By Veronica Zuccala, Department of Neuroscience

The spread of COVID-19 has created stress worldwide and continues to disrupt our day-to-day lives, making it very difficult to sustain healthy habits. Even as we seek to find a new normal, health care professionals and public figures continue to encourage us to “stay home” and “take time for yourself”. For those of us who find ourselves with some extra time on our hands, this can be a good opportunity to reflect on our mental and physical health. Ask yourself these questions:

- Do you exercise daily?

- Do you give your body the proper nutrients it needs? (and no mom, that doesn’t include evening Häagen-Dazs)

- Do you average 7-9 hours of sleep every night?

- Are you able to effectively manage your day to day stress?

Our body operates as a cohesive and interconnected system. If we do not manage ALL of these contributors to our health (exercise, nutrition, sleep, stress management), then the system (our mental and physical health) may fail.

Why is mindfulness an important place to start?

Over the past 20 years there has been a vast body of research linking emotional intelligence to positive physical and mental health outcomes. Emotional intelligence is defined as the ability to monitor feelings and emotions (your own and the emotions of others), to provide objective judgement, and to use this information as a guide for your thinking and actions (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Some experts believe that emotional intelligence is the key to success for personal relationships, professional relationships, and the relationship you have with yourself (Goleman, 2006; Zinn, 2003). It has also been suggested that emotional intelligence is not an innate skill, and that we can use mindfulness practices, such as meditation, to train these competencies in order to improve our quality of life (Goleman, 2006).

An eye-opening study led by Richard Davidson and Jon Kabat-Zinn (2003) examined the benefits of practicing meditation in a business setting. After eight weeks of using meditation techniques, employees reported significantly lower levels of anxiety and stress. Additionally, when electrical activity was measured in the brains of participants, the meditation group showed a significant increase in left-side anterior brain activation (i.e., parts of the brain associated with positive emotion). They also developed more antibodies to a flu vaccine than employees who did not meditate, suggesting that in addition to the positive psychological effects, those who practiced mindfulness developed stronger immune responses. In my opinion, the most exciting takeaway from this research is that it may be possible to train our minds so that our bodies become stronger!

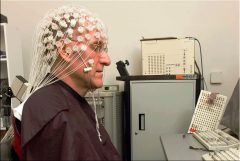

A Buddhist monk meditating with EEG for neuroscience research

Another study demonstrated that practiced Buddhist meditators are able to voluntarily regulate their brain activity to generate high-amplitude gamma brain waves, which have been linked to more effective memory, learning and perception (Lutz et al., 2004). Electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings were used to compare the brain activity of eight Buddhists who had been practicing meditation for 15-40 years to a group of ten healthy students who had been practicing meditation for one week prior to the study. The skilful meditators were able to sustain high-amplitude gamma brain waves and phase-synchrony (a measure linked to higher-level mental processes) during meditation and also displayed higher baseline gamma-wave activity than the student group, suggesting that mental training may induce both short- and long-term changes in the brain (Lutz et al., 2004).

Other studies have demonstrated the value of mindfulness-based stress reduction practices for medical students and health care professionals, including doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers and physiotherapists (Shapiro et al., 1998; Jain et al., 2007; Shapiro et al., 2005). By comparing individuals who engaged in mindfulness meditation to those who did not, these studies variously showed that consistent mindfulness practice led to decreased psychological distress, lower stress levels, and less burnout. Another study assessing the self-care practices and well-being of mental health professionals found that a state of mindfulness was key in linking self-care to well-being (Richards et al., 2010). Given that current work conditions for our health care professionals are extremely stressful due to COVID-19, the results of these studies could inform efforts to help workers stay healthy both mentally and physically as they courageously work through these difficult times.

Together these studies demonstrate the positive effects of mindfulness training after only a few weeks of practice. If mindfulness practices can provide benefits to corporate employees, Buddhists, students, and health care workers alike, then they can certainly be helpful to all of us. Let’s learn about these practices!

The simple practice of mindfulness

Hopefully at this point you’ve started to evaluate how you can do better with self-care, regardless of where you think you currently stand on the “healthy” scale. Now I’m going to explain two easy practices that you can try.

Breathing techniques – Bringing attention to breath is a simple and effective form of meditation (Tan, 2018). Try these simple steps:

- Position yourself for meditation: begin by sitting comfortably. Sit in a position that enables you to be both relaxed and alert at the same time, whatever that means to you.

- Take 3 deep breaths: take three slow deep breaths to inject both energy and relaxation into our practice.

