A Hurricane is Not Just a Hurricane

The impact of Hurricane Hazel can be approached from a spatial historical perspective. Spatial history focuses on the relationship between humans and place over time. These relationships can be many things; physical, cultural, and economic, and the focus on this relationship gives space the capacity to act on the people that interact with it. In the context of Hurricane Hazel, the extreme flooding, damage to homes, and the legislating of certain areas as no longer safe to live had wide-ranging impacts on individuals’ and communities’ relationships to their spatial environments, depending on their country’s emergency responses. By charting the development of these relationships through time, we can gain insight into how the legacies of natural disasters shape the interplay between people and place nationally, internationally, and transnationally.

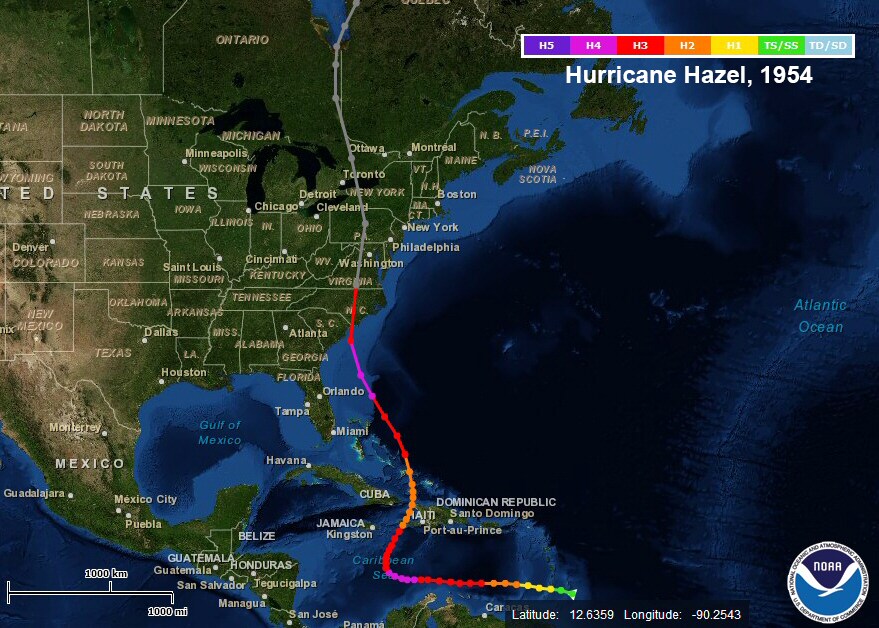

In early October 1954, Hurricane Hazel was born in the Caribbean sea. On October 05, Hazel raged close to Grenada, and then the next day slipped between the islands of Grenada and Carriacou. Suddenly, two days later on October 07, the storm changed direction westward heading towards Haiti’s western tip, and when it hit near Baie-de-Henne with winds of 200 kph, total devastation followed. An estimated 400 to 1000 people were killed (the largest death toll compared to the other countries hit by Hurricane Hazel,) infrastructure such as homes, roads, electrical grids and water systems were damaged and many coffee and cacao plantations were destroyed causing long term impacts on Haiti’s agricultural industry.

By October 15, Hazel touched down in North Carolina causing a storm surge of nearly 15 feet and 240 kph. 19 residents passed away and 15,000 homes were destroyed. Hazel continued blazing a path through the United States, causing similar damage in the southeastern to northeastern seaboard states of Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York, costing the United States $281 million in 1954 USD ($5 billion in 2024 CAD).

On October 15 Hazel hit Toronto at 11 pm EST, and in the next 48 hours she ripped the city apart. Winds blew in around 110 kph and 285 millimetres of rain fell. Toronto flooded dramatically due to the Humber River drainage basin being deforested in 1946, so the water flowed freely, and the area’s floodplains were saturated already due to heavy rain in the days before. The flooding washed away roads, houses, bridges, and led to an estimated loss of 81 Ontario residents, many of whom drowned. In addition, Hazel left 4,000 people homeless and caused $100 million in 1954 CAD of damage (approximately $1 billion in 2024 CAD.)

The tragic effects of Hurricane Hazel has had a lasting impact on the communities and environments that fell in its path. When viewed historically, Hurricane Hazel offers an important opportunity to understand how emergency preparedness and response have changed over time from the local to the global level. This post asks: can Hurricane Hazel, and national disasters more broadly, offer unique insight into societal norms and values of their time?

Given Hazel’s devastating impact on multiple countries, the borderless nature of natural disasters provides an opportunity to approach the past from international and transnational perspectives. When viewed internationally, differences in emergency response can give insight into the impact of wealth disparity, colonial legacies, and international relations. Further research into the case study of Hurricane Hazel could provide valuable insight into the varying national responses to the hurricane and investigate how disaster relief, economic damage, and displacement are approached across national borders. A transnational approach to studying Hazel could raise important questions about which communities and diasporas are impacted and how international aid workers contribute to the understanding of disasters at home and abroad. Through approaching the historical record with these questions in mind, a transnational approach to studying Hurricane Hazel may offer a more expansive view of the socio-political context of disasters, and provide insight into whether these relations born out of distress have in some way shaped the present-day communities who rebuilt after Hazel.

With the continued rise of extreme weather, we believe the interconnection between human activity and natural disasters will be increasingly relevant to researching the impact of climate change. By approaching these topics historically and transnationally, we hope to develop a better understanding that a hurricane is more than just a natural disaster, but also shape human activities, responses, and relationships across space and time.

– Holly Sutton-Long and Katie Carson