By Hymie Anisman, Dept. of Neuroscience, Carleton University

By Hymie Anisman, Dept. of Neuroscience, Carleton University

Addictions, especially those involving drugs, continue to be a problem world-wide. Several neurobiological and psychosocial processes have been implicated in addiction, which have led to a variety of treatment strategies, although most haven’t been overwhelmingly successful. It’s hard to eliminate a well-entrenched habit, and it’s still more difficult to continue to stay clean. As Mark Twain is thought to have said, although others have attributed this quote to W.C. Fields (in the context of alcohol drinking), “It’s easy to quit smoking. I’ve done it hundreds of times”. Reminder cues and stressful experiences seem to activate systems that energize cravings that cause reinstatement of the addiction, particularly among those with impulsive characteristics. Anyone on a diet, or those with medical conditions, such as diabetes, that require them to watch what they eat, will know how easily they can be tempted, ‘just this once’.

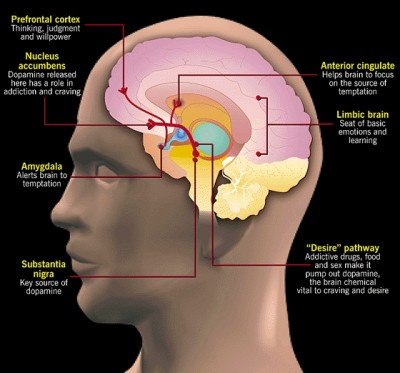

It isn’t coincidence that I’ve linked eating and drug addiction. There is the belief that cocaine and alcohol addictions and ‘eating addictions’ (although eating isn’t yet fully accepted as a genuine addiction) may involve some of the same neurobiological mechanisms. They each seem to involve activation of brain regions and neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine) associated with rewarding feelings as well as those that operate in making judgments and decisions. They also share another important characteristic. Specifically, there are ‘stop’ mechanisms involved in these addictions. In the case of eating, two hormones, ghrelin and leptin are responsible for the initiation and cessation of eating, respectively. There is likewise evidence that leptin might contribute to drug addictions (or reinstatement) and perhaps ghrelin plays some role in this regard as well. When an individual has consumed a certain amount of food, or used enough of a drug, changes of brain activity are provoked so that the message to stop eating or snorting a drug will kick-in, and for the moment, the intake ceases. Once the drug’s actions have worn off, and the euphoric effects are replaced by dysphoria, the individual again resorts to drugs either to ward off the ill feelings that otherwise emerge, or to regain the high they had experienced previously.

Image from http://sustainablenutritionlifestyle.com/all-addictions-share-the-same-principle-what-is-it/

But there’s more to addiction than just that. With repeated drug use the functioning of brain regions responsible for decision making and impulsivity are disturbed, so that those who are addicted engage in further use, ‘knowing that they can stop tomorrow’. As much as we would like to believe that each of us has free-will, in a sense, addicted individuals aren’t governed by the same forces. Simply put, their behavior doesn’t simply reflect abdication of responsibility, but as Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (in the US) suggested, drug addiction is an illness in which some cognitive abilities have been hijacked.

This brings me to another form of addiction. Gambling, like drug addictions, has been a considerable societal problem, but it receives much less attention. Perhaps it’s because gambling problems occur disproportionately often among poor people, although it also occurs among the wealthy, and has been a problem among college-aged individuals. Or perhaps, as problem gamblers don’t stagger or appear incoherent, and seem to function well, others might assume that a problem isn’t present. Yet, a gambling addiction can be as devastating as a drug addiction, possibly more so as it can be hidden from close others, at least until their money has evaporated and the house has been mortgaged.

Unlike the appetite for drugs and food, which can be sated, there doesn’t seem to be a ‘stop mechanism’ for gambling (other than the fatigue factor), and there’s no shortage of gambling venues to meet the need of those addicted. The ponies, cards, betting on football, baseball, basketball; gambling can be done at bars, and lottery tickets can be obtained at the gas station or the corner store, and for those who prefer privacy, the internet seems to be a comfortable companion. Of course, for the social gambler, what’s more enticing than the casino?

