An eider nest is surveyed near Cape Dorset by a team of hunters and researchers from Environment Canada and Carleton University studying the effects of disease and predation on nesting birds.

By Jennifer Provencher, Department of Biology, Carleton University

A striking step forward in environmental protection policy was the creation of the Minamata Convention signed by 128 countries in 2013. As of April 2015, ten countries had ratified the convention. The Convention aims to limit the release of mercury into the environment. Although mercury is naturally found in the environment, it is also released by a number of industrial processes. Methyl mercury is a known neurotoxin that affects animal development and reproduction. The most extreme example of mercury poisoning for humans is from Minamata, Japan (where the convention’s name comes from). The people of Minamata were exposed to mercury through industrial wastewater from a nearby chemical factory in the mid-1950s. The mercury released into the sea bioaccumulated in the shellfish and fish in the area, which were main food staples for the local residents. Feeding on this seafood resulted in acute mercury poisoning, causing a severe neurological disorder among humans now known as Minamata disease.

Although the Minamata Convention is potentially a huge win for environmental protection, there is much work to be done. First, there is the task of ratification by each participating country, which must alter their national legislations to align with the Minamata Convention. Once all the new legislation is in place, countries must then have programs and enforcement in place to ensure that stakeholders are compliant with the policies on release and disposal of mercury. And there is still the task of designing and implementing monitoring programs to evaluate whether the steps put into place are in fact having the desired effect of reducing mercury in the environment and in wildlife. One stage for this environmental play is the Canadian Arctic.

In the Canadian Arctic, mercury in many habitats and species has been studied, with samples from water and plankton through intermediates in the food chain up to polar bears and humans. Some of the most extensive data sets on mercury are available for animals in the Canadian Arctic, which allows researchers to study how mercury is changing in the environment over time. Seabirds have been particularly useful as study species for researchers who are interested in the effects of mercury, and the overall trends of mercury in northern ecosystems. Environment Canada researchers and its National Wildlife Specimen Bank, located on Carleton University’s campus, have played an important supporting role in this research. Several marine birds have shown that mercury levels in the Canadian Arctic have increased since the 1970s, and continue to rise in some areas (Riget et al.; Science of the Total Environment doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.05.002). A recent study looking at specimens dating back to the 1800s show that some bird species that are high in the Arctic food chain are experiencing a 45 fold increase in mercury over the last century (Bond et al. 2015; The Royal Society 10.1098/rspb.2015.0032). This increase contrasts with decreases seen in persistent organic pollutants in seabird tissues following policy measures over a much shorter time frame: from the 1970s to present (Braune et al. 2010; Interdisciplinary Studies in Environmental Chemistry).

Hunters return to home with eider ducks after a day of spring hunting. Samples are taken from the birds to study parasites and contaminants, and then the Hunter and Trapper Association distributes the meat among the community.

Studying and measuring mercury in marine birds each year socio-cultural perspectives. Marine birds are an integral part of both traditional culture and modern practices in northern Canada. Their eggs are collected for food during the breeding season and duck and goose down is a valuable insulating material that continues to be collected today by many for both personal use and commercial sales. Marine birds are also hunted for their meat, and their skins are used for household items such as slippers, bowls and jackets. Currently, there are many concerns in the north including rising food costs, sustainability, healthy food choices, and the need to better integrate traditional knowledge with science for ensuring viability of harvested populations. It is hard to argue with the value of marine birds as traditional foods: they are after all free range, organic, sustainable, locally grown, locally harvested, healthy to eat and grounded in cultural practices. Marine birds continue to have very low levels of mercury making birds like geese and ducks (along with caribou and other country foods) great sources of healthy, local nutrition. It is perhaps not happenstance that they are also used as ‘sample sentinels’ for studies on possible changes in pollutant levels of importance to human health.

An eider skin basket made by the Fur Production and Design class at the Nunavut Arctic College in Iqaluit as part of their annual wildlife workshop.

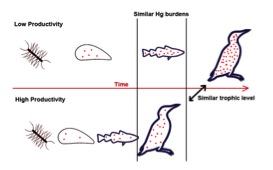

There are other reasons why we should be ‘keeping an eye’ on mercury in Arctic marine birds. The story of mercury cycling in the environment is much more complex than can be captured by a single international agreement. Mercury levels in northern Canada are not influenced by North American emissions, but have the potential to be greatly influenced by those from Asia. Even with the Minamata Convention in place, emissions from some regions in Asia are not predicted to slow for decades, and even when they do, it may take decades to cease increasing levels in Arctic ecosystems (Provencher et al. 2014; Environmental Reviews dx.doi.org/10.1139/er-2013-0072). One only has to go to smog-filled streets of Beijing to see how distant the Canadian Arctic is. Additionally, warming trends in the north that are causing the melting of glaciers and permafrost may be releasing large quantities of mercury into the environment. The low productivity of the Arctic may also make top-level predators susceptible to bioaccumulating more mercury than their counterparts in ecosystems with higher productivity . Thus, arctic marine birds in Canada may be particularly at risk from increasing Hg levels associated with long-term Hg deposition patterns and changing climatic conditions.

Schematic of how a system with low productivity with slow growing biota may lead to exacerbated mercury burdens in top predatorsas compared with more productive, faster growing systems

Canada still needs to ratify the Minamata Convention and research is needed to continue to monitor mercury in marine birds and northern ecosystems. Through these studies, we can help determine if any policies put in place are leading to the desired outcomes (a reduction in environmental mercury). These studies also will help us understand both the acute and sub-lethal effects of mercury on organisms. This research can continue to contribute to other conversations around human health and sustainability in the Arctic, and be used to engage northern students in science, building capacity and helping people make informed decisions (Provencher et al. 2013; Arctic). So although legislators have succeeded with an international agreement on mercury, it is the continued work on mercury and marine birds that has the potential to help inform and evaluate policies and also to shape education, health and culture.

Based on Provencher, J.F., Mallory, M.L., Braune, B.M., Forbes, M.R., Gilchrist, H.G., 2014. Mercury and marine birds in Arctic Canada: effects, current trends and why we should be paying closer attention. Environmental Reviews 22, 244-255.