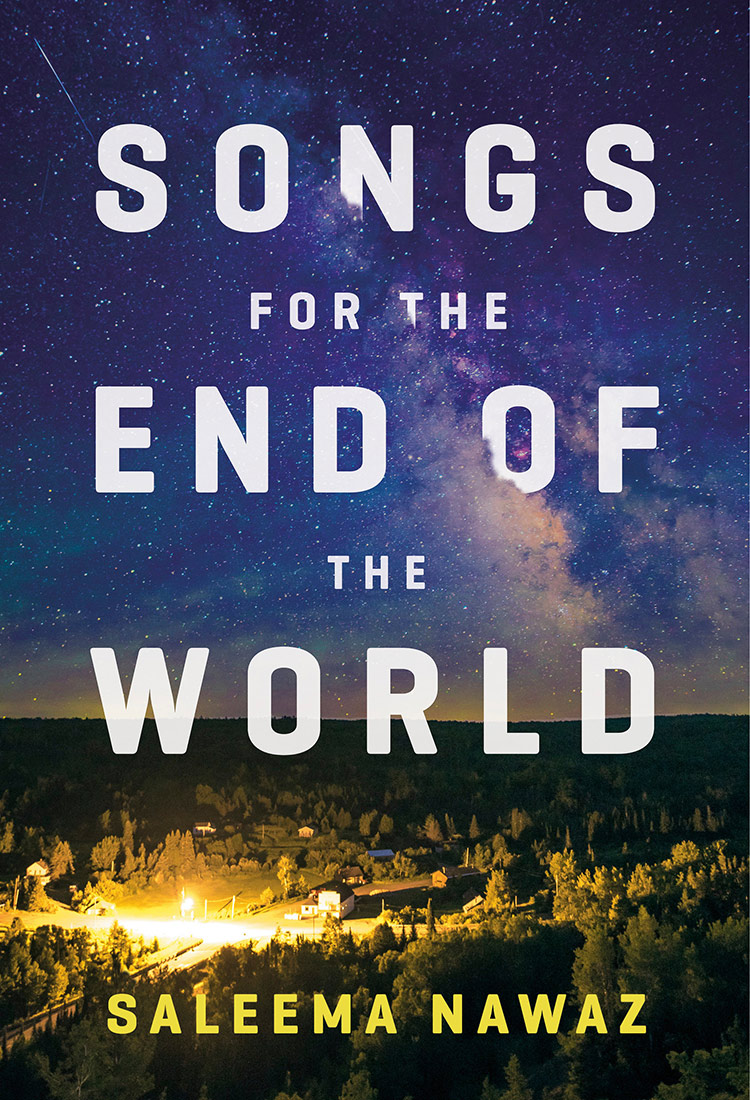

Reality Fiction: Carleton alumnus Saleema Nawaz’s new novel eerily predicts the pandemic

It was ten minutes before the start of his shift and Elliot was hungry. Half of the businesses in Washington Heights had shut down in early October, but the restaurant closures were the biggest pain in the ass. Elliot had been forced to revive cooking skills he’d repressed since college: scrambled eggs, pasta, sloppy joes. There was a booming commerce in food delivery for intrepid couriers, but sitting and waiting at home reminded him too much of his quarantine. Now even the grocery aisle at the drugstore was picked over. He leaned down to inspect a lone instant ramen bowl on the bottom shelf while a woman in a purple raincoat edged over to move away from him. He noticed she had peanut butter and pickles in her basket, and his stomach spasmed.

The centre display of Halloween candy at the front of the store was the one thing left untouched. Usually there’d be slim pickings the day after Halloween, but this year the mayor had called off trick-or-treating — just in case there was anyone living under a rock somewhere who still wanted their kids to go door to door in the midst of a pandemic.

Elliot grabbed a fifty-piece variety box with Kit Kats and Milk Duds. Better to get fat than to starve.

Bryce loved Kit Kats. Elliot’s partner had come down with ARAMIS [Acute Respiratory and Muscular Inflammatory Syndrome] after they’d worked a quarantine relief shift at a big apartment building with sixty confirmed cases. Quarantine relief was a constantly evolving role that entailed food delivery, warning off visitors, and, increasingly, issuing tickets to people registered under a Q-notice who refused to stay home. Though quarantining was technically still voluntary, the city’s top medical advisors had recommended enforcement given the long incubation period of the virus. For police officers like Elliot, this meant trying to strike a delicate balance between respecting the personal liberty of thousands, and guarding against the potential damage that could be wrought by a single infected individual on an ordinary day. What happened to Bryce was a reminder of how badly — and easily — things could go wrong. A feverish, stir-crazy woman adamant on leaving the building had pulled off his mask and coughed in his face to prove she wasn’t infected. Forty-eight hours later, Elliot had watched as her body was carried out in a biohazard bag, while Bryce stayed home under his own Q-notice. A week later, he was symptomatic. Public visiting hours at all hospitals had been suspended, although according to the latest daily update from Bryce’s wife, he was still conscious but breathing with a ventilator.

