By Maria Pranschke, M.Sc., Department of Neuroscience

Can having a pet improve your health? Ask any pet owner with a close relationship to their dog or cat and you’ll probably get a resounding “Yes!” Many researchers will also tell you that the scientific findings regarding the association between having pets and health look pretty positive. Links have been found between owning pets and multiple aspects of physical and mental well-being, including lower risk of death (Kramer, Mehmood, & Suen, 2019), better heart health (Mubanga et al., 2017), better sleep and exercise habits (Headey, Na, & Zheng, 2008), and less loneliness (Stanley, Conwell, Bowen, & Van Orden, 2013).

Can having a pet improve your health? Ask any pet owner with a close relationship to their dog or cat and you’ll probably get a resounding “Yes!” Many researchers will also tell you that the scientific findings regarding the association between having pets and health look pretty positive. Links have been found between owning pets and multiple aspects of physical and mental well-being, including lower risk of death (Kramer, Mehmood, & Suen, 2019), better heart health (Mubanga et al., 2017), better sleep and exercise habits (Headey, Na, & Zheng, 2008), and less loneliness (Stanley, Conwell, Bowen, & Van Orden, 2013).

While the scientific literature on pets and health is promising, a closer look reveals that the story isn’t always consistent. Some studies have been unable to detect links between owning an pet and key health outcomes (Wright, Kritz-Silverstein, Morton, Wingard, & Barrett-Connor, 2007), and some researchers have even found that owning a pet can predict negative health outcomes (Koivusilta & Ojanlatva, 2006). Some of the inconsistencies can probably be traced back to variations in the way studies were conducted, but it might also be that different individuals and social groups experience pet ownership differently. In other words, there could be key social, psychological, and even biological factors that influence how much (or little) benefit people get out of sharing their lives with animals. The goal of our research was to move beyond just asking whether or not pets are good for our health, to focus instead on characteristics that might alter this relationship. For example, is a pet’s presence enough, or does the strength of the bond matter? Does having a supportive social network affect the way you feel about your pet? Do stressful life circumstances (like illness, homelessness, or poverty) change our relationships with animals and how important they are for our health?

At the same time as we try to better understand the psychosocial factors that contribute to the benefits of pet ownership, a growing body of research has converged on oxytocin (a hormone known for its role in stress reduction, bonding, and many other social behaviours) as a possible major biological player in our interactions with animals. Prior studies have shown that oxytocin levels in our body change in the presence of a friendly animal, particularly when it’s an animal we’ve bonded with (Handlin et al., 2011). Oxytocin appears to impact our brain and body’s stress response, potentially connecting positive social behaviours (like turning to a friend for help) to the reduction of distress (Heinrichs, Baumgartner, Kirschbaum, & Ehlert, 2003). Differences in genes that are responsible for oxytocin functioning appear to impact the way we relate to others on a social level, including how we pursue and respond to social support (Chen et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2010). If bonds with cats and dogs are similar to bonds with people, could genetic variation in our oxytocin system similarly affect human-animal relationships?

At the same time as we try to better understand the psychosocial factors that contribute to the benefits of pet ownership, a growing body of research has converged on oxytocin (a hormone known for its role in stress reduction, bonding, and many other social behaviours) as a possible major biological player in our interactions with animals. Prior studies have shown that oxytocin levels in our body change in the presence of a friendly animal, particularly when it’s an animal we’ve bonded with (Handlin et al., 2011). Oxytocin appears to impact our brain and body’s stress response, potentially connecting positive social behaviours (like turning to a friend for help) to the reduction of distress (Heinrichs, Baumgartner, Kirschbaum, & Ehlert, 2003). Differences in genes that are responsible for oxytocin functioning appear to impact the way we relate to others on a social level, including how we pursue and respond to social support (Chen et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2010). If bonds with cats and dogs are similar to bonds with people, could genetic variation in our oxytocin system similarly affect human-animal relationships?

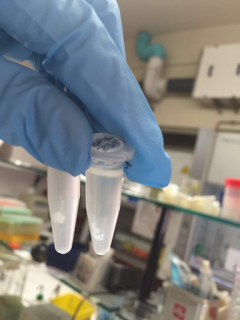

To explore these questions, we conducted a series of studies that combined survey measures (assessing emotional attachment to pets and facets of human health & well-being) with genetic analysis. By isolating DNA from saliva samples, we were able to look at small variations known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (or SNPs) in oxytocin-related genes and test for links between people’s genetics and their survey responses.

The research began in the fall of 2017 when we rented booth space at the Ottawa Pet Expo, a weekend event for pet enthusiasts. While there, we gathered survey responses and saliva samples from 100+ pet owners—mostly people with dogs and cats but a few with other types of animals. In a second study, we set up our booth at public locations around Ottawa and repeated this procedure; this time we also encouraged participation from non-pet owners as a comparison group. Finally, our third study took place at events organized by Community Veterinary Outreach, an organization that provides free veterinary care for low-income, marginally housed community members in Ottawa. Gathering data from these different populations allowed us to look at how the role of pets might differ based on personal circumstances.

