Carleton is home to a diverse population of students and professors, many of whom have moved to Canada from abroad and made this university a key stop on their journeys. They enrich our public service, business practices and international relations, bring vitality to our arts and strive to give back in profound ways.

- Diversity Matters: Zahraa Al-Ahmad’s Refugee Research

- Chancellor Yaprak Baltacioğlu’s Fresh Start

- Security Scholar Stephen Saideman Thinks Beyond Tomorrow

- Business Dean Dana Brown’s Conscientious Capitalism

- Home: Novelist Kagiso Lesego Molope Finds the Right Words

- PhD Student Akintunde Akinleye Looks at the World Through a New Lens

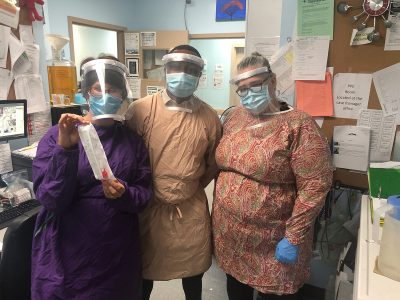

Diversity Matters

By Lisa Gregoire

Photos by Rémi Thériault

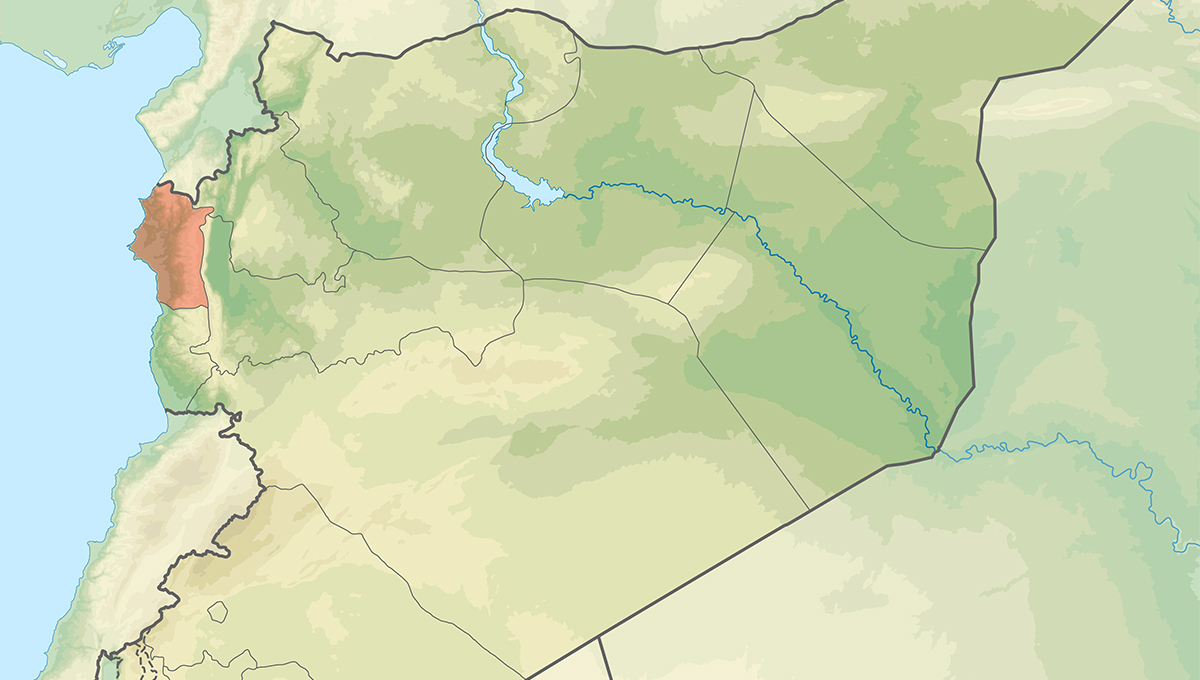

Last July, Zahraa Al-Ahmad was in Beirut, Lebanon, ready to begin a research project focusing on the educational and employment barriers faced by Syrian refugees in that small country pinched between Syria and Israel on the Mediterranean Sea. But after several weeks abroad, she was still facing her own barriers — logistical and bureaucratic delays that prevented her and a Lebanese colleague from conducting interviews with refugees. So she sat, spinning her wheels, frustrated and worried that she was squandering a precious opportunity to better understand, and possibly even improve, the experience of several hundred thousand Syrians in Lebanon.

