By Ariel Root, Department of Health Sciences

By Ariel Root, Department of Health Sciences

“The land is everything. It’s family, it’s kin, it’s friends. It’s a part of you.” — Ashlee Cunsolo Willox, TedX Cape Breton, Nov 25 2014.

Health geographer, community researcher, and environmental advocate, Ashlee Cunsolo Willox visited Carleton University on February 5th to help convey the strong connections the Inuit have to the land, and the direct and indirect impacts of climate change.

In 2008, Cunsolo Willox was invited by the Rigolet community government to conduct narrative research regarding the impacts of climate change on health, where she identified, with the community, that mental health was a primary concern of community residents. Since then, she has worked with all five Inuit communities in Nunatsiavut, Labrador on a variety of community-led and community-identified research initiatives, including cultural reclamation and intergenerational knowledge transmission, suicide reduction and prevention, and land-based education and healing programs. “I’ve always said, that I work at a university, but [I work] for the communities.”

The Canadian Arctic has the fastest changing annual temperatures, and “this is a big deal… because of the sea ice, and it’s impacted ability to form,” says Cunsolo Willox. In 2012, Cunsolo Willox and a team of Inuit researchers from the communities launched the Inuit Mental Health and Adaptation to Climate Change project, to examine the relationships between people, places, cultures, environments, and mental health in the region.

The Canadian Arctic has the fastest changing annual temperatures, and “this is a big deal… because of the sea ice, and it’s impacted ability to form,” says Cunsolo Willox. In 2012, Cunsolo Willox and a team of Inuit researchers from the communities launched the Inuit Mental Health and Adaptation to Climate Change project, to examine the relationships between people, places, cultures, environments, and mental health in the region.

There are approximately 2600 people living in Nunatsiavut, spread between five communities: Nain, Hopedale, Postville, Makkovik, and Rigolet. Each community is located on the coast, and winter freezing is critical for transportation, obtaining supplies, and following traditional hunting patterns and sea ice is incredibly important for each community.

Nunatsiavut Inuit communities rely on, and thrive from, their natural environment; however, condition changes within the recent years has impacted their ability to access the land. Changes in annual temperatures have impacted animal migration patterns, weather behaviours, and sea ice integrity. Some Arctic animals are seeking cooler temperatures and migrating further north, while new animals, such as moose, are migrating into the Nunatsiavut communities. Changes in weather patterns, including increasing fog levels, wind speeds, and precipitation, are especially of concern as they impact sea ice formation and quality; sea ice that has traditionally supported travel, has a much shorter annual season.

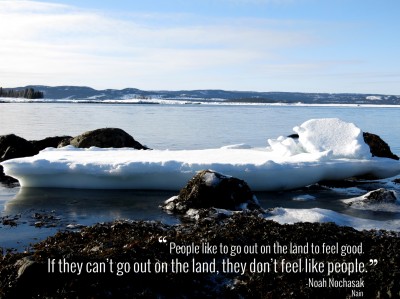

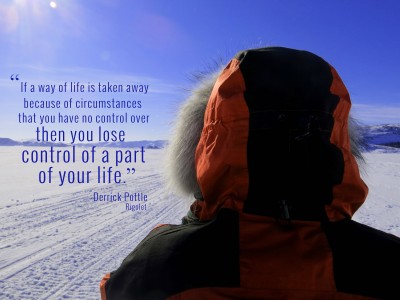

Each change has an impact all aspects of Inuit lives and livelihoods and, as Cunsolo Willox and the research team discovered, the changes also have profoundly affected mental health, eliciting a major emotional responses across the region. Cunsolo Willox and the team identified from interviews with 120 people that “the biggest [effects] were those in mental health. The psychological impact of the changing climate was [initially] a big surprise.” Cunsolo Willox relayed one story about learning from an Elder in Rigolet: “She was telling me about…how the ice had changed. But what she wanted me to know most… was to understand the strong connections that Inuit have to the land. It’s everything… if you can’t get out on that land, it’s like you’ve lost a part of yourself. The land provides healing. It provides solace. It provides peace. So what happens if you can’t access that land anymore?”

Each change has an impact all aspects of Inuit lives and livelihoods and, as Cunsolo Willox and the research team discovered, the changes also have profoundly affected mental health, eliciting a major emotional responses across the region. Cunsolo Willox and the team identified from interviews with 120 people that “the biggest [effects] were those in mental health. The psychological impact of the changing climate was [initially] a big surprise.” Cunsolo Willox relayed one story about learning from an Elder in Rigolet: “She was telling me about…how the ice had changed. But what she wanted me to know most… was to understand the strong connections that Inuit have to the land. It’s everything… if you can’t get out on that land, it’s like you’ve lost a part of yourself. The land provides healing. It provides solace. It provides peace. So what happens if you can’t access that land anymore?”

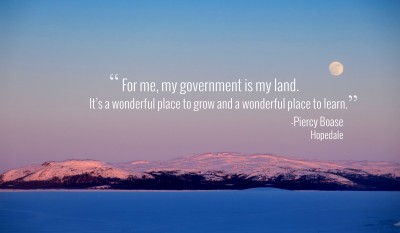

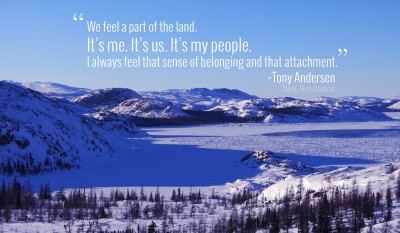

These findings inspired production of the documentary film, “Lament for the Land.” The film used interviews, scenery, and action shots throughout Nunatsiavut to conceptualize the deep connection between the Labrador Inuit and their homelands through their voices and lived experiences.

Interviews for “Lament for the Land” revealed the importance of being able to access and connect with the land as a coping mechanism. Denied access to the land because of changing weather patterns meant loss of access to a place that supported reflection, and provided comfort. The inability to access the land due to insufficient sea ice formation directly and indirectly affects mental, and overall, health.

“Inuit are people of the sea ice. If there’s no more sea ice, how can we be people of the sea ice?”

Cunsolo Willox identified that these rapidly changing conditions impact the already over-burdened health systems, the path to health sovereignty, and the overall Inuit culture. Climate changes have yet added another colonial stressor that is out of their control. “It’s important to understand the past,” suggests Cunsolo Willox. Residents in Labrador were the first to have contact with European settlers more than 300 years ago. There is a long history of interaction, which includes residential schools, and relocation, and has resulted in intergenerational trauma. “And yet, they have such a rich culture. There is so much beauty in the region.”

Both Cunsolo Willox’s “heart and mind are in Labrador because [she’s] been there so long, [she has] relationships, and [has] seen so much evolution.” When asked what continues to inspire her, Cunsolo Willox simply responds “everything; it’s the beauty of the land; it’s the list of endless questions; it’s the discovery and sense of pride; the shared ownership of research; the communities.” While respect and willingness within the communities have eliminated most challenges, there are still barriers and hurdles at the provincial and federal governance level, especially as they relate to the funding of such interdisciplinary work. Despite these challenges, Cunsolo Willox “cannot imagine life without this work. I never expected it, and now, I cannot imagine working anywhere else. It’s changed me as an individual and my world-views; my interconnectedness. What I’ve learned from the people I’ve worked with, to listen to their wisdom, [it] has been a huge privilege.”

Photos by A. Cunsolo Willox