The research began in the fall of 2017 when we rented booth space at the Ottawa Pet Expo, a weekend event for pet enthusiasts. While there, we gathered survey responses and saliva samples from 100+ pet owners—mostly people with dogs and cats but a few with other types of animals. In a second study, we set up our booth at public locations around Ottawa and repeated this procedure; this time we also encouraged participation from non-pet owners as a comparison group. Finally, our third study took place at events organized by Community Veterinary Outreach, an organization that provides free veterinary care for low-income, marginally housed community members in Ottawa. Gathering data from these different populations allowed us to look at how the role of pets might differ based on personal circumstances.

As soon as we began analyzing the data, the results challenged our assumptions. We had predicted that strong feelings of attachment towards a pet would be linked to improved mental well-being, but in fact an opposite pattern emerged – in all three groups, participants who were more strongly bonded to their animals were also more likely to report experiencing poorer well-being, including more symptoms of depression, loneliness, and lower feelings of social connection. Strong attachment to pets was also associated with being more likely to have a physical illness.

What could these results mean? While it’s possible that strong emotional ties with an animal directly negatively impact human well-being (perhaps because caring for a pet might strain time and financial resources), we believe that it’s more likely that when people are highly emotionally stressed (depressed, lonely, or socially isolated), they may be more likely to turn to their pets for comfort. Some evidence for this possibility exists in the form of research showing that many pet owners view their animals as unique and important sources of support, especially when they are strongly attached to their pet (Meehan, Massavelli, & Pachana, 2017). If people are turning to their pets as a way of coping with things like stress and loneliness, this could explain why animal relationships are often so important to people who are isolated or socially marginalized, like older adults and individuals who are homeless. In fact, in our own research, we found that participants who were living with poverty and housing insecurity were especially likely to say that they were highly attached to their pets.

We also found that a SNP of the oxytocin receptor gene was linked to owning a pet. Results from a large twin study released earlier this year suggested that a tendency towards having animals (in this case, dogs) might be influenced by a person’s genetic make-up (Fall, Kuja-Halkola, Dobney, Westgarth, & Magnusson, 2019), which makes this a particularly interesting finding. However, the relatively small number of participants in our own study means that this finding should be taken with a grain of salt; repeating this research with a larger group would be one way to check if the association is meaningful or not.

We also found that a SNP of the oxytocin receptor gene was linked to owning a pet. Results from a large twin study released earlier this year suggested that a tendency towards having animals (in this case, dogs) might be influenced by a person’s genetic make-up (Fall, Kuja-Halkola, Dobney, Westgarth, & Magnusson, 2019), which makes this a particularly interesting finding. However, the relatively small number of participants in our own study means that this finding should be taken with a grain of salt; repeating this research with a larger group would be one way to check if the association is meaningful or not.

As with any study, it’s important to remember that lots of different factors might have affected the results, including when and where we gathered data, who was motivated to take part in the research, and how we chose to measure things like attachment and well-being. While our findings were unexpected, the takeaway from this research is not that we should ignore pets and their role in human health—these are important phenomena that need to be studied and explored, especially when pets seem to be so important to so many people. But as with research into any interesting human behaviour, the relationships between pet ownership, emotional bonds with animals, and health & well-being are bound to be complex. Learning more about these links will be challenging, but worthwhile.

References:

References:

Chen, F. S., Kumsta, R., Dawans, B. v., Monakhov, M., Ebstein, R. P., & Heinrichs, M. (2011). Common oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphism and social support interact to reduce stress in humans. PNAS USA, 108(50), 19937-19942.

Fall, T., Kuja-Halkola, R., Dobney, K., Westgarth, C., & Magnusson, P. (2019). Evidence of largegenetic influences on dog ownership in the Swedish twin registry has implications forunderstanding domestication and health associations. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 7554-7.

Handlin, L., Hydbring-Sandberg, E., Nilsson, A., Ejdebäck, M., Jansson, A., & Uvnäs-Moberg, K. (2011). Short-term interaction between dogs and their owners: Effects on oxytocin, cortisol, insulin and heart rate—An exploratory study. Anthrozoös, 24(3), 301-315.

Headey, B., Na, F., & Zheng, R. (2008). Pet dogs benefit owners’ health: A ‘natural experiment’ in China. Social Indicators Research, 87(3), 481-493.

Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., and Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 1389–1398.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., Sasaki, J. Y., Xu, J., Chu, T. Q., Ryu, C., . . . Taylor, S. E. (2010). Culture, distress, and oxytocin receptor polymorphism (OXTR) interact to influence emotional support seeking. PNAS USA, 107(36), 15717-15721.

Koivusilta, L. K., & Ojanlatva, A. (2006). To have or not to have a pet for better health? PloS One, 1(1), e109.

Kramer, C. K., Mehmood, S., & Suen, R. S. (2019). Dog ownership and survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

Mubanga, M., Byberg, L., Nowak, C., Egenvall, A., Magnusson, P. K., Ingelsson, E., . . . Institutionen för kirurgiska vetenskaper. (2017). Dog ownership and the risk of cardiovascular disease and death – a nationwide cohort study. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1-9.

Stanley, I. H., Conwell, Y., Bowen, C., & Van Orden, K. A. (2014). Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging & Mental Health, 18(3), 394-399.

Wright, J. D., Kritz-Silverstein, D., Morton, D. J., Wingard, D. L., & Barrett-Connor, E. (2007). Pet ownership and blood pressure in old age. Epidemiology, 18(5), 613-618.