Ryan, Phil. 1995. The fall and rise of the market in Sandinista Nicaragua. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

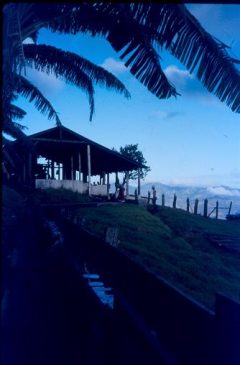

Coffee co-op, 1986, probably near Esquipulas

A warm Sunday afternoon, January 1987. I am doing guard duty with Don Andrés, on a hill overlooking La Sorpresa, a state farm with some 140 hectares of good coffee land, about 60 kilometres north-east from the departmental capital of Jinotega. Perhaps to avenge its former owner, an officer of Somoza’s National Guard, the farm has been destroyed twice by the contras, in 1983 and 1985. Outside the door of the hut in which we sleep there is a simple wooden cross, in memory of sixteen coffee pickers murdered during the 1985 attack.

Today, though, the farm is quiet below us: people are reading, chatting, or cleaning their rifles. Everyone enjoys the week’s one half-day of rest, renewing their energies for the next set of twelve-hour days of coffee picking. In the distance the sun reflects off the sheer white rocks of Peñas Blancas, an area that in previous years was the scene of constant fighting.

Don Andrés elbows me: “There are people climbing that hill over there.” I strain my eyes at the hill, about a kilometre away, but see nothing. “Don’t you see, that fellow in the white shirt just there”. Eventually I make out a white speck moving up the hill.

Don Andrés is from this area, and has lived most of his life here. He now works as a gardener in Managua, but promises to return to the mountains as soon as the war is over. “Life can be beautiful here, when you don’t have to carry a rifle around everywhere, carry all these bullets, watch every step for mines.” And he knows these mountains: whenever our squad has to come down a mountain at four in the morning after a night of guard duty, I place myself right behind him and keep my eyes fixed on his knapsack, which is the only thing I can pick out in the dark. He never falls, and always manages to pick out the obstacles and warn me. No one in my squad knows how old Don Andrés is. He seems old, so we call him “Don” out of respect, but I suspect that this is only because he has lost most of his teeth.

Farm workers, 1985, south-west of Pueblo Nuevo

The situation here says much about the subtle ways the United States-organized contra war undermined the Nicaraguan economy. We have come from Managua to pick coffee because many of those who have traditionally done so have gone to war. We are not terribly good at the task: most of us are confirmed urbanites, bureaucrats in various government ministries, and our energies are sapped by the hours of nocturnal guard duty. Even if we were master coffee pickers, yields would be down, because, like the traditional coffee pickers, many of those who used to tend the coffee plants between harvests have gone to war.

This is a first simple truth about Nicaragua: the United States proxy war ground this country into the dust. There were spectacular acts of aggression, such as the attack on Corinto, the country’s main port, in late 1983, or the mining of that same port in 1984. But the more common pattern was one of “low intensity” mayhem: attacks on state farms and cooperatives, the murder of rural teachers, health care workers, agricultural extension specialists.

But there is a second truth about Nicaragua, one which those of us who supported the Sandinista revolution find more uncomfortable. Listen again to Don Andrés: “Look, here you have to take sides. But I tell you, things were better before. The peasant today is really screwed. Before you could work hard, go into a store, and say ‘Give me sugar.’ And you could buy as much as you wanted. ‘Give me batteries,’ and there was none of this crap about ‘We can only sell you two.’ A man would work hard, and he could sell his crop to anyone he wanted, buy from anyone he wanted, buy whatever he wanted. He didn’t have to travel miles to buy and sell.”

One can judge this lament however one wishes. One might feel that the freedoms whose loss he mourns were empty, that the freedom to buy “as much as you wanted” was the freedom to buy only as much as your miserable earnings allowed, that freedom of commerce was but the freedom to be ripped off coming and going by merchants who sold the fruits of the peasant’s labour five times dearer in Managua and gave him goods in return at ten times their real value.

This may well be true, but it is also, at the moment, irrelevant. Don Andrés feels what he feels, his experience has made him sceptical of socialist critiques of market freedom, and thousands of Nicaraguan peasants feel more or less the same. This is a second simple truth about Nicaragua: the Sandinista project made its contribution to the country’s crisis. It alienated a good many people – peasants and others – and it fostered severe economic difficulties.

Our third simple truth is that the first two truths are intimately related. For reasons I cannot quite understand, Don Andrés is here beside me, guarding the state farm. But many people who think much like him are in the mountains around us, carrying guns for the other side. If the farm is attacked, it will be attacked not by the “mercenaries” and “beasts” depicted by the Sandinista media, nor by the “freedom fighters” hailed by Reagan, but by peasants. “Cannon fodder”? Definitely. “Manipulated”? To an extreme. But not without their motives. If the United States provided the material resources for the contras, Sandinista policy helped generate a social base from which the contras could draw human resources. In addition, much government policy helped intensify the economic impact of the war.

Morning militia practice, 1985, south-west of Pueblo Nuevo: ‘Drove in this morning. In the heart of contra country. This place was destroyed a couple of years ago.

After the electoral defeat of the Sandinista National Liberation Front [FSLN] in February 1990, much debate among supporters of the Nicaraguan revolution would revolve around the relative importance of these three simple truths. Thus, Argentine observer Carlos Vilas commented that “We have to recognize that the revolutionary process got stuck in its own internal tensions and ambiguities long before the Sandinistas were defeated at the polls. By then, the rank and file were already weakened and demobilized.” He added that “The free and secret ballot became for many voters a means for repudiating specific aspects of the Sandinista administration that were personally irritating: the over-bearing bureaucrat; the illicit enrichment of a Sandinista neighbour; the boss’ sexual harassment; the lack of textbooks in the schools while novels, declarations, and speeches by the leaders abounded; dilapidated public buses alongside the manager’s air-conditioned car.”

Vilas’ remarks were angrily dismissed by two United States supporters of the Sandinistas: “the FSLN and the Nicaraguan revolution were the victims in an unequal battle with the United States. Vilas’ search for ‘What Went Wrong?’ essentially boils down to a ‘blame the victim’ argument. Precisely ‘what went wrong’ is that Nicaragua was forced into the boxing ring with an opponent many times its material and military strength.”

The debate might be seen as a reflection upon one of Marx’s oft-quoted phrases: were the Sandinistas brought low by “circumstances not of their choosing,” or by the way they sought to “make history”? What must be added to Marx’s dictum is that some of the circumstances not of the Sandinistas’ choosing were nevertheless of their making. One of Camus’ characters says that “after forty, a person is responsible for his face.” Similarly, after a few years in power decision-makers are responsible for at least part of the history that weighs like a nightmare upon them…

Note: I didn’t have my camera with me at La Sorpresa. I took these pictures elsewhere over the years.