If you think those wheels spun for long, you don’t know this woman.

Al-Ahmad, a Syrian-born political science graduate student at Carleton, is one of the first student researchers with the Local Engagement Refugee Research Network (LERRN), a seven-year Canadian initiative which helps partner universities in Lebanon, Jordan, Tanzania and Kenya conduct homegrown research projects that are relevant and meaningful to them. Al-Ahmad is, by her own admission, a shy and introverted 23-year-old who makes a mean lasagna and prefers board games with friends to late-night parties. But here’s what others notice: intelligence, confidence, resourcefulness and quiet tenacity, all of which come in handy when trying to work in a foreign country — especially a complicated place like Lebanon.

Syria and Lebanon have a contentious history. Lebanon’s 15-year civil war, which started in 1976, led to significant Syrian intervention that lasted until 2006. After that, Lebanon tried hard to rebuild from chaos within a region dogged by perennial conflict. Then, in 2011, Syria deteriorated into civil war itself, sending its citizens fleeing, many into Lebanon.

Census data are imprecise but it’s estimated that about one in three people in Lebanon is a refugee, predominantly Syrian and Palestinian. Lebanon’s estimated population of 6.1 million people includes roughly 1.5 million Syrians and 500,000 Palestinians, which means that Lebanon is home to the highest per capita refugee population in the world. Many educated Lebanese can’t find jobs and resent newcomers. With no official refugee camps, Syrians face a precarious legal status and fickle restrictions on where they can live and which jobs they can do.

Despite project setbacks, Al-Ahmad was still hoping to find out why Syrian refugees weren’t going to school or getting jobs. So after conferring with LERRN project director James Milner, a political science professor at Carleton, Al-Ahmad switched gears halfway through her six-week trip, made a list of relevant non-governmental agencies (NGOs) and put her first language — Arabic — to use.

She tracked down busy NGO staffers, charmed her way into last-minute interviews and took Ubers across the city to streets with no addresses and only vague instructions: it’s across from the market; text me when you arrive and I’ll come find you. The work was stressful and tiring but also relevant and fulfilling. And it was better than spinning her wheels. “There was a learning curve, but honestly, it was a great experience and I’m so thankful for it,” Al-Ahmad says over tea on the Carleton campus.

“It was a lot of work and a lot of pressure, but I wanted to get the most I could out of my trip.”

Before flying home, she presented her findings to the LERRN team in Lebanon, including suggestions regarding structure, logistics and limitations to help streamline future research in the region — paying it forward for her colleagues there and back home in Canada.

Diversity and Positive Change

That’s the kind of flexibility and professionalism LERRN needs in its student participants, says Milner, who praises Al-Ahmad for her grace under pressure. “These trans-national research partnerships, working across context and capacities, they’re wonderful when they go well, but they’re really tested when we encounter these kinds of challenges,” he says. “That’s where the trust and dialogue that we create help us problem solve and find ways toward positive outcomes. I felt so fortunate that Zahraa was there because of her ability to do those things.”

Al-Ahmad’s ability to overcome challenges and accomplish something worthwhile is second nature for a girl who grew up in a new Canadian family. She moved to Toronto from the thriving port city of Latakia, Syria, with her parents and two older brothers in 2005 when she was eight. They lived briefly in North York then moved to Etobicoke, watching English TV to learn the language but speaking Arabic to one another. Her father is a civil engineer and her mother, an early childhood educator. Both returned to school in Canada to get re-certified, working day and night at their studies and placements. It was a challenging few years during which her brothers stepped up to help take care of her.

Canada offered myriad opportunities but it was not Syria. Winters were cold and clothing was thick and heavy and, as a child, Al-Ahmad felt like a total outsider. She missed the olive groves of home, the Mediterranean beaches and her many cousins, aunts and uncles, but she saw in her parents a recipe for success: hard work, love and persistence.

The Al-Ahmads were not refugees and their move was supposed to last only until the children had finished school and university. Then their country fell apart and Canada became home. Syria’s civil war, which has killed more than 100,000 civilians and displaced millions of others, has spared coastal Latakia. But the country remains in tatters and more than 25,000 government-sponsored Syrian refugees have come to Canada and thousands of others through private and group sponsorships.

