Summer (and Wildfire Season) Are Not Yet Over

As September ushers in feelings of a new school year, the once casual “how was your summer?” exchange has taken on a sombre tone. Informally speaking, nearly every conversation I’ve had this past week with friends from across the country has come with a tone of hesitation.

“I didn’t really feel like I had a summer” was a repeated refrain.

“The smoke is so thick the trees think it’s winter,” came another sobering observation from Northern Alberta.

Relaxing in the cool shade of tree canopies and swimming in a crisp body of water come to mind of “summer” activities, but between the wildfires affecting air quality in May/June and the searing heat of the hottest July in human record, my own summertime was hardly memorable between monitoring air health quality indices and upgrading my sunscreen game.

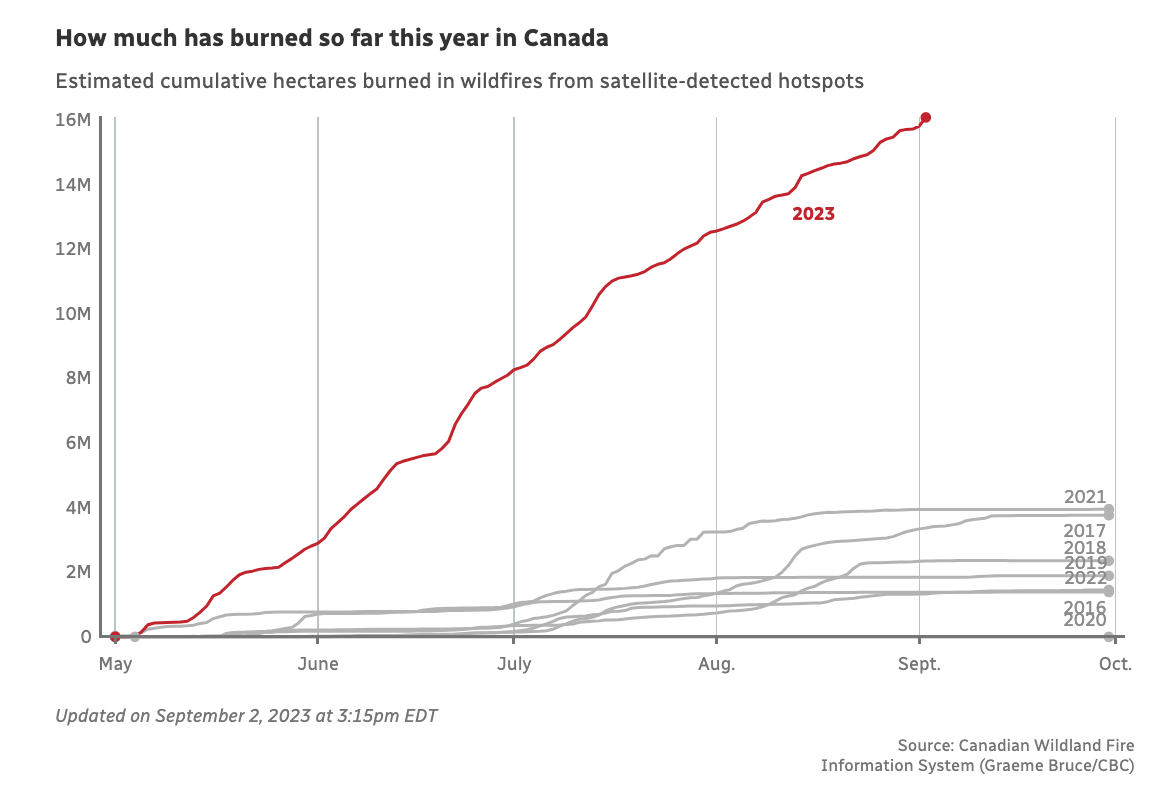

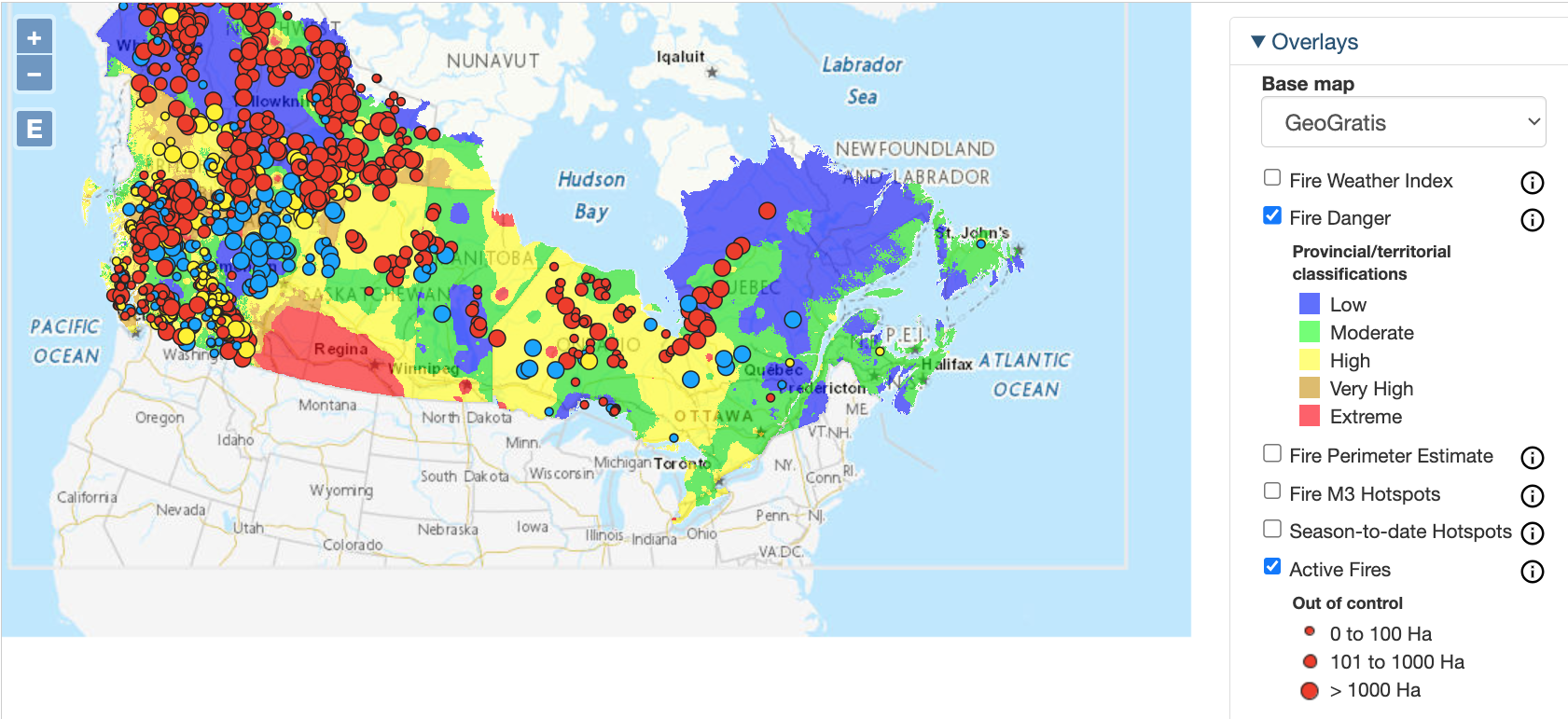

As I write over a Labour Day weekend while sitting under an extended heat warning advisory covering most of Southern and Eastern Ontario into Quebec, hundreds of wildfires are still raging across the country in what has been the worst wildfire season in Canada with projections that these wildfires will continue into the Fall. Beyond the immediate devastation to wildlife and air quality (and yes, a lacklustre summer), we should be gravely concerned for the long term impacts of burning tens of millions of hectares of forest in one year, or possibly in successive years.

Researchers at Disaster Lab have tracked the historic records for how the federal government has perceived, defined, and addressed disasters in our past to better understand how we may prepare for the present and future scenarios. As historians living through one unprecedented moment after another, it is important to understand the past for context and patterns.