The self-checkout kiosk was slow; in the store’s far corner, an idle cashier blinked up at a wall-mounted television blaring ongoing coverage of the deadly aftermath of the big fundraising concert in Vancouver. Even when people were trying to do the right thing, Elliot thought, things could still go spectacularly wrong. He stood well back from the person ahead of him in line. It was no longer considered polite to get closer than three feet of someone, though it made for some unruly queues that nettled his sense of public order. Behind him, there was a scraggly row of gloved and masked customers extending all the way into the shampoo aisle.

Everyone in line, Elliot realized, looked like they were steeling themselves for the worst.

Excerpted from a chapter set in November 2020 in Songs for the End of the World by Saleema Nawaz. Copyright © 2020 by Saleema Nawaz. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Looking in the Mirror

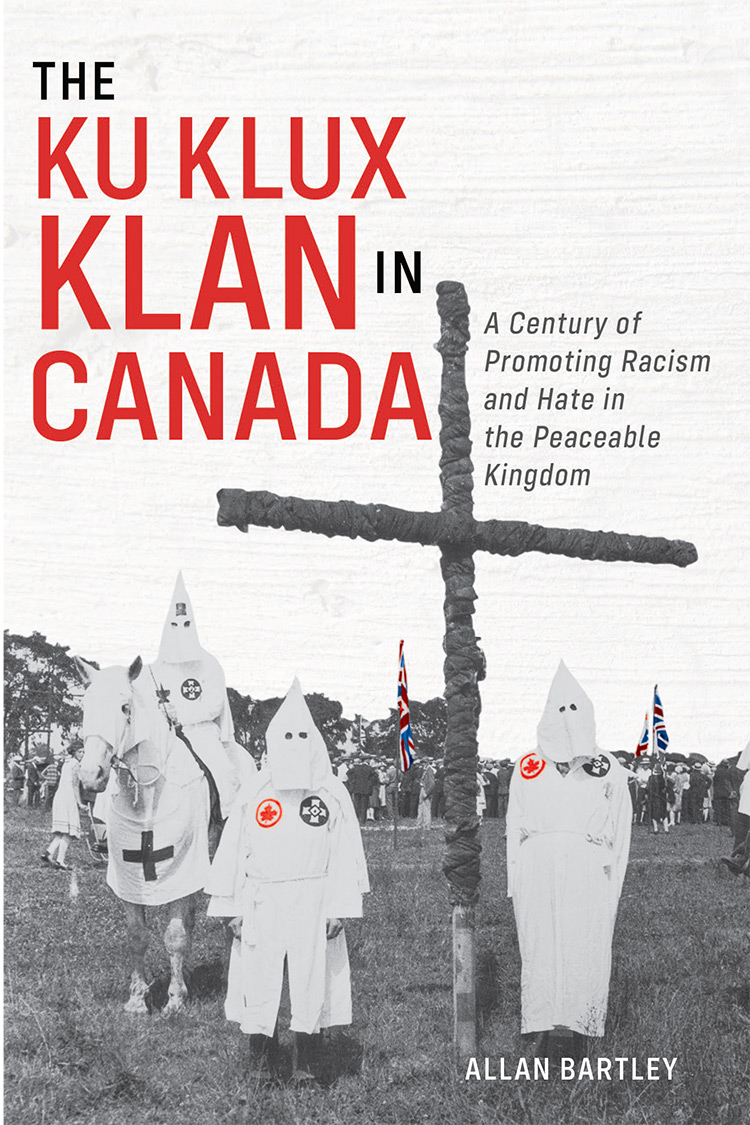

Hate has a name. Hate has a face. Hate has an address. It lives in Canada. The Ku Klux Klan’s more than one-hundred-year presence in Canada demonstrates how hate lived and flourished and still endures in the nation sometimes known as the Peaceable Kingdom. Our neighbours were partly to blame, but Canadians can also blame themselves.

“Because we believe that it can’t happen here, we are too hesitant to talk about the way in which some people — and politicians — are already admiring the reflection they see when they look south,” novelist Alexi Zentner wrote in the Globe and Mail in the summer of 2019. “We think of virulent hatred as a thing that comes from the history books. And yet, the history books are coming to life again.”

