By Karen Kelly

In the late 1980’s, the debate over the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement dominated the headlines and spurred protests across university campuses. Opponents warned of job losses, environmental destruction and a threat to Canada’s sovereignty and culture.

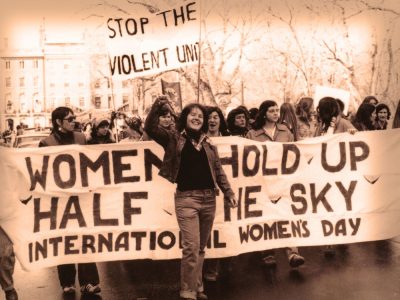

But the Canadian activists weren’t working alone. The Canada-United States FTA, which eventually became NAFTA, sparked a three-country movement of activism and protests that hasn’t been seen since.

“The NAFTA talks galvanized a wave of domestic and transnational activism across a diverse range of groups,” explains Political Science Professor Laura Macdonald, who studies North American relations. “It included labour unions, environmentalists, women, faith-based organizations, and human rights activists…who challenged the trajectory of North American integration for over a decade.”

Laura Macdonald

Twenty-six years later, U.S. President Donald Trump brought NAFTA to an abrupt end. Now, the introduction of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is giving Macdonald another chance to study the activist movement—and contrast it with the protests of the 1980s and 1990s. She recently received an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) to support her research.

“What interests me is whether the governments today are listening to civil society voices,” says Macdonald, winner of the 2018 FPA Research Excellence Award. “We’ll be looking at how these groups influence the course of trade negotiations and their relationships with each other.”

Signing ceremony for the US–Mexico-Canada Agreement in November 2018.

Macdonald is conducting interviews with activists from the NAFTA period, as well as those involved in lobbying, advocacy and protest today. Her preliminary work has found that while social media has eased communication, changes in the political landscape have undermined much of the co-operation that was once there.

“In Canada, many of these groups lost their funding under the Harper government and they don’t have the resources for sustained international collaboration anymore,” Macdonald explains. “So instead of a national coalition in every country, we have responses that are more sectoral and dispersed.”

Macdonald will explore this idea during a daylong symposium as part of FPA Research Month entitled, “Trading on New Terms: Civil Society and North American Free Trade.” She has invited scholars from both the United States and Mexico as well as Canadian civil society activists to offer their perspectives on the challenges and opportunities in the current situation. She offers a few highlights:

Canada: The Trudeau government has a so-called progressive trade agenda, but many argue not much has changed in practice.

United States: With the Trump presidency, it’s not a good moment for state-to-state relations between the three countries, but there is an opening for Canada and Mexico to increase cooperation.

Mexico: There’s been a dramatic change with the election of new president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who is much more open to concerns about labour rights, social inclusion and human rights in a way we haven’t seen before.

While activism may not be as apparent during this round of trade negotiations, Macdonald says the influence of the protest and labour movements is evident in the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

“Labour rights and environmental protections are integrated into the text. Another important thing is that Chapter 11, which allowed corporations to sue foreign governments, has been taken out of the current agreement,” she explains. “I think there are aspects of USMCA that are better than the original, although there are certainly other reasons for concern.”

Thursday, January 31, 2019 in Faculty Research, FPA Voices

Share: Twitter, Facebook