By: Leslie Rao & Maria Urso

What does it take to be considered “essential” in a pandemic? How is the term “essential” used by small businesses—particularly those deemed as not essential by provincial health orders over the past two years—as they navigated and coped with Covid-19 closures?

The Government of Canada defines essential work as participating in critical infrastructure, which facilitates the “health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government.” The term, however, became a buzzword attached to conversations that addressed which businesses were allowed to stay open during lockdowns versus those that were forced to close during the Covid-19 pandemic. This developed as a measure of importance for the non-essential small businesses who were forced to close while malls, big-box and liquor stores remained open.

We examined the hashtag “WeAreEssential” to understand how businesses reacted to pandemic policy and how the pandemic triggered a re-examination of essential work as an opposition to official government policy. We collected posts on Instagram that used #WeAreEssential between April 1 to June 30, 2021. This timeframe documents the pandemic’s third wave in Canada, as well as the aftermath when businesses waited for permission to reopen. It offered the opportunity to explore how the discourse in the hashtag adapted to the different stages of re-opening plans. Our Instagram dataset comprises 1788 posts.

Two Dissent Expressions in Two Industries

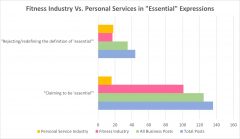

“Claiming to be ‘essential’” and “rejecting/redefining the meaning of ‘essential’” are two expressions of dissent in the #WeAreEssential dataset. In particular, the former is the most common compared to all other observed expressions. Among 136 posts from users that argue they are essential by either adopting or rephrasing the term “we are essential,” 125 are businesses—even though they do not provide essential services as recognized by the government and public health authorities. Of the closely related expression, 44 posts involve “rejecting or redefining ‘essential,’” in which 35 are generated by businesses. In contrast to those which claim their businesses are essential, these posts reject the official definition of essential or raise alternative interpretation of essential jobs and are more active in expressing opinions against the pandemic mandates.

In a clear example of this ‘rejection’ sentiment, a gym owner’s post discusses a form of injury common among older adults: “…let me tell you why my deemed ‘non-essential’ job is actually very much indeed ESSENTIAL. Because this [injury due to slips and falls] can be prevented and or minimized!!!” Although this message of being essential can serve to promote a service and attract clients, the term “essential” is used here not as a branding strategy, but rather to explain how balance training can reduce fall injuries. In this example, more attention is devoted to justifying why the business is essential, countering the government-defined “essential job” as being too narrowly defined and, therefore, unreasonable.

The fitness industry (gyms, dance studios, etc.) most frequently make claims about being essential. This might be a sign that fitness-related businesses tend to more firmly believe their business and services are essential in comparison to other non-essential businesses. The fitness industry generates 101 out of 136 data-posts in “claiming to be essential,” and 17 out of 44 in “refuting or redefining ‘essential.’” In contrast, the personal service industry (hairdressers, beauty salon, etc.) is the second most frequent with 16 posts in the former theme and 18 posts in the latter.

For fitness businesses whose posts are coded into the two essential theme-based categories, many of them address the narrative that “gyms are part of the solution to pandemic.” These accounts argue that exercising is an effective way to strengthen physical and mental health, which would result in stronger immunity against COVID-19. Therefore, in their view, closing fitness facilities defeats the purpose of stopping COVID-19 transmission and they deserve to be recognized as essential work.

Personal service businesses justify their essential service primarily for mental health reasons. For example, a hair salon claims “we are essential to mental health,” saying that “we don’t just cut hair, we are a friend to a lonely person, a confidant, a sounding board, and a connection to how a person feels about themselves!” This argument targets the merits of self-confidence and the familiarity of beauty routines that many people were forced to give up due to the lockdowns, and therefore further exacerbated mental wellbeing during the pandemic.

Normalizing “Essential” in Popular Discourse

The use of “essential” on Instagram is a snapshot of a prominent clash of interests between small businesses as an economic community and the government as the authority to manage the health crisis. The conversation around essential work has become more popular with the pandemic.

According to Google Trends, the term essential reached its peak popularity in Canada the week of March 22, 2020, with an increase of 90% from the week of March 8. This increase parallels the introduction of pandemic measures in Canada. Since then, there are spikes in popularity for the term “essential” that correlate timewise with new lockdown policies.

It would be understandable if the claim on essentialism is just a sign of the income struggle among small businesses during the lockdown. However, essentialism has been integrated by many anti-masker and anti-mandate groups. The organization WeAreAllEssential (WAAE) argues for all types of businesses to stay open, positioning all industries as “essential.” WAAE has organized several anti-mandate protests, including a protest in February 2021, where businesses across Canada opened regardless of provincial pandemic policies. Hugs Over Masks, another prominent Canadian anti-masker group, uses “Freedom is Essential” and “We Are All Essential” in their campaigns.

Throughout the pandemic, these groups and prominent anti-maskers have been criticized for their connection to the far-right. The Canadian Anti-Hate Network has outlined the antisemitism, racism, homophobia, and transphobia of prominent figures like Chris Sky, amongst others, who represent and propel anti-mandate movements. NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh has explicitly stated that groups and individuals protesting public-health guidelines as having common ground in an “extreme right-wing ideology.” This association between anti-maskers and far-right politics has only been furthered by the “Freedom Convoy” occupation of Ottawa, which was host to white supremacists, Nazis, and individuals who wished to overthrow the Canadian government.

It would be inaccurate to assign the label “anti-masker” or “far-right” to anyone who claims essentialism. Many of these businesses may be unaware of the connotations of the phrase “We are essential” beyond its popularity in arguing to reopen their businesses. However, it is important to note how language used by anti-mandate groups is adopted and used in normal populist discourse.

While our focus was on those who took up “essential” to situate their own business as an important service, we encountered 917 posts in our dataset that deployed the term “essential” or “We Are Essential” as a marketing tactic alongside promotional content for their brand. These posts have little to do with either the pandemic itself or essential work defined by the government, but leverage the momentum generated by #WeAreEssential to advertise services and products on the platform. This use of “essential” might potentially contribute to the normalization of the anti-mandate expression in popular discourse.

In comparison to the amount of promotional content, explicit criticism of pandemic policies is rare in our dataset, but it might not necessarily signify an absence of resentment. Rather, by including #WeAreEssential these posts on Instagram, even without making explicit comments towards the government and covid mandates, are aligning with ongoing movements in opposition to closure mandates. Consequently, these posts increase the visibility of #WeAreEssential as anti-pandemic discourse, while the seemingly non-political slogan and content allow the essential expression to be diffused and accepted easier by the wider public.

The current research does not specifically cover businesses’ avoidance of commenting on the pandemic issue, but, hopefully, the current findings could serve as an exploration of businesses’ pandemic discourse in response to pandemic policy and hint for further investigation.

A complete break down of our methodology is available on request.