Photo by Chris Cline

It covers 70 per cent of the planet’s surface and comprises 60 per cent of the average adult’s body weight. In utero, we float in a fluid that’s mostly water, and after we are born we must drink water or we will die.

Without it, plants would not grow or produce oxygen. It regulates the Earth’s climate and, like looking at fire, is mesmerizing to behold. Spending time in “blue space” — any aquatic environment, including oceans and lakes — has a psychologically restorative effect.

Water is how our ancestors travelled around the world and across continents, determining where most of our communities took root. And it cradles the Carleton campus, forking into the Rideau river and canal and flowing past the land upon which we work and play.

The ways that members of the university community engage with water vary tremendously, from pollution research and urban planning to marine mammal conservation. Several operate under the umbrella of Carleton’s Global Water Institute, a cluster of more than 100 researchers focused on addressing domestic and international water challenges.

“Water is essential — it is life,” says the institute’s director, Banu Örmeci, a Civil and Environmental Engineering professor and wastewater treatment expert. “It’s important for us to develop sustainable and appropriate solutions to the world’s water problems. We need to develop the right approach for the right location.”

Academics also need to ensure their efforts have tangible impacts, which is why the institute’s operations manager, Evan Pilkington, has been tasked with developing partnerships with government, industry and the non-profit sector. “In the broadest sense, water is a multidisciplinary issue,” he says, “and the university is uniquely poised to bring together disparate parties.”

Scroll down to see a small sprinkling of first-person stories that show our deep and diverse connections to an often overlooked yet vital and unifying resource.

- The Best Classroom: Inspiring the Next Generation of Water Protectors

- No Small Matter: The Spread (and Scourge) of Microplastics

- A Signal Amongst the Noise: Saving the Whales With Data Science

- Eyes on the Ball: An Athlete and Activist Finds Peace in the Pool

- Unfrozen: How Digging and Data Can Help Mitigate Permafrost Thaw

- Cash Flow: The Business of Canal Construction

- Resurrection: Bringing Our Riverside Heritage Back to Life

- Map Quest: Policy Change Through Storytelling

- On The Waterfront: Toronto’s Lakeshore Development Puzzle

- Take Me to the River: What my students learned from Pasapkedjiwanong

1. The Best Classroom

Inspiring the Next Generation of Water Protectors

Carleton PhD student Andrea Reid does research on Pacific salmon migrations, tracking the fish’s movement across space and time through threat-laden landscapes using techniques such as radio telemetry, and talking to Indigenous communities about changes they’ve observed — a challenging mix of ecological and social science. But Reid, a member of British Columbia’s Nisga’a Nation, believes it’s increasingly important to study natural systems in a holistic way and that a scientist’s impact should not be confined to academia. So even though she’s busy working on her thesis (which she hopes to finish next summer) and already has a job secured (as an Indigenous Fisheries Science professor at UBC), Reid and a pair of collaborators, Dalal Hanna and Mikayla Wujec — all three of whom are affiliated with National Geographic — have launched a non-profit, Riparia, that takes female-identifying youth on paddling trips with the goal of inspiring the next generation of water protectors.

Science has been a way for me to reconnect with my Indigenous heritage, which I grew up separate from on Prince Edward Island. But I grew up surrounded by water, fish and fishing communities, and the strong connections between fish, people and place instilled in me a massive amount of passion for this sort of work. Later, spending time in my second home, the territory of the Nisga’a Nation, which is where my father is from, I’ve come to learn that fish, people and place are truly indivisible. I now work precisely at this intersection — on conserving culturally-significant fish and fisheries by interweaving Indigenous and scientific knowledge systems and approaches.

