By Lesley Barry

Kati Morrison was four years old when her grandmother pulled her and her year-old sister into the dimness of a stairwell and saved their lives. The three waited silently while the other 100 or so residents of the building – neighbours, friends, Kati’s great aunt – were marched away to the edge of the Danube, methodically lined up and shot. It was January 1945 in Budapest, Hungary and the Second World War and its black shadow, the Holocaust, had four murderous months left to run.

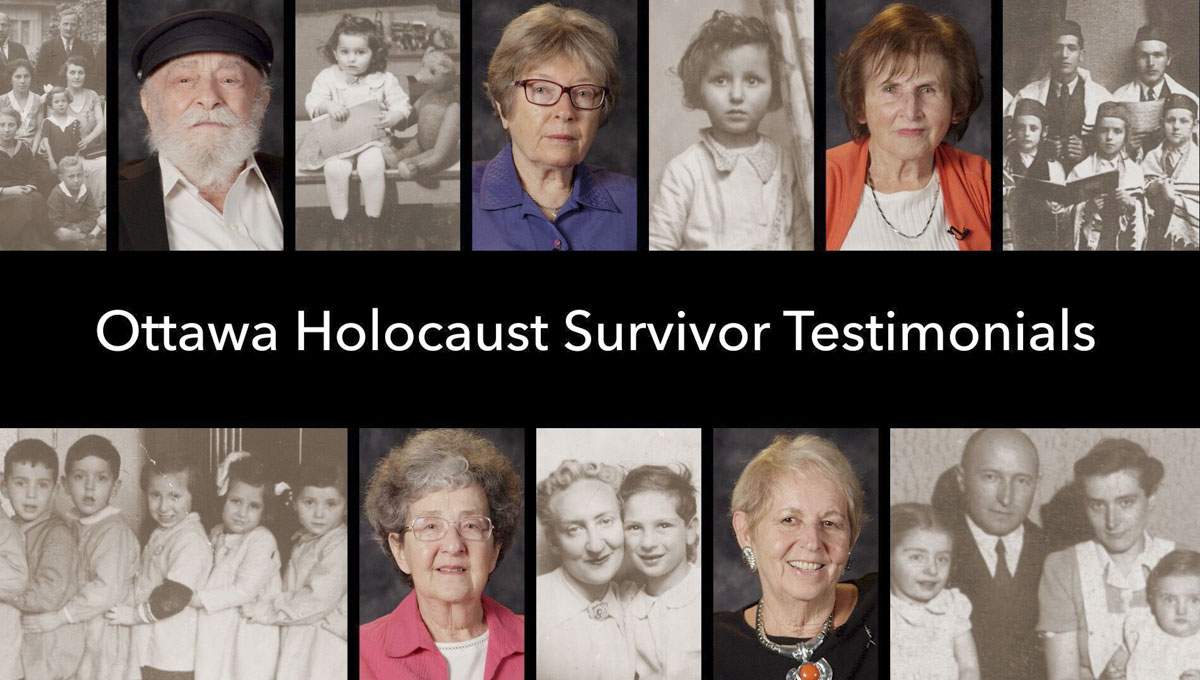

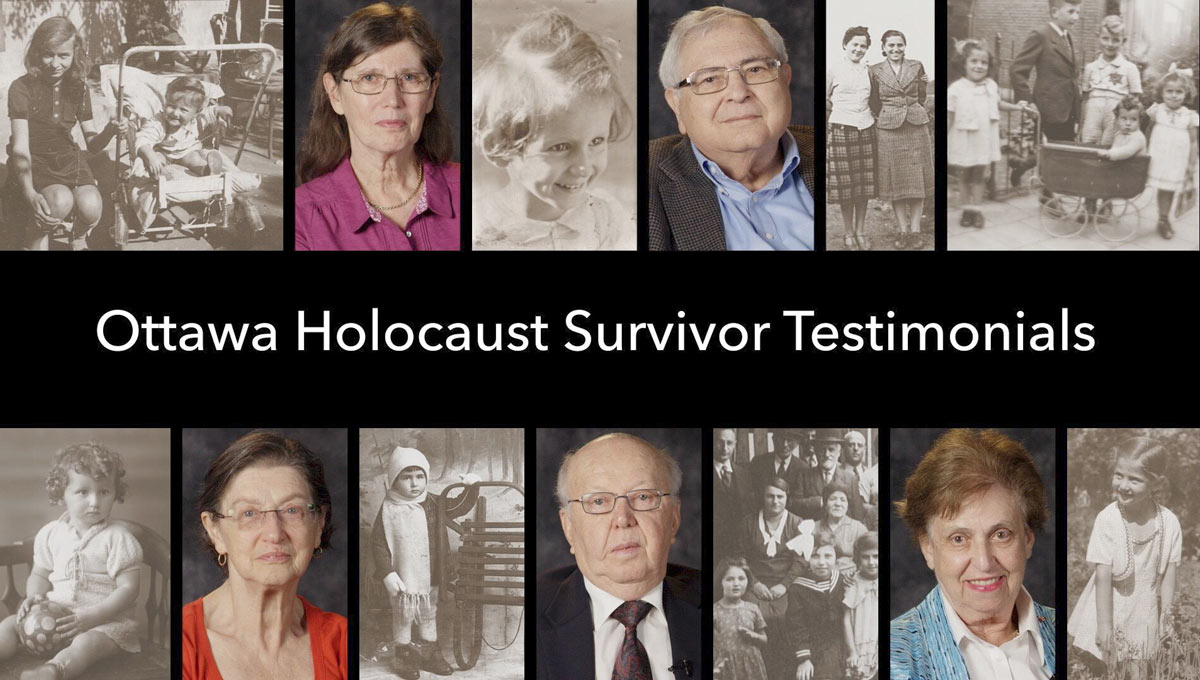

This chilling incident is part of Morrison’s story of surviving the Holocaust, which she tells with calm dignity. She has told it to countless students in the Ottawa area over the last 12 years, and now it is captured on film and available online as one of a collection of 10 stories that make up the Ottawa Holocaust Survivors Testimony Project.

Shoes on the Danube Bank is a memorial in Budapest to honor the people (mostly Jews) who were killed by the fascist Arrow Cross militiamen in Budapest during World War II. Jewish people, like Morrison’s great aunt, were marched away to the edge of the Danube, methodically lined up and shot.

“There is nothing more powerful than first-hand testimony,” says Mina Cohn, director of Carleton’s Centre for Holocaust Education and Scholarship (CHES), which organized the initiative after opening as Ottawa’s first Holocaust centre in 2015.

The Importance of Remembrance

The impetus was the dwindling number of Holocaust survivors.

“Most of those who were adults in 1939, when the war started, are very old or no longer with us,” says Cohn.

“We needed to find a way to preserve the stories of the remaining survivors in the Ottawa area.”

The 10 testimonies, each of which covers life before, during and after the war, as well as survivor perspectives on the importance of remembrance, present a range of experiences, from working amid atrocities in Nazi concentration camps to hiding in a dugout in Ukraine for two years. The oldest participant was 17 at the start of the war, and the youngest was a baby.