The Pull of Politics

Zahraa loved talking politics in her family’s Etobicoke home, but like many loyal children of immigrant parents, she wanted to be a doctor. To that end, she started attending Toronto’s York University as a science undergrad and, for fun, took an arts elective. Then she discovered that one could actually get a degree in a different kind of science: the political kind. She switched majors and earned a bachelor’s degree in political science in 2018.

Thinking that the nation’s capital was a good place to continue studying politics, Al-Ahmad applied to do a master’s degree at Carleton. One of her courses was in the global politics of migration with Milner. Most refugees live in the global south, Milner says, but most refugee research is controlled by the developed world, where there is money and influence. LERRN is trying to change that dynamic by offering expertise, funding and capacity. Refugee host countries direct the projects while Canadian researchers act as partners and amplifiers.

When it was time to recruit LERRN’s first cohort of student researchers, Milner thought that Al-Ahmad, with her background, political interests and language skills, would be an ideal fit. He was right. Carleton touts diversity as an asset and that’s not just words, he says. “There is an untapped strength at Carleton: the backgrounds and the life journeys that students bring with them,” says Milner.

“Everyone in the Carleton community has come from a journey and the more we embrace that journey, the more we’ll be able to realize the real social purpose of the university — to engage in real-world problems, not just in an efficient way, but in a very respectful way.”

Al-Ahmad expects to earn her master’s in April 2020 and then it’s on to a PhD. At this point she’s considering a focus on security studies. So, her plans of being a doctor might still pan out, just not a medical one. And her parents support that. “I think they knew that no matter what I was studying, I would work hard,” she says. “I’m not somebody who stands as life goes by. I want to help Syria and Syrians because they’re such a big part of my identity as a proud Syrian-Canadian. That’s why this work is so important to me.”

Chancellor Yaprak Baltacioğlu’s Fresh Start

As told to David McGuffin

Yaprak Baltacioğlu’s journey toward becoming Carleton’s chancellor in 2019 contains many valuable lessons. Originally from Turkey, Baltacioğlu, in a 29-year career in Canada’s civil service, rose to become the highest- ranking immigrant in the federal government. She spent 15 of those years as a deputy minister at Treasury Board and the Agriculture department, among other appointments, championing efforts that advanced mental health, employee wellness and workplace diversity. The advice she gives new Canadians is to carefully study where the opportunities are. “There’s a huge commitment to diversity in the federal public service, making sure we represent Canada,” she says. “The numbers for women and minorities are much higher than in the private sector.”

A master’s degree graduate from Carleton’s School of Public Policy and Administration, Baltacioğlu was born into a prominent family, the only child of one of Turkey’s top civil rights lawyers and an artist mother. “It was a tough marriage,” she recalls. “They just couldn’t ever get together.” In a way, this prepared her for the roles she played as a senior public servant: “I have capacity to mediate almost all conflict. I was very well trained in trying to make sure nobody fights.”

My mother was a wonderful artist. She loved animals. She loved people. She was generous. I didn’t know she had depression. In 1980, she killed herself. It’s going to be 40 years and … when I talk about it, it still chokes me up. That was the year I moved. She died in February and we came to Canada in August, which was amazingly good for me. A fresh start is the best thing to do. Just change. Change climate, change culture, change history. Nobody knew me. Nobody knew about me. It was pretty public in Turkey when my mother died.

As an immigrant, if you don’t have Canadian work experience, if you don’t have Canadian credentials, and if you don’t have any contacts, finding a job in any professional area is hard. So I applied to Carleton. That was the beginning. First it gave me the education and the credentials. It gave me the contacts through my professors and classmates who ended up becoming accomplished in public policy. And it also gave me the confidence that I was actually capable.

Coming to Carleton helped me find my first job in the civil service in 1989. I looked for interesting places to work and good people to work for. In the mid-1990s, I became chief of staff to the Deputy Minister of Agriculture just as deep budget cuts were being implemented. Huge subsidy programs like the Western Grain Transportation Act were repealed, and I got to see how a big organization changes shape. Our minister was Ralph Goodale, the MP from Saskatchewan, and those cuts were hard for a western leader to make. I watched everything he did and how he handled challenges, from weighing options to communications to basic survival. That was the best training you can get.