Outdoor science during Riparia’s inaugural expedition to Poisson Blanc Regional Park two hours north of Ottawa. (Mikayla Wujec)

There’s no organization out there that we’re aware of like Riparia that pairs freshwater science with river expeditions for youth. Freshwater systems are often overlooked; oceans get all the glory. It’s also an extremely gratifying way to add value to my research — I’ve spent long, hard hours learning the fundamentals of freshwater ecology, limnology, fish dissection, radio telemetry and so much more — and now I get to distill my knowledge and skills into bite-size pieces and watch as they transform the youth who participate in our programs. My learning then stretches far beyond my thesis and these university walls.

Riparia is a passion project for Dalal, Mikayla and me. The Indigenous and non-Indigenous teens we bring on trips wouldn’t otherwise have access to these experiences. Our first expedition last summer was a five-day canoe circuit through the Poisson Blanc Regional Park two hours north of Ottawa. Most of the youth had not camped for that length of time before, nor had they carried all their gear on a multi-day trip. We canoed from site to site and spent each day looking at different freshwater issues. One day, for example, we focused on stream invertebrate sampling, so we paddled out to remote streams and started turning over stones and found tons of little crayfish and so many different organisms, like dragonfly larva, at various life stages. When we got back to camp, we took out our microscopes so the students could play around and get a whole new perspective on stream life. They loved it! Doing this outside of a lab setting removes intimidation because it’s all curiosity driven and fun.

In another activity, we tested water quality and talked a lot about the importance of water to people and to ecosystems. We had every tool we could get our hands on to measure every aspect of water — its temperature, depth, hardness, acidity, conductivity and more — many of which are based on chemical reactions. The youth would collect water samples off the sides of their canoes, then combine different chemicals in steps to see, for example, the amount of bromine or chlorine in the water. Seeing a chemical reaction in front of their eyes really pulled them in. The youth worked together as an amazing team.

Fundamental to people caring about the natural world is being able to spend time in it comfortably. The natural world is the best classroom there is. Outreach of this nature is a fantastic way to give back, while also sparking interest and curiosity in science in the next generation of potential scientists. For us, however, success doesn’t necessarily mean that our participants all go on to become scientists like us, but instead, we want to produce informed advocates who go on to champion science and stand up for freshwater protection in whatever path they follow.

Sampling microplastics pollution on the Ottawa River with the Ottawa Riverkeeper organization. (Martin Lipman/Ottawa Riverkeeper)

2. No Small Matter

The Spread (and Scourge) of Microplastics

Geography and Environmental Studies researcher Jesse Vermaire, who studies human impacts on freshwater ecosystems, has been collaborating with the Ottawa Riverkeeper organization, as well as students and citizen scientists, to sample microplastics pollution in the Ottawa River watershed. These tiny pieces of plastic are smaller than five millimetres in diameter and typically come from clothing, cosmetics and other everyday products. They can slip through wastewater treatment plants and may be eaten by fish and other animals.

A lot of people think the biggest concern is wildlife ingesting microplastics, which adversely affects not only their health but also our health if we eat them. But to me, just the fact that microplastics are everywhere, floating in the water and in the sediment, is hugely significant.

Microplastics are in snow in the Arctic and in really pristine lakes. They’re being transported in the atmosphere; we’re breathing them in. It’s a clear sign of human influence on ecosystems and has been proposed as a marker in the future geological record as the onset of the Anthropocene.

The microplastics issue is, to me, part of a larger concern around the sustainability of plastic use. We’re using millions of tons of plastic now every year and we don’t really know what to do with it. In Canada, we only recycle around nine per cent of it, and we landfill the bulk of it, which is really expensive, and a percentage of that — about one per cent of our plastic production — slips out as litter that breaks down into microplastics. We use so much plastic, that one per cent really adds up.

There has been some progress, such as Canada’s ban on microbeads — tiny plastic particles that were often added as exfoliates to personal care products. It took just one study in the Great Lakes for both government and industry to take steps, and in two years there was a ban. That’s exceptionally fast compared to how we’re responding to climate change and other environmental problems.