In the old days, gambling might have been controlled by the mob, and as their casinos grew, private investors entered the scene as well, and considerable research went into finding ways to enhance profits. This amounted to increasing their customer base, and having customers bet for a longer duration and/or greater amounts. This tax deductible “market research” indicated that the lighting, oxygen circulation, alcohol, the nature of the game (e.g., slots vs cards or craps), presence of hostesses, as well as restaurants, all improved their bottom line. They learned ways of exciting customers by making (tricking) them feel as if they almost won (e.g., getting two cherries and one lemon, but having the lemon appear right next to a third cherry on a slot turn), even though the simple fact is that they lost (again). In lotto games and in slots, winners might win a free ticket or a number of free spins, which might seem like ‘a win’, but the free tickets or the free spins, typically don’t result in actual wins. Ridiculously, players might win 20 cents on a $1 spin (meaning that they actually lost 80 cents), but with the sounds and lights that accompany this ‘win’, the loss actually feels like a win. Even the term ‘gambling’ was changed to ‘gaming’, which seems to have less stigma attached to it. Of course, players still call it gambling, but for management that doesn’t want players to think they’re taking high risks, the term ‘gaming’ is preferred. Parcheesi is a game, so is chess. Bingo was a game, until it turned into gambling, but let’s be realistic, there’s no way that slots and craps are just a game.

Casinos shared some of their loot (which annually exceeded $37 billion a few years ago) by paying taxes, and governments were fairly happy with this profit-sharing arrangement. However, witnessing the profits that could be made, some governments decided they wanted in on the action, and chose to cut out the middleman. They began to run their own lotteries that offered both instant and delayed gratification (or disappointment), built and operated fancy casinos, and in case you couldn’t get to the casino they placed the big money maker (slots, which ‘earn’ about $100,000 per machine) in bars and at racetrack. Having learned from the years of earlier research, the government operated gambling ventures, involving the very same routines to maximize profits. With unlimited funds, they also advertised their product on every type of media outlet. This has continued for several decades, expanding considerably over time.

Casinos shared some of their loot (which annually exceeded $37 billion a few years ago) by paying taxes, and governments were fairly happy with this profit-sharing arrangement. However, witnessing the profits that could be made, some governments decided they wanted in on the action, and chose to cut out the middleman. They began to run their own lotteries that offered both instant and delayed gratification (or disappointment), built and operated fancy casinos, and in case you couldn’t get to the casino they placed the big money maker (slots, which ‘earn’ about $100,000 per machine) in bars and at racetrack. Having learned from the years of earlier research, the government operated gambling ventures, involving the very same routines to maximize profits. With unlimited funds, they also advertised their product on every type of media outlet. This has continued for several decades, expanding considerably over time.

Everything seemed to be moving along just fine, but a problem seemed to creep up that could have some negative repercussions. The government-run casinos might be associated with increased gambling addiction and consequently an increase of depressive illness and suicide. Indeed, the likelihood of gambling addictions was elevated in the few kilometers surrounding new casinos. To be sure, this is just a correlation, and the two events could have been independent. It’s akin to saying that drownings occur where there are oceans, lakes, rivers or swimming pools; these don’t cause drownings, but they wouldn’t have occurred if these waters weren’t accessible.

How would it look for the government to be complicit in provoking addiction? So they came up with the clever notion of funding research to prevent or curb addiction. Why not target a small portion to gambling addiction research? It’s unlikely that governments were simply paying out ‘guilt’ money. Instead, this was a well thought out public relations effort (look, we’re doing good things in addition to offering the possibility of jobs for the community, and bringing in badly needed tourist money!). The gaming industry (including manufacturers of gambling equipment) soon followed suit, and they too offered funds for research. It was argued that many ‘problem gamblers’ (this is a choice term, as it makes it seem that the individual is the problem, not the system set up to create gambling addiction) would have fallen into addiction irrespective of whether or not governments owned casinos, and so research funded using casino revenues might be a public service. Yup, and I just fell off a turnip truck!

In next week’s blog, I will take a look at the role researchers have had in fighting against, or in the interests of, the gambling industry.

Hymie Anisman has recently authored two book providing an evidence-based approach to understanding the role of stress on human health, and identifying characteristics and behaviours that render people more vulnerable or resilient. Both are available at Amazon.ca