Despite all the support I had from colleagues throughout my career, I didn’t talk about my mother’s suicide because of the stigma. Then, five years ago, I heard that some of my employees who had children with mental health issues were not telling anybody and were trying to take time off to care for their families, and I started thinking, “God, we’re in the 2000s and we’re still not talking about it?” So I gave a speech about my mother to 600 executives. It’s personal, but it was important that I spoke out because I was a senior person in the federal government. The stigma is not going to go away unless we talk about mental health.

It’s important that Carleton and other universities are so focused on these issues today. Carleton has made a major difference to me; if I hadn’t gone to school here, I don’t know what my life would have been. Which is why, when the university asked me to become chancellor, I immediately said yes. You don’t always get to pay back. I’m lucky that I can.

Security Scholar Stephen Saideman Thinks Beyond Tomorrow

As told to David McGuffin

Last summer, Stephen Saideman, a professor at Carleton’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, received a $2.5-million partnership grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for the Canadian Defence and Security Network. Launched in spring 2019, the network brings together more than 30 partners, including government agencies and civil society groups, to address the security challenges facing Canada and figure out how best to address these threats. “We need to reduce barriers between the academic world, the policy world and the public,” says Saideman, its director, “and there’s support for that in Canada.”

A dual Canadian-American citizen originally from Philadelphia, Saideman came to Carleton in 2012 from McGill, where he had started teaching a year after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. That day, he was working as a Council on Foreign Relations Fellow with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon, focused on rebuilding the Balkans and other post-Cold War international fine-tuning. That focus would change completely for Saideman — and the world — by day’s end.

I was in the Pentagon when the towers in New York got hit. An Air Force colonel came in and told us to turn on our TV. We saw the second plane hit, and it was pretty clear that this wasn’t an accident. Right after that I had a meeting with the State Department about Bosnia. At that point, we could still see planes taking off and landing at National Airport, which is next to the Pentagon. Then, while we were driving on the bridge between Arlington, Virginia, and downtown Washington, D.C., I heard a noise. I turned around and saw smoke behind me — that was when the plane hit the Pentagon. I got on my cellphone, called my wife and said, “Don’t worry about me.” She said, “Why should I worry about you? You’re not in New York.” So I told her what happened.

We went back to the Pentagon. It’s an enormous building and the plane had hit the opposite side, so we were able to get back in. But the building was on fire. That day, the United States changed from a place that was trying to be involved in the world in ways that weren’t particularly risky to a country at war.

It was really strange to watch America go to war while teaching in Montreal. There were two distinct wars: the Afghanistan war, which felt like it was pushed upon the U.S., and the Iraq war, which was a war of choice — a war that was ill-considered both in terms of how it started and how it was implemented. I worked in the Pentagon when it was being run by Donald Rumsfeld, the Secretary of Defence, and was pretty skeptical about the ability of his people to do the right thing. It was embarrassing as an American to be living in Canada at a time when the United States was doing something so, so wrong.

I liked the idea of moving to a place like Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, where the main job is to train the next generation of people who will work in government. I felt that I’d have more opportunities at Carleton to teach people who would be going into the policy world. As a scholar of international relations, it’s exciting to be in the national capital. I’ve had the chance to have lots of conversations with colonels and generals, with people up and down the ranks of Global Affairs, which has helped us build the new Canadian Defence and Security Network. Canada’s place in the world is shifting and the government is consumed by the day-to-day, but we academics have longer time horizons and can help think beyond tomorrow.

I think what makes Canada special compared to many other countries is how we welcome immigrants. That allows us to have more creativity and more innovation — and better food — than other countries. It allows us to be less chained to narrow perspectives, which means we do things better on a whole than other places because we have a broader imagination.

Business Dean Dana Brown’s Conscientious Capitalism

As told to David McGuffin

Dana Brown, the new dean of Carleton’s Sprott School of Business, has spent much of her career navigating uncertainty. That’s where she’s most comfortable. “I don’t need to have the answer,” she says, “and I think it’s good to experiment, to try things and see whether they work.”

