities happened over generations and we need transformative change. But we can’t do it by ourselves. We need allies—people putting a hand out and saying, ‘we did this together, let’s fix it together.’ Collectives of people acting together can ensure a fairer Canada for all of us, especially Indigenous peoples.”

Todd says there’s a growing awareness among her colleagues of the need to take clear action to end colonial violence.

“We as schools of social work and professors have to speak out: until the larger issues of land claims and resource exploitation are resolved, some Indigenous communities will struggle with poverty, and social workers will continue to put Indigenous children in care for concerns that are a result of colonial violence and exploitation. We need to push for broader society to live up to the treaties that were signed and develop a respectful and justice-filled relationship with Indigenous peoples in Canada.”

Thursday, October 7, 2021 in School of Social Work

Share: Twitter, Facebook