Looking at the parameters, how we define “disasters” have been human-centric and shaped by how humanitarian organizations like Red Cross have categorized events as “major,” “minor,” “personal” or “large scale.” The boundaries between these categories are based on quantifiable metrics such as number of people affected which in turn defines funds allocated. However, the intensity and scale of climate disasters such as floods and wildfires would do well to be be understood beyond human impact alone. Because the fact of the matter is: the natural environment will survive without humans, but humans are wholly dependent on nature for our essential survival.

Beyond enjoying (and extracting) from nature to meet our short term needs, humans have taken more than our fair share and abused our responsibilities. When I hear people talk about stewardship of land, I understand this is based on Indigenous laws, praxis and knowledge that humans are “earth-bound” and intrinsically rely on maintaining a reciprocal relationship with nature. At the end of the day, human beings are part of the environment and not above or outside of it. I interpret reciprocity as coming down to this: if humans don’t take care of nature, nature cannot take care of us.

Blackfoot scholar Dr. Leroy Little Bear has pointed out the “very narrow gap of ideal conditions” for humans to survive on earth, which I thought a lot about this summer. We really are physically frail creatures that cannot endure conditions either too hot or too cold; we cannot hold our breath for that long; we cannot fly; and we cannot even move that fast on land on our own accord. Humans have invented our way to the supposed top, but no matter where we are on the proverbial food chain, we still need clean water to drink and clean air to breathe.

Living in a settler capitalist society means discourses and policies still think we can carbon tax our way out of climate change, but if that were true, who would be paying for the 160m tonnes of carbon and 600m tonnes of carbon dioxide released this summer? The delulu we maintain thinking green capitalism will save us is certainly being tested more regularly, but we could lose a lot more than a summer season if political leaders keep treating our stark reality as aberrations.

-Amy Fung