Born and raised in the U.S. and a longtime resident of the U.K., Brown arrived in Ottawa last summer with her husband and three children and an impressive track record: director of the University of Oxford’s MBA program; dean of Business and Law at De Montfort University in Leicester, England; a professorship at the EMLYON Business School in France and a visiting lecturer at the American University in Cairo. But her trajectory in academia and business hasn’t followed a traditional route. She earned a master’s in Eastern European Studies at Oxford and a PhD in Political Science at MIT in Boston, and was one of the first few dozen employees hired by Jeff Bezos at Amazon, none of whom had a background in business or retail.

At Amazon, we were a bunch of young people who knew very little about business, trying to figure out how to make this new thing work, and I think that was part of Jeff ’s strategy. He wanted to build something different and he didn’t want preconceived ideas about how things were done or what was possible.

I think my fascination with change in business goes back even earlier, however, to when I was an undergraduate political science student at Rutgers in New Jersey and spent a year abroad in Moscow. My time there coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of communist-era economic planning. It was like a Wild West market in Russia. Nobody knew who was calling the shots. Price reforms and subsidies had been in place but were stopping. Rents and heating costs were spiking, and people were losing their economic foundations. People were on the streets selling everything they owned, even their toothbrushes.

Later, I got a job in Moscow with an American construction firm that was building a development in the centre of the city. They had hired Russian construction workers and brought in materials from Europe. My job was to manage the inventory because workers were constantly taking toilet seats home. There were no toilet seats left — Russians typically didn’t have access to such things — and workers were walking off the site with everything. My job was to basically manage this process, and people were not happy when I told them they couldn’t leave with toilet seats.

My experience in Russia and Eastern Europe really made me think about how to conscientiously build a capitalism that works for people. That led to my first job as a professor at Oxford. I was asked to come to the business school by the dean, who wanted to find a way of teaching future businesspeople to think differently about economic development and investment — to think about an approach that wasn’t just about exploitation of the environment and low-cost labour and taking advantage of weak regulations. The status quo is basically a stripping of assets, which is where we are today, in my view.

I was interested in Carleton because I like to go places where there’s an opportunity to really build something. Carleton is in this mode and is thinking about its footprint and impact. That attracted me to this new role. When the job offer came, I had a teenager and we were established in England. It’s where our kids had grown up, and we had Europe at our fingertips. The idea of moving to Canada was a bit scary for everybody. But Brexit kind of pulled the rug out from under us. If you’re raising a family and thinking about future opportunities, Canada is a good place to be. I want to know what’s going on in the world, to have an impact and be engaged in meaningful work. But I don’t want my kids to be worried all the time. So Canada and Carleton made sense.

