Water has increasingly become a central theme in global development discourse. Scholars have tied access to safe drinking water to a growing list of development criteria, including health, education, income generation and gender equality. There has also been a shift in the way the issue of water access and water security is discussed. Whereas technology-based initiatives and major infrastructure projects were more heavily emphasized in the past, discussions of effective governance structures based in community participation, decentralized management, and other such ‘soft’ solutions to water access issues have become more prominent in international forums.

Children play soccer on a beach in Tanzania.

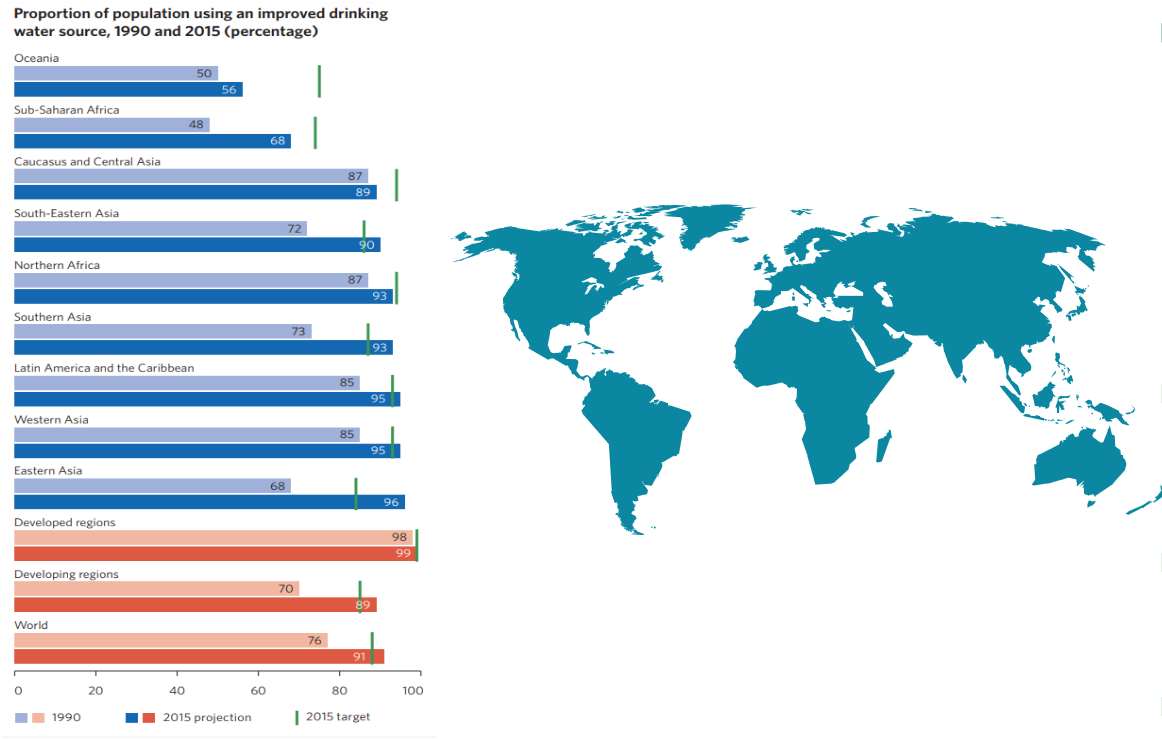

Target 7C of the Millennium Development Goals – established after the millennium summit of the United Nations in 2000 – aimed to “halve the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation” by 2015. And while this target was met globally, improvements did not occur uniformly across the globe. For the 8th installment of the Global Water Institute’s “Water Conversations” series, we heard from recent Public Affairs and Policy Management graduate Nadia Springle, whose Honours project was an analysis of the reasons why two countries (Ghana and Tanzania) which underwent similar decentralization reforms, with similar policies and institutional frameworks, and have similar climates and rainfall levels and patterns, experienced considerably different levels of improvement to water access.

