By Catherine McKercher, Professor Emerita

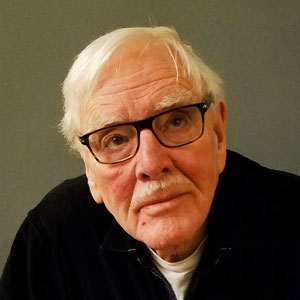

Carman Cumming was a mainstay of Canadian journalism education at Carleton for more than two decades, a mentor to students and colleagues alike, an admirable teacher, a passionate historian, and a talented and prolific writer.

Carman Cumming was a mainstay of Canadian journalism education at Carleton for more than two decades, a mentor to students and colleagues alike, an admirable teacher, a passionate historian, and a talented and prolific writer.

He would have blushed at this description, but that was Carman Cumming too.

Cumming died in March 2021, at the age of 88. Because of the pandemic, his friends, colleagues and former students did not have the chance to gather in his honour. They will get that chance on Saturday, May 28, at a reception at the School of Journalism and Communication’s Resource Centre, on the fourth floor of Richcraft Hall. The reception runs from 1 to 4 p.m.

Teaching was Cumming’s second career. His first was as a journalist for The Canadian Press (CP), the news-gathering co-operative funded by member newspapers across the country. After finishing the one-year Honours Bachelor of Journalism program at Carleton in 1955, he joined CP’s Toronto bureau as an editor. In 1960, he moved to its New York bureau and worked as an editor and UN correspondent. He did a Southam Fellowship at University of Toronto in 1965-66, then moved to the Ottawa bureau.

CP was a great training ground for his next career. Wire service work meant getting the story quickly and getting it right, though precision was more important than speed. In a newspaper world where big egos competed, CP served everyone equally. Superior news judgment and the ability to stay cool under pressure mattered.

Cumming brought those traits to Carleton as a sessional lecturer in 1969 and joined the faculty full-time in 1970.

Prof. Chris Dornan encountered him as an undergrad in the 1970s and became a colleague in the 1980s. “He was universally admired by the students as a knowledgeable, kind, patient and supportive journalism professor with a ready smile under that moustache,” he recalls.

Ed Greenspon took in-depth reporting with Cumming and wrote his Honours Research Project under his supervision. “Big influence on my career,” says Greenspon, president of the Public Policy Forum and a former editor in chief of The Globe and Mail. “From Carman, I learned about the how and the why of stories, which were always the hardest questions with the most interesting answers,” he recalls. “It stuck with me throughout my journalism career – how did that come about? Why did it happen? It took journalism into social and economic forces and the role of personality in shaping news.”

Prof. Barbara Freeman met Cumming in 1968, as a journalism student on a brief apprenticeship at CP Ottawa. “He gave me my first byline,” she recalls. Cumming sent her to to Parliament Hill to interview peace activist Claire Culhane, who was on a hunger strike to protest the Vietnam war. He went over her story with her, showing how to make it better, put her name on top and sent it out on the wire. “I was thrilled,” Freeman says. “It was a real prize for a beginner, especially a woman.” A dozen years later, she joined him on the faculty at Carleton. “We both wrote media history and he was always generous in sharing his insights, and sometimes his archival material, with me,” she says. “He was a trusted colleague and very good friend.”

Cumming’s accomplishments during his Carleton years are too numerous to tally. He rose from assistant to associate to full professor. He was co-author of a book-length study of news services for the Royal Commission on Newspapers, known as the Kent Commission. He was a commentator on media issues. He was acting director of the journalism school for a year, served on the university Senate, and took part in a teaching exchange with the University of Western Ontario. He helped develop the Master of Journalism program and taught its foundational reporting course, known then – and now – as boot camp. He taught in-depth reporting to hundreds of students.

He also helped new colleagues become better teachers. After I joined the faculty in the late 1980s, I was lucky enough to team-teach with him a couple of times. I learned so much. Prof. Roger Bird feels the same way. “He was someone I aspired to be and helped me over the hump when my duties came to actually teaching reporting,” he says. “He was a big brain and fortified my intellectual life.”

Through it all, his beloved Betty was his best critic and biggest fan. Carman Cumming and Betty Weir met as 20-year-old undergrads at University of Toronto in 1952. They married in 1955 and raised four children. Sean, Dan and Kim were born in Toronto; Chris in New Jersey. In his usual modest way, Cumming didn’t boast about them. But he was deeply proud of them all, and of his four grandchildren. The last time I dropped by his house to see him, his granddaughter Carmen was visiting. He was grinning from ear to ear.

In 1991, as he prepared to retire to spend more time with Betty, he came to my office with a stack of papers. His teaching notes, he said. He had typed them up and was thinking of depositing them in the School’s Resource Centre, but wasn’t sure they were any good. Would I read them? I did, and told him they were too good to sit in the resource centre. You have the basis of a reporting textbook here, I said, and you know we need one.

After some stammering and sputtering, he replied that he had half a textbook and asked whether I’d write the other half. The result was The Canadian Reporter: News Writing and Reporting, first published in 1994. It was the first-ever instructional text on how to be a reporter in this country, and it was adopted widely. A second edition came out in 1998, shortly after Betty’s death from cancer. A third, with the addition of co-author Prof. Allan Thompson – now head of the Journalism program – appeared in 2010.

While journalism deals with the present, Cumming’s scholarly interests leaned toward the historical. In 1992, he published Secret Craft: The Journalism of Edward Farrer, the brilliant and mysterious Toronto Mail editor who worked for the breakup of Canada and its annexation by the U.S. He followed that up in 1997 with Sketches from a Young Country: The Images of Grip Magazine, which looked at John W. Bengough’s influential cartoons as social history.

In 2004, he published Devil’s Game: The Civil War Intrigues of Charles A. Dunham, the story of a Civil War journalist, spy, forger, purveyor of fake news, and serial imposter who claimed the assassination of President Lincoln was the work of the Confederacy. While doing the research for this book, he came across another Civil War-era con artist with multiple aliases, Loreta Velàzquez. She claimed she dressed as a man and fought as a Confederate soldier, worked as a spy while dressed as a man or a woman, and was even a double agent for the U.S. secret service. Cumming worked on a book-length manuscript about her but another Civil War historian beat him to publication, so he set the project aside.

The appeal of these 19th century figures lay in disentangling fact from fiction. But also, he told me in an email exchange about this work, in showing “how people tend to believe what they want to believe.”

Cumming’s final years were marred by illness and the frailties of age. His partner Janet McDiarmid kept him smiling, and tried to keep him in line. Bridge games provided entertainment and social contact. Family visits were his great joy. And he never stopped writing. Among the material he left behind were manuscripts of a couple of novels. His family hopes to publish one of them, titled Jaime’s War. It’s the story of a young man, born and raised near Cumming’s childhood home, who goes off to fight in the First World War. Going back to Simcoe County sounds like a homecoming of sorts, and a fitting coda to the career of a man who was born to write.

Tuesday, May 10, 2022 in General, Journalism News, News

Share: Twitter, Facebook