“Summary of Disasters”: Introducing Disaster Lab Research on the Canadian Red Cross

What is a disaster?

The answer, I always thought, was subjective. A disaster was, well, you know, a disaster. No additional thought required.

However, when Laura Madokoro approached me about working on The Disaster Lab, I had never considered the multiple meanings of the term. My primary research involves discourse analysis and an examination of the competing ways that language is used to support policy decisions. Embarrassingly, however, I still get ensnared in the trap of thinking of certain terms as static.

The meaning of disaster – before the Disaster Lab – seemed relatively straightforward to me. In a series of posts here, I will explore the fundamental question of what has constituted a disaster and introduce some of the early findings from my research. Spoiler: I have found that the very concept of disaster has evolved considerably over the course of the 20th century. My research will also critically analyze how events are defined (as disaster, emergency, or other) and how these definitions have a measurable impact on what aid is provided and by whom.

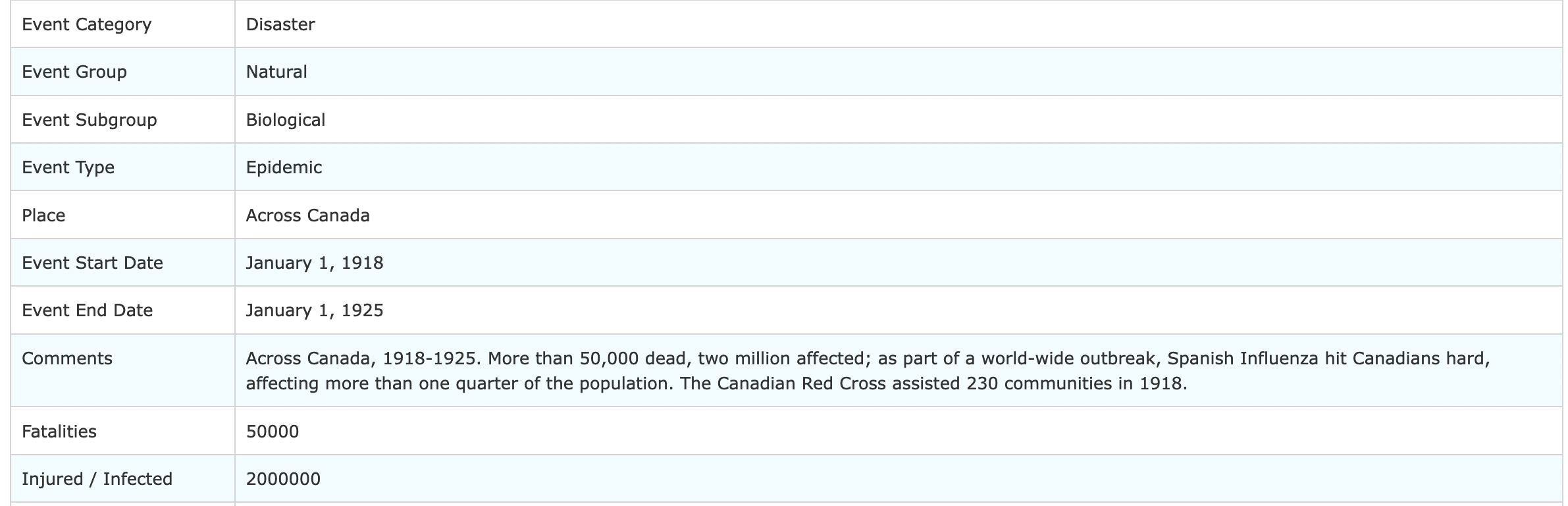

My first task in tracking this evolution was identifying disasters in Canadian Red Cross (CRC) Annual Reports between 1943-2020. In the early years, each province submitted a report from their Disaster Services Committee which included an in-exhaustive list of disaster responses. As the society professionalized over the last eighty years, the reporting style changed and, increasingly, only large-scale disasters were highlighted in the annual reports. The language used to describe events that had once been termed disaster also evolved; however, the annual reports largely provided clear (though still in-exhaustive) lists of CRC domestic responses. Once I had a spreadsheet with over 200 disasters (almost entirely from post-1945), I then compared the CRC definition(s) of disaster to the current definition used by Public Safety Canada in their Canadian Disaster Database (CDD).

As of December 2021, the Canadian Disaster Database defines a disaster as an event that meets any of the following criteria:

- 10+ people killed

- 100+ people affected/injured/infected/evacuated/made homeless

- An appeal for national/international assistance

- Historical significance

- Significant damage/interruption of normal processes such that the community affected cannot recover on its own

One of the more striking questions from this criteria on how CRC conceptualizes disaster is how it compares to Public Safety Canada’s parameters? Exactly what does Public Safety Canada mean by “affected” and has the notion of who is affected changed as our response to disaster has changed

For example, in 1962 the Disaster Services Committee of the Nova Scotia Red Cross reported they had assisted three adults following a shipwreck off the coast. No further information was given about the nature of the assistance and – by the current national definition – this event would not constitute a disaster. At the time, however, the provincial Disaster Services Committee considered it the second biggest disaster in the province (though still characterized it as a ‘minor disaster’).

In contrast, when 17 people were killed when a helicopter crashed in the North Atlantic off the coast of Newfoundland in 2009, the Canadian Red Cross reported that it had assisted over 300 family members and friends who were awaiting news. The CRC support centre operated 24 hours a day and provided emotional and material support to the community. In 2009, CRC reporting had changed and this marine accident was included in a list of disasters, but itself was characterized as a “tragedy.”

As these two events highlight, a change in how civil society responds to disasters has a measurable impact on the number of people they consider to be in need of assistance. Not that the family and friends of those directly involved in the 1962 shipwreck did not require emotional and material support, only that – at the time – the CRC appears to have provided assistance mainly to direct victims and/or rescue crews. One of the biggest changes to disaster response in Canada between 1962 and 2009 appears to have been how civil society (Canadian Red Cross) and all three levels of government shared responsibilities. As Canada faces an increasing number of large-scale climatic events, understanding the history of disaster response and the often overlapping and competing mandates of organizations and governments may provide a roadmap for understanding what an effective future could be.

These posts will dive deeper into the history of the Canadian Red Cross’ disaster response, explore some of the challenges of treating disaster as a monolithic idea, and introduce some of the questions and ideas that we at the Disaster Lab hope to tackle in the coming years!

– PhD Candidate Helen Kennedy