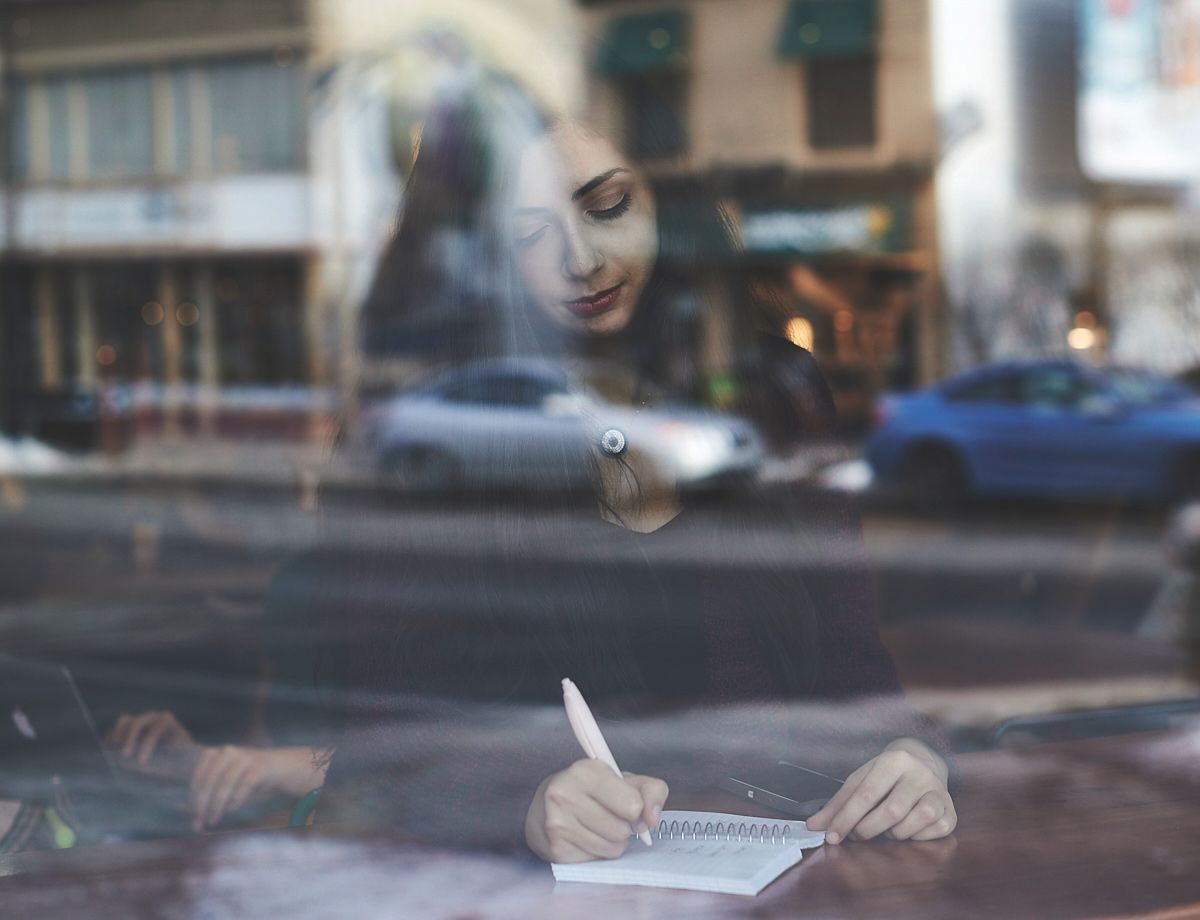

Home

A Novelist Finally Finds the Right Words

By Kagiso Lesego Molope

The first time I discovered that I could travel without my body moving was during a government-imposed state of emergency in my quiet South African township in the late 1980s. Night was falling and so were bullets, outside and all around us. We were forbidden from leaving our homes and I was in my small bedroom with my two younger sisters and three visiting friends who could not leave because they had stayed out past curfew. We were listening to bootleg tapes of rap music that was so defiant I knew it had to be illegal.

I want to say it was the rhythm of the song coming from the small tape player that moved me, but really, it was the lyrics, the way they transported me from the confines of that room to another land. In my mind I travelled to and lived, briefly, in a place that felt like freedom. I knew then that I wouldn’t spend my adult years in the country where I was born.

People always ask: Where is home? It’s such a heavy question. Whenever I’m asked, I fumble my way through an answer and come away thinking that I sound terribly inarticulate. But the truth is that it has taken me a couple decades to come to what feels like the right response.

I am a professional storyteller, a novelist. I believe it is my ability to travel to other worlds that has held me together through the very long process of settling in Canada and becoming comfortable with a language so far removed from my mother tongue. From the very beginning of arriving here in 1997, I sought solace in writing. I found these words in a collection of stories I wrote in my first few months in this country:

You can put all your life together for free at this place they call a community centre: there are posters offering everything from pottery classes to anonymous meetings for alcoholics to cleaning jobs. Twenty dollars to clean someone’s house. So much more money than I have. Seems simple enough. I think it can be done. I’m feeling that now-elusive thing called hope that seems to duck in and out of me once every few weeks, teasing me with brief glimpses of something new and better.

Cold, a confusing language and a baffling new culture were what I was living, yet even then I was travelling to a brighter future. It helped that, right after gaining permanent resident status, I got a job working with refugees in newcomer centres. In their eyes I saw hope and resilience amid the challenge and pain of adapting to somewhere new. I also saw this hope and resilience — an insistence on belonging — in the stories I heard when I later worked for the United Nations Association in Canada and travelled around the country to teach young people about the Charter of Rights of Freedoms and learn about their concerns.

Immigration is an act of hope. It requires the ability to go somewhere better before something better comes along. Today, when I am asked, “Where is home?” I think it is where people are willing to offer the promise of change.

At Carleton, I’ve been able and allowed to carve out space for myself within the university community, on my own terms. Today, when I travel to distant worlds, it is not with the anguish I felt that evening as a child in that room in South Africa. It is with pleasure, because for the first time, I feel anchored. When you immigrate, you are always searching. Then you discover that feeling welcome and safe is home.