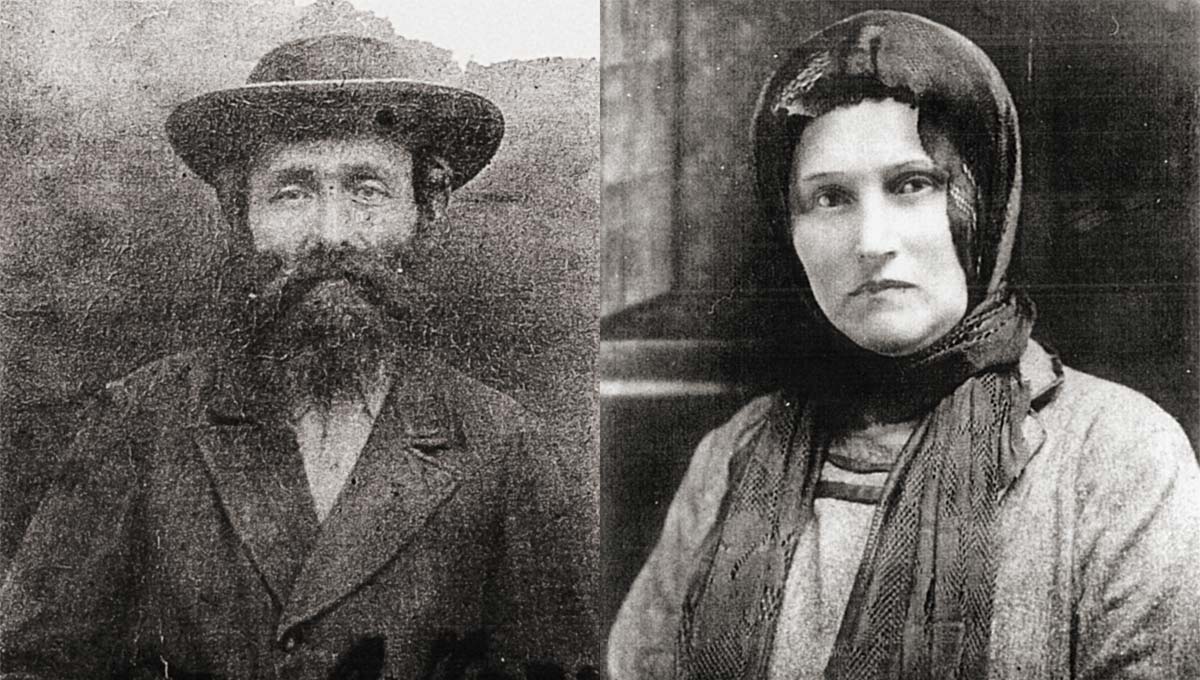

Morrison’s paternal grandparents, Jozsef and Hani Fisch, aged 64, were transported to Auschwitz. Both died en route: her grandmother had a stroke and was thrown off the cattle car. Her grandfather jumped after her, and was immediately shot.

The films, which were crafted to industry standards at Carleton’s Media Production Centre, were edited to about 30 minutes to ensure sufficient time for class discussion; two-minute excerpts are also available for quick review. In the project’s next phase, the CHES committee is developing resources for each film that will also be available online. They also offer a teachers’ workshop. The response from area institutions and schools, Cohn reports, has been encouraging.

Researchers and historians, meanwhile, can find the 10 hours of original, unedited interviews in the archives of Carleton’s MacOdrum Library.

An Important Resource for Research

“My hope is that the university will promote this valuable, authentic primary research material,” says Cohn.

Annette Wildgoose was a volunteer for the project, which was completed on a shoestring budget that was crowdfunded on Carleton’s FutureFunder platform. She got involved for personal reasons: her mother was a Holocaust survivor and Wildgoose left it too late to talk to her about what happened.

“I wish I had asked more questions. Her story was important to what remains of our family.”

Wildgoose’s role was to conduct pre-interviews with Morrison and with another survivor, Elly Bollegraaf. She was more nervous than they were and she remains in awe of their strength.

“It takes guts to relive those stories. They are remarkable people and demonstrate, in person and on video, tremendous resilience. But they know that if they don’t speak about this, no one else will.”

The foyer of the ‘safe house’ that Morrison and members of her family stayed in during the war.

Morrison, who emigrated to Canada in 1967 and worked as a psychiatrist, continues to visit schools. “It’s worth the price. The children are very attentive and thoughtful.”

She, in turn, is inspired by educators who teach how to raise children who will speak out when others are being bullied or intimidated and stand up against intolerance and prejudice, regardless of peer pressure.

“I go to the schools to help students understand that there is no such thing as a silent bystander. Everyone who allows cruelty to take place is a participant.”

All three women see a new timeliness for the Holocaust testimonies in today’s political climate. As Wildgoose says: “When we know what happened when racism and violence took over, we learn to be kinder to one other. We learn not to turn our backs.”

Watch the two-minute excerpts and full-length films.

Click here to view the Carleton FutureFunder page for this project.