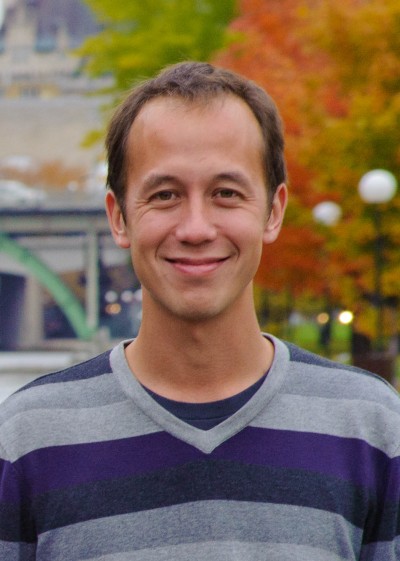

Alex Wong, Department of Biology

Alex Wong, Department of Biology

By Ariel Root

Bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and can be found in virtually every corner across the planet. Some bacteria perform important roles in the environmental ecosystem, whereas others help us digest food or absorb nutrients. Still other bacteria can cause life-threatening diseases. “They’re really cool. They do different things, and do lots of things that we don’t even think or know about. It’s fascinating how they can generate so much diversity,” says Carleton University’s Alex Wong. And then there’s the interesting issue of antibiotic resistance. A growing challenge has emerged as more bacteria are becoming resistant…a challenge that is well-worth investigating.

Alex Wong is an Assistant Professor of Biology at Carleton University, focusing on the genetic causes and consequences of biological adaptation. He is interested both in characterizing the direct genetic targets of natural selection, and in studying the indirect effects of selection throughout the genome. “I am particularly interested in investigating the consequences of genetic interactions (epistasis) for rates and patterns of molecular evolution, and in understanding the potentially non-adaptive consequences of natural selection.” So basically, how do some bacteria become resistant to antibiotics, and what could this all mean for health and illness.

Wong’s academic career started as a mix of the hard and social sciences. Following his BA in philosophy and biology, Wong pursued a Masters of Philosophy at Carleton, establishing his ability to synthesize information, think critically, and write cohesively. Wong then studied the rapidly evolving reproductive proteins in fruit flies during his doctoral work at Cornell University, questioning the specific genetic changes that lead to character trait changes in an organism. His introduction to Psuedomonas wasn’t until postdoctoral work at the University of Ottawa, where he developed a keen interest in evolutionary observations in the lab.

Wong’s academic career started as a mix of the hard and social sciences. Following his BA in philosophy and biology, Wong pursued a Masters of Philosophy at Carleton, establishing his ability to synthesize information, think critically, and write cohesively. Wong then studied the rapidly evolving reproductive proteins in fruit flies during his doctoral work at Cornell University, questioning the specific genetic changes that lead to character trait changes in an organism. His introduction to Psuedomonas wasn’t until postdoctoral work at the University of Ottawa, where he developed a keen interest in evolutionary observations in the lab.

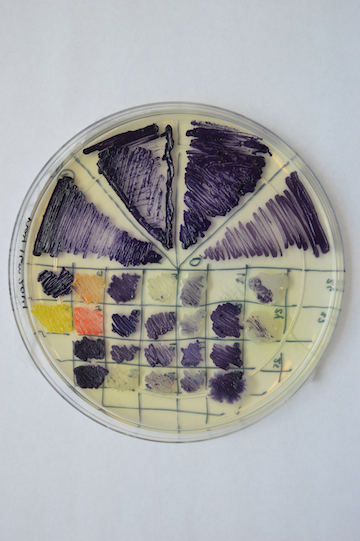

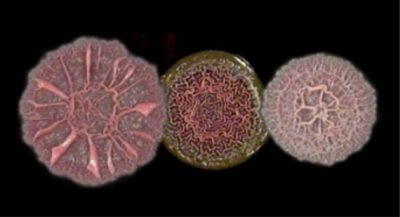

While choosing a bacteria to study can be difficult, Wong describes one of his main research projects is an experimental evolutionary study of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa – a pathogen associated with inflammation and sepsis, and colonizes in organs such as the urinary tract, kidneys, or lungs. “Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a bacterium found in wet environments such as soils, bathtubs, a kitchen sink… and it’s mostly harmless.” However, the bacteria can be especially of concern for immunocompromised individuals—most notably, those with cystic fibrosis. “Because these individuals’ lungs are full of fluid, it provides the ideal breeding ground for the bacteria, … and some cells can persist despite antibiotics.” Introduction to P. aeruginosa as a teenager can result in cells that remain into adulthood, when the uniquely nutritional environment in the lungs of these individuals enables the bacteria to create colonies that can flourish. Unforeseen diminishing lung strength in these individuals is beginning to be associated with a long-ago introduction to P. aeruginosa.

Wong has explored some of the evolutionary resistance in bacterium using a variety of tools, such as the computational analysis of population genetics and comparative genomic data, experimental evolution, and molecular genetics. It’s all about “new ways to find vulnerabilities that are unique to bacteria… [some] are resistant to one or more antibiotics, while others are not vulnerable at all.”

Wong has explored some of the evolutionary resistance in bacterium using a variety of tools, such as the computational analysis of population genetics and comparative genomic data, experimental evolution, and molecular genetics. It’s all about “new ways to find vulnerabilities that are unique to bacteria… [some] are resistant to one or more antibiotics, while others are not vulnerable at all.”

Using the theories and practices of evolutionary biology in an applied setting related to individual care basis, or policy is what keeps Wong excited. However, in order to tackle antibiotic resistance, he acknowledges that health needs be thought of in the broader framework that considers social sciences, policy, and hard sciences. “Policy on how we use [antibiotics], to public education on antibiotics in agriculture, down to the genetics of antibiotics… the goals of the [CHAIM] Centre fit exactly with how we need to think about resistance – multi-dimensionally.”

The challenge in these investigations, Wong says, is that “things rarely work out the way we think they’re going to. It’s part of the fun, and part of the frustration,” he laughs. When thinking about resistance, Wong reiterates how important external partnerships have been with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, University of Ottawa, and internationally.

Some of Wong’s challenges have also become his strengths. He describes times that his “favourite hypothesis is also the false hypothesis. But then,” he says, “it’s fun to figure out what is actually going on.” In fact, working with students in the lab has been particularly rewarding for Wong. Getting students into the lab, analyzing data, and fostering interest and inspiration, Wong and his students continue the journey to finding new ways to identify the unique vulnerabilities to some of the antibacterial resistances.

Some of Wong’s challenges have also become his strengths. He describes times that his “favourite hypothesis is also the false hypothesis. But then,” he says, “it’s fun to figure out what is actually going on.” In fact, working with students in the lab has been particularly rewarding for Wong. Getting students into the lab, analyzing data, and fostering interest and inspiration, Wong and his students continue the journey to finding new ways to identify the unique vulnerabilities to some of the antibacterial resistances.

For Dr. Wong’s contact information, go here.