This graph compares the proportion of populations using an improved drinking water source in 1990 and 2005, and the green line marks the MDG target for each region.

Nadia’s analytical framework was based on three factors that affect the performance of decentralized governance systems: power transfers, accountability, and resources.

What “power transfers” refer to:

- How power is transferred. Is it decentralized through constitutional or legislative means, or through less secure channels like ministerial decrees, administrative orders or by discretion? Is power securely held by local communities, or can it be easily taken away in the event of something such as a regime change?

- What type of power is transferred. Do lower levels of government have meaningful decision-making power and the ability to respond to local needs? Or are they simply delegated administrative tasks from higher (central) government levels?

- The strength and clarity of institutional frameworks. Are the roles of responsibilities or different actors and levels clearly defined?

Questions pertaining to local accountability

- Are local water supply organizations downwardly accountable to the communities they serve, i.e. through elections, public consultations, etc.?

- Who is receiving authority through decentralization? Is it democratically elected and representative organizations? Is it actors who are susceptible to corruption or outside interests?

How resources were defined for the purpose of Nadia’s analysis:

- Financial resources. Do local water supply systems and governments have the funding required to operate efficiently?

- Human resources (i.e. local capacity). Do people receiving power through decentralization have the necessary training or skills to fulfill their new responsibilities efficiently?

Ghana vs. Tanzania: a side by side comparison

These two countries were an ideal basis for comparison for multiple reasons:

- They have similar climates and experience similar seasonal and regional variability in rainfall.

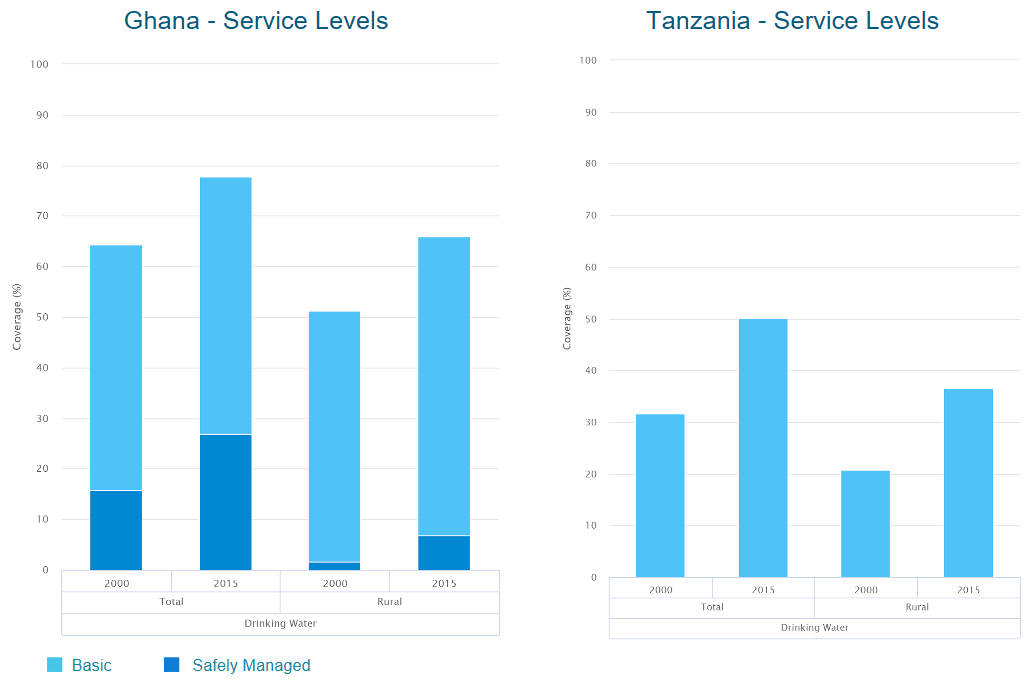

- They had similar levels of water access in 1990 – an average of 50-55% of their populations had access to improved water sources (approximately 37% in rural areas.)

