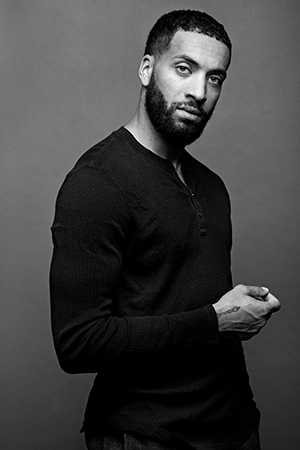

By Nathanial Behar-Walker

Photos by Martin Lipman and Chris Roussakis

I was born for the second time on September 20, 2014. In a faux grass colosseum, with five seconds remaining in what would go on to define much of what I am, or was, quarterback Jesse Mills heaved an oblong piece of leather into the sky and Lady Luck stretched my arms low to catch it. As one-twelfth of the offensive unit on the Carleton Ravens football team, we did the improbable — winning the annual Panda Game against our rivals at the University of Ottawa in a dramatic dying seconds comeback — and my new identity took shape. Nate Behar was a football star now. A boisterous and arrogant one. It was not a complex role to assume, nor a mask I ever struggled to don.

If that game was my birth, then the 2017 CFL draft was my high-school graduation. Selected fifth overall by Edmonton, I spent two years playing wide receiver out west. Then came free agency and I returned to Ottawa, proud and excited, to join the RedBlacks. Yet 2020 has chosen a new path for us all. Like so many on this planet, my livelihood has been put on pause while we recoil and recover as a society from the ongoing earthquake that is COVID-19. A football player with no season on the horizon. So who am I?

The first time I was born, it was to an Israeli mother and a Jamaican father in London, Ontario. I was darker than the vast majority of my city. Vast majority. My father had the mind and soul of an artist; my mother had the heart and capacity for love of a goddess. But as we all know, that’s not always enough. So she raised me in London, and he coached me on from Toronto. I started football at age six, enthused and motivated. Then it happened.

Nathanial Behar-Walker

I was taught as a nine-year-old how Black athletes are seen. I learned from four opponents my age one brisk evening, on the field that until then had been my safe place, that the answer is a nigger. They taught me with loud voices and wry smiles, surrounding me and thrusting the word deep into my heart, to ensure that time wouldn’t soften the jagged edge of their dagger. So how then are the Black men and women of sport to see themselves in a society absent of their sport? A society that puts its knee to the throat of those who look like you, a society that lets you die disproportionately in the hands of health-care workers, a society that locks you away quicker, for less, over and over again. Who can we be when, even while thousands cheer us on, we strain to feel valued past the price of admission? There’s no single blanketing answer, because we are not a hegemonic people. But the one clear answer is that we cannot be silent.

The third time I was born was a long and laborious delivery. The birth certificate reads June 2020, but conception occurred over years of experienced microaggressions, macroaggressions and the online murder-porn stream of Black bodies. Without the physical and emotional outlet of football to bury my head into — a coping mechanism I’m embarrassed to admit I’ve used too often — I saw that silence was no longer an option. As the child of an artist and a goddess, I began to respond the only way I knew how. With words. Sometimes in this form, written in editor-unfriendly run-on sentences, and sometimes in poetry.

No person of a subjugated race wants to grow into an expert on race due to their own subjugation. But as we’ve all been taught in 2020, the universe does not care one iota for what you do or do not want.

This is who I am now. Outspoken and unapologetically me, which is to say unapologetically Black. But not a day goes by that I don’t miss the boy who lived for nine peaceful years unaware that he was seen as less to some for his pigment. And every day, I look forward to the time where all three of me can exist together — looking on at a world that accepts and values me, screaming in joy in my safe space on the field, and writing about a society that invests its energy into love and creativity. But until then, I write in the face of the storm we collectively stare into, as 2020 tests us again and again. Reborn.

Tuesday, November 24, 2020 in Short Reads - Fall 2020

Share: Twitter, Facebook