By Amanda Pappin, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Carleton University.

By Amanda Pappin, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Carleton University.

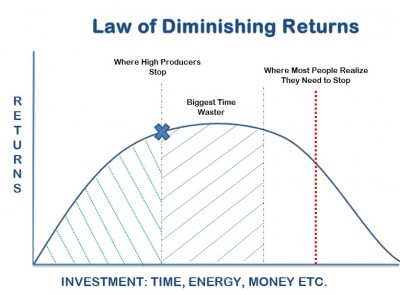

We have all experienced the law of diminishing returns. It shows up in various scientific disciplines and in our everyday lives. Weight loss is one example that often comes to mind. If you cut your food intake by a fixed amount, initially weight comes off quickly. But with each pound that disappears from the scale, it seems that you have to work even harder to lose the next. Your diet hasn’t changed, and other factors like exercise are the same as before, but that scale just isn’t budging. Frustrating, right?

Well, the law of diminishing returns also applies to various topics in economics. At least that’s what we thought was the case for air pollution economics.

Air pollution poses a significant challenge to environmental managers because what is emitted from the tailpipe of a car, or the stack of an industrial facility, can undergo profound changes in the atmosphere before affecting the air we breathe. Some of the major pollutants that pose risks to our health are not emitted directly, but rather formed in the atmosphere through complex physical and chemical processes. These include pollutants that we often hear about, such as ozone or small airborne particles (particulate matter or PM). Epidemiologists have shown that both pollutants affect human health and increase our risks of illness and even death.

Air pollution poses a significant challenge to environmental managers because what is emitted from the tailpipe of a car, or the stack of an industrial facility, can undergo profound changes in the atmosphere before affecting the air we breathe. Some of the major pollutants that pose risks to our health are not emitted directly, but rather formed in the atmosphere through complex physical and chemical processes. These include pollutants that we often hear about, such as ozone or small airborne particles (particulate matter or PM). Epidemiologists have shown that both pollutants affect human health and increase our risks of illness and even death.

For a long time, economists who study air pollution have believed that the societal payback of reducing pollutant emissions is a battle against diminishing returns. Cleaning up polluted air brings large benefits to our health and the environment. Cleaning up less polluted air by the same amount yields much smaller benefits. Economists have argued that the environment has a natural ability to cleanse itself of pollution – an ability that works best when pollution is at low levels. As the air becomes more polluted, the environment becomes overwhelmed and cannot remove added pollution as effectively.

My colleagues and I at Carleton University have tested the validity of the theory of diminishing returns as it relates to air pollution. For the first time, we attached numbers to the benefits of reducing emissions to see how they change as we strive to emit less pollution. Our work, just published in the Journal Environmental Science & Technology as a Policy Analysis article, sheds new light on the topic.

We used a numerical air quality model, infused with epidemiological and economic data, to estimate the benefits of reducing emissions on a per-ton basis. We defined “benefits” as the number of deaths avoided in the population because of reduced ozone, which we converted to dollar values. We focused on the benefits of reducing emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx), which are major players in formation of ground-level ozone. NOx is emitted from motor vehicles and industrial facilities when air comes into contact with high temperatures in fuel combustion.

We used a numerical air quality model, infused with epidemiological and economic data, to estimate the benefits of reducing emissions on a per-ton basis. We defined “benefits” as the number of deaths avoided in the population because of reduced ozone, which we converted to dollar values. We focused on the benefits of reducing emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx), which are major players in formation of ground-level ozone. NOx is emitted from motor vehicles and industrial facilities when air comes into contact with high temperatures in fuel combustion.

Our objective was to test whether the per-ton benefits of reducing NOx emissions decline over time, as environmental economists have suggested. And we found just the opposite. We showed that instead, benefits increase substantially as we continue to emit less. In other words, each additional ton of NOx emission reduction becomes more beneficial than the previous ton. While looking for diminishing returns, we instead found compounding benefits!

Los Angeles smog

We found that, on average in the U.S., reducing NOx from vehicles yields benefits of $13,000 per ton of NOx. On an average per-vehicle basis, the price tag of NOx emissions can be as high as $870 per year. This number varies depending on where the vehicle is driven, with benefits tending to be larger around populous urban areas than in the countryside. What about diminishing returns? On average, the benefits of reducing NOx emissions would almost double if we reduce emissions across the country by 60%. Further, if we reached a level of zero man-made emissions, this benefit would quadruple, on average, yielding benefits of $51,000 per ton. The 4-fold average increase in benefits means that adjusting our way of life not only benefits society now, but will also bring benefits for the future. Every dollar that we spend to clean up our air makes the next dollar invested even more valuable.

So why do our findings disagree with the conventional view of diminishing returns in economics? It comes down to a lack of data, resources, and models to assess the adequacy of the theory in question. Only recently have engineers and atmospheric scientists used their comprehensive numerical models for economic applications. And those who have done so had not fully explored the assumptions used in this theory.

To an atmospheric chemist or air pollution scientist, the idea of diminishing returns in air pollution is counterintuitive for pollutants like ozone. Ozone is formed through photochemical reactions in the atmosphere, and its formation depends on how much NOx and other pollutants are emitted. In polluted air, each emitted NOx molecule has to compete with many others to form ozone. As the air becomes cleaner, and NOx less abundant, these molecules are in higher demand. It is for this reason that our results come as little surprise to researchers in atmospheric chemistry and air pollution. But for economists, our findings are surprising, and frankly, a bit bizarre.

A challenge facing environmental managers is that while cleaning the air entails indisputable health and environmental benefits, doing so also costs money. Not only does it cost money, the cost increases as we emit less and less, and at some point, surpasses the expected societal benefits. Economists argue that it is to society’s benefit for environmental policies to progress to the point of equilibrium where incremental benefits equal costs, and no further. The question of whether benefits diminish or compound is one of great importance to finding this target level of emission reduction. Under the long-held view of diminishing returns, there is less incentive to keep reducing emissions, and the point of equilibrium is closer to our current habits. Our findings offer a new perspective. Compounding benefits provide further incentive to reduce emissions, and to keep reducing, towards an equilibrium point further down the policy trajectory.

So while you opt more and more to commute by bike or by foot to achieve that next pound of weight loss, know that society will increasingly benefit as you do.

So while you opt more and more to commute by bike or by foot to achieve that next pound of weight loss, know that society will increasingly benefit as you do.

This blog is based on:

Pappin, A.J., Mesbah, S.M., Hakami, A., & Schott, S. (July 24, 2015, web). Diminishing Returns or Compounding Benefits of Air Pollution Control? The Case of NOx and Ozone. Environmental Science & Technology.

Stream image courtesy of Evgeni Dinev at FreeDigitalPhotos.net