- They both adopted decentralization reforms in their water sectors starting in the 1990s, and introduced National Water Policies and implementation plans that promoted decentralization in the early 2000s.

Since the 1990s, however, Ghana has consistently outperformed Tanzania in terms of water access, by 20%-30% in 2000, and again in 2015. Over the same period, in Tanzania, access levels hovered around 1990 levels.

Data from the Joint Monitoring Program run by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF.

Ghana and Tanzania adopted similar governance structures after decentralization. The institutional levels can be broken down into:

- National ministries;

- Subsector;

- District-level authorities; and

- Sub-district authorities (the community level).

In both cases, national ministries transitioned from service provision to more of a facilitator role, while service provision and management was taken on at the lower levels. The responsibilities assigned to each institutional level was also very similar in both cases. The key difference between Ghana and Tanzania’s post-decentralization structures is that Ghana has a single coordinating agency for all of its subsectors, and this agency is responsible for coordinating and implementing the rural program and distributing resources. Tanzania has no central agency; resources are distributed directly to the district level by the central government.

Both countries also performed similarly according to the analytical metrics which Nadia selected:

- The decentralization of power was secure, as it was transferred through constitutional and legislative means (national water policies). Communities were given the power to initiate, own and manage water schemes. Discretionary power was limited in both cases, with community organizations being given the power to set tariffs but seemingly being confined to set procedures and policies handed down by higher levels of government. Both countries experienced issues (albeit different issues) with the implementation of new institutional frameworks and responsibilities at the local level.

- In terms of downwards accountability, both countries have official commitments to local democracy in their water policies in theory but have experienced issues in practice, with former authorities and institutional arrangements retaining power.

- Fiscal powers were decentralized in both countries, with communities held responsible for covering the full cost of operations and maintenance for their facility, and contributing a portion of the capital costs. These funds are typically raised by collecting tariffs at water points. Neither country has received adequate financial support from other levels of government; both experienced significant funding gaps, and variations in funding amounts from year to year. In both cases, communities also experienced difficulties raising the funds to cover all their costs – a problem which raises equity concerns, because those who can’t afford to cover the costs are typically those most in need of water systems. Communities in Ghana have, however, been more successful at covering their operation and management costs than those in Tanzania.

- In terms of human resources, both countries integrated capacity building measures into their new programs and processes. Types of training might include financial management, leadership training, fundraising, maintenance of facilities, and special training for female committee members. While Tanzania also incorporated capacity building in the formation process for Water User Associations (WUAs), it has received more attention and had more success in Ghana, where there have been visible improvements. Local organizations in Tanzania continue to experience capacity problems.

Conclusions – is decentralization the issue?

Despite Ghana having higher rates of access to improved water sources, it performed very similarly to Tanzania in the areas examined, and did not significantly outperform Tanzania in the indicators for decentralization. In some cases, Tanzania outperformed Ghana. This suggests that decentralization of water governance structures is not the main factor accounting for differences in access, and such institutional reforms alone are not enough to improve access to drinking water. Furthermore, both countries experienced issues successfully implementing decentralization reforms, and more work must be done on how decentralization is actually implemented, and how it translates to lower levels.

Based on her analysis, Nadia had the following recommendations:

- Funding allocation: difficulties obtaining consistent funding levels and budget releases at the community and district level are symptoms of larger structural problems in higher levels of government. Mechanisms need to be put in place to improve accountability and equity.

- Ways to improve fee collection need to be explored, as many communities are experiencing difficulties, or collecting fees inconsistently. At the same time, cost recovery and capital contributions must be balanced with equity concerns in order to avoid further disadvantaging already struggling areas. Potential solutions include introducing incentive structures, and subsidizing poor and underserved areas.

- Finally, capacity building efforts must be improved. More follow-up is required to help identify best practices, and ensure that training is translating into better outcomes. Furthermore, not all district or community organizations clearly understand their roles and rights – education about new institutional arrangements needs to be improved.

Article by Christiane Mineau.