- Bring attention to what you are doing: breathe naturally and bring very gentle attention to your breath. You can bring attention to the nostrils, the abdomen, or the entire body of breath, whatever that means to you. Become aware of the in breath, the out breath and the space in between. If at any time you feel distracted by a sensation, thought or sound, just acknowledge it, experience it and gently let it go, then bring attention very gently back to your breath.

Practice this breathing technique for one minute. If you are able to hold you attention for longer, then you may lengthen the practice. This is about quality, not quantity, so if you feel you can’t sit still and focus for more than a few minutes, then try this exercise for 1 minute and build on it from there. And, because I like science, here is some evidence that shows what simple breathing practices can do for you. Valentine and Sweet (1999) compared long-term meditators, novice meditators (who were trained to focus on breath) and non-meditating controls on the Wilkins’ counting test which measures the ability to sustain attention. As expected, the long-term meditators displayed superior performance in sustained attention, but the more interesting finding was the difference between novice meditators and the control group. With short-term training designed to focus on breathing, the novice meditators greatly outperformed the controls in sustaining attention. This suggests that although long term meditation provides the best benefits, even simple short-term practices can give you an edge.

Journaling – This exercise only requires 3 minutes of your time (set a timer)! You will give yourself a prompt and spend 3 minutes writing whatever comes to mind. Try not to think about it too much, just let the words flow onto the paper. If you run out of things to write, just write, “I have run out of things to write” until the 3 minutes is up. You can create your own prompt or use one of the following: What I am feeling now is, I am aware that, What motivates me is, I am inspired by, Today my focus is, I wish, Others are, Love is, I am grateful for…

Once again, because I like science, Spera, Buhrfeind and Pennebaker (1994) conducted a study where laid-off professionals wrote about their feelings for twenty minutes every day for five consecutive days. These individuals found new jobs at a much faster rate than the non-writing control group. Another study found that an 8-week gratitude journaling intervention for elderly patients experiencing heart failure lead to positive physiological outcomes such as reduced inflammation (Redwine et al., 2016). Although this study used a 20-minute journaling period, it’s important to tailor these practices to you and how long you can sustain your attention. Whether that means 3 minutes, 10 minutes, or 20 minutes is up to you. That is the whole idea behind these practices: becoming more in tune with what works for you so that you can take the appropriate steps to improve your health.

When working towards a healthier lifestyle, it’s important to have as many tools in your (figurative) toolkit as possible so that you can handle any situation life throws at you, and evidence shows that these techniques can work! But remember, knowing how to do something does not mean that you have mastered it. New skills must be practiced, and when you are training new habits, consistency is key. There’s no magic number for how many workouts to complete, how many cheat meals you’re allowed, or how many weeks you need to practice mediation for it to work. Practice, practice, practice!

To conclude, consider mindfulness as a new skill you can develop during this time of distancing and isolation. One minute of paying attention to your own needs might just turn a bad day into a good one. I wish everyone well during these challenging times. Stay healthy and stay you.

References

Davidson, R. J., Kabat-Zinn, J., Schumacher, J., Rosenkranz, M., Muller, D., Santorelli, S. F., … & Sheridan, J. F. (2003). Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic medicine, 65(4), 564-570.

Goleman, D. (2006). Emotional intelligence. Bantam.

Jain, S., Shapiro, S. L., Swanick, S., Roesch, S. C., Mills, P. J., Bell, I., & Schwartz, G. E. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of behavioral medicine, 33(1), 11-21.

Kabat‐Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 10(2), 144-156.

Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Rawlings, N. B., Ricard, M., & Davidson, R. J. (2004). Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences, 101(46), 16369-16373.

Redwine, L., Henry, B. L., Pung, M. A., Wilson, K., Chinh, K., Knight, B., … & Mills, P. J. (2016). A pilot randomized study of a gratitude journaling intervention on HRV and inflammatory biomarkers in Stage B heart failure patients. Psychosomatic medicine, 78(6), 667.

Richards, K., Campenni, C., & Muse-Burke, J. (2010). Self-care and well-being in mental health professionals: The mediating effects of self-awareness and mindfulness. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 32(3), 247-264.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, cognition and personality, 9(3), 185-211.

Shapiro, S. L., Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. International journal of stress management, 12(2), 164.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of behavioral medicine, 21(6), 581-599.

Spera, S. P., Buhrfeind, E. D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1994). Expressive writing and coping with job loss. Academy of management journal, 37(3), 722-733.

Tan, C. M. (2018). Search inside yourself. Bentang Pustaka.

Valentine, E. R., & Sweet, P. L. (1999). Meditation and attention: A comparison of the effects of concentrative and mindfulness meditation on sustained attention. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2(1), 59-70.