The challenges of writing a book on the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Canada go beyond creating a narrative. There is the concern that to write about hate is to condone it. To write about the leaders and their followers runs the risk of glorifying them or ridiculing them or magnifying or minimizing their ideas and impact. The odious reality of the Ku Klux Klan and its imitators over the decades speaks for itself. We need to confront that reality.

From the preface of The Ku Klux Klan in Canada: A Century of Promoting Racism and Hate in the Peaceable Kingdom (Formac Publishing, 2020), by Allan Bartley, an adjunct political science professor at Carleton.

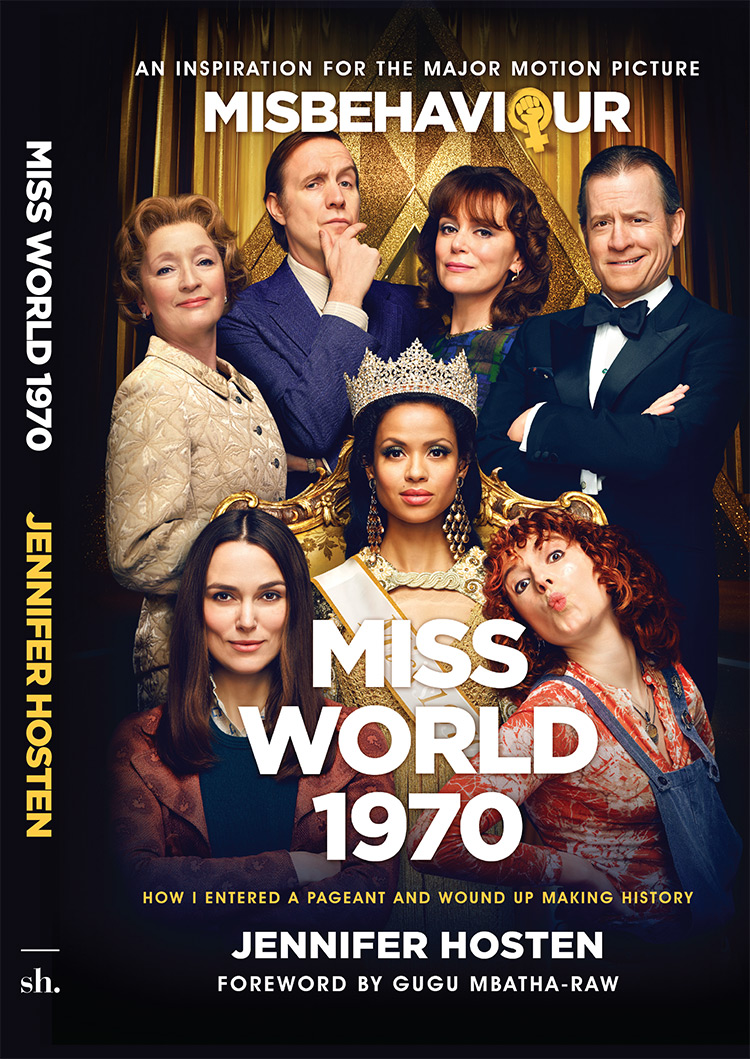

Breaking Barriers

My master’s thesis, on the effect of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), between Canada, the United States and Mexico, on Commonwealth countries in the Caribbean, was published in book form, which is how my friends in Grenada found it. My goal in all this effort was a worthwhile and stable career with the government of Canada, and particularly its international development agency (CIDA). Before I could apply for work in international development, I was persuaded by another branch of the Canadian government to manage an anti-racism campaign, which I did for three years in the early 1990s. I then turned my attention to the field in which I was trained, joining CIDA and working on environmental projects in several developing countries, including Eritrea, Ethiopia, India and Thailand.

While there, I was approached by Caricom (short for Caribbean Community) consultants who were formulating options for dealing with NAFTA’s impact on the islands. There was anxiety among English-speaking Caribbean nations that they would be left out in the cold as North America consolidated its trade. My thesis had argued that the appropriate response for the Caribbean region was to integrate its own trade. Otherwise, it would always be waiting for handouts from so-called developed countries. The issue was right up my alley.

From Miss World 1970: How I Entered a Pageant and Wound Up Making History (Southerland House, 2020), by Jennifer Hosten — the first Black woman to win the Miss World Title, who later served as Grenada’s High Commissioner to Canada and earned a master’s degree in political science at Carleton.

Tuesday, November 24, 2020 in Short Reads - Fall 2020

Share: Twitter, Facebook