Kagiso Lesego Molope is a master’s student in Film Studies at Carleton and the author of four novels, including This Book Betrays My Brother, which won the 2019 Ottawa Book Award for English fiction.

Shifting Perspectives

A Photographer Turned PhD Student Looks at the World Through a New Lens

Words and pictures by Akintunde Akinleye

As told to Dan Rubinstein

It was his mother’s idea. Akintunde Akinleye didn’t plan to become a photographer.

Growing up in Lagos, Nigeria, when he wasn’t at school, he played football on the streets with friends. At age 11, to provide direction and discipline, his mother got him a camera and an apprenticeship at a nearby studio. Later, at university, he realized he could make money by selling pictures — an important consideration for a student from a middle-class family in a country going through a tumultuous period of “structural adjustment.”

That experience led to nearly 20 years of work as a photojournalist, during which he travelled throughout Nigeria and other African nations, documenting the continent’s conflicts, religious rituals and everyday moments, getting beat up and shot at, and winning the prestigious World Press Photo prize in 2007 for an image of a man rinsing soot from his face after a deadly pipeline explosion.

His images, including pictures documenting the human and environmental impact of oil production in the Niger Delta, have been published around the world and have been featured in several international exhibitions — “images that shock but also possess a formal beauty,” writes gallery director Oliver Enwonwu, with “an honesty of purpose clearly evident.” But despite that success, and a well-paying job with Reuters, Akinleye had always dreamed of becoming a teacher.

In January 2017, he took a leave of absence and enrolled in a film studies master’s program at Carleton, a trial run in a new country. Now he’s pursuing a PhD in anthropology at the university, studying the voodoo religion in Benin. Both his time in Canada and the act of trading his camera for a regimen of reading and writing have had a dramatic impact on how Akinleye sees the world.

Photography touches all aspects of life. Ethnicity. Politics. Class. Religion. Everything. It’s the same in Nigeria or Canada or any other country. My background as an undergraduate social studies student helped me begin to understand the planet and all the people around me. Later, when I roamed around Nigeria with my camera, I saw in real life some of the theories I had studied in the classroom.

Photography is a tool that you can use to capture societies as they change — to make a visual discourse about crime or poverty or infrastructure dilapidation. My mission as a photojournalist was to put history into perspective, so that distortion could be reduced to its barest minimum. My photography is a kind of agitation with aesthetics. Everything is woven around activism. There is a sort of agitation behind every single picture I try to create.

Journalism allows you to travel; life is never boring. But after so many years of doing it, I was starting to forget my initial goal to become a teacher. I wanted a new challenge. I needed a new landscape. Leaving home has given me a fresh perspective. Taking a break from photography has also been good for me. Now I want to look at things not journalistically but through a longer time scale, which is one of the things that drew me to anthropology. Anthropologists go somewhere and embody an environment; you embody that knowledge. Then you go back home and reflect and write about it. You’re not just observing people. You’re interacting with them.

I made some good pictures as a journalist, but my understanding wasn’t deep enough. Now I’ll be able to go back to some of the places where I went with my camera, like the annual voodoo festival in Benin, and look at things in a very different way. With anthropological critical theories in my head, the pictures I take won’t be any more “fantastic” than the work I did in the past, but they’re going to be more shaped, more focused, more purposeful. More “why” than “what” — that’s what I want to do.

It’s important to have a variety of experiences, both professional and cultural, whether you’re a journalist or a scholar, or for whatever else you do in your work and with your life. Learning about your world and your environment is something we need to do all the time. It means looking beyond the immediate.

In Lagos, there are 20 million people in a space about one-third the size of Ottawa. That’s like half of Canada. When you step outside, there’s always a picture waiting for you — a drama is going on, somebody is fighting or singing. The streets of Ottawa are different than the streets of Lagos. My first few months in Canada were a shock. It was the middle of January. Nobody really talked to me. But sometimes you need to see and feel these differences to remind yourself of the value of considering multiple perspectives.

People in Canada don’t see snow the same way I see snow, for example. For me, it’s art — it’s something that can tell stories about this place and this space, and how this country is utilized by the people who have occupied it and are living here. You can’t capture everything in one frame. But you can try to capture as much as possible.