There is huge public interest in plastic pollution right now and there are great opportunities to tackle this problem. I think that’s because there’s no debate on where plastic comes from —humans — and because there’s no benefit to its presence in nature.

Reducing the amount of plastic we use is the first step toward reducing plastic pollution. But we can also improve and harmonize our recycling facilities, so it’s easier for producers to make plastics that can be recycled. And we can also improve our wastewater and storm-water systems, with better filters and other engineering solutions, to reduce the flow of plastic. Knowing how much is out there is an important foundation for all this work.

British Columbia killer whales. (Jeremy Koreski)

3. A Signal Amongst the Noise

Saving the Whales With Data Science

Dave Campbell, a statistics professor at Carleton, studied environmental science as an undergraduate. He loves the natural world and wanted to work in that realm, but despite his passion, his lab science marks weren’t great — but his stats marks were strong. That sent Campbell in a new direction. His research today varies tremendously, from developing machine learning frameworks that can process decades of eagle’s nest webcam footage to identifying problems with BC Ferries scheduling and looking for regional differences in how Canadians describe beer. But like a project he started last year with collaborators from Simon Fraser University and Dalhousie University, much of it has environmental applications.

The southern resident killer whale population — there are only about 70 of them — tends to spend its time around the southern tip of Vancouver Island and in the Salish Sea. This is a very busy shipping area. With a Department of Fisheries and Oceans grant, we’re trying to figure out how best to monitor the whales to predict where they’re going, so we can alert ships to slow down or take evasive action and avoid colliding with whales.

The whales are monitored in different ways, including underwater microphones called acoustic hydrophones and sighting logs from whale watching tours. We’re trying to combine data of mixed quality from a variety of sources, and factor in information such as whether they’re near a feeding ground, so we can make real-time predictions about their location and the direction and speed of their movements.

My expertise is in computational methods and uncertainty models, whereas my collaborators bring oceanographic and marine mammal backgrounds, and as with a lot of data science, domain-specific information needs to get folded into the analysis. But this work could help these whales, and the methods we develop could be applied to other whale or animal populations in other parts of the world.

In data science, there’s often quite a bit of signal amongst the noise — and if we can account for the noise and decode the signal, we can make decisions that offset all kinds of problems. I talk to really smart people about the challenges they face and look for opportunities to provide statistical insight in areas where data is available in one form or another. I’ve worked with companies in the past where our goal was to get people to buy more stuff, which seems to be the most funded problem in data science, if not the world. There are a lot of ways that we can use our data superpowers for social and environmental good, and these kinds of projects provide excellent training opportunities for students. Statistics and data science are exceedingly employable fields right now.

Waneek Horn-Miller

4. Eyes on the Ball

An Athlete and Activist Finds Peace in the Pool

Waneek Horn-Miller, a recent inductee into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame who graduated from Carleton with a political science degree in 2000, is famous for two main reasons. She was a water polo star, leading the university to a pair of provincial championships and representing Canada at the 2000 Olympics, the first time a female Mohawk athlete competed in the games. This accomplishment is made more impressive by the fact that a decade earlier, at age 14, Horn-Miller almost died when she was stabbed in the chest by a soldier’s bayonet during the Oka Crisis, a standoff over development on traditional Mohawk land.

I learned to swim at Carleton when I was four or five. My mom put us into swimming lessons because she wanted us to have big dreams and goals, but also to have perseverance and to work hard. She wanted us to learn that through sport, but not be in judged situations. She wanted us to race against the clock. That’s how I got into competitive swimming. By age 13, that got boring.

My oldest sister was playing water polo for her high school team, so I tried out and then tried out for the city team, whose coach also coached at Carleton. I didn’t know what I was doing but I loved it. I was a swim sprinter, so racing for the ball was not a problem.

I wanted to be a part of a team. To be part of a collective. And it was cool to be a trailblazer. There haven’t been a ton of Indigenous athletes on university or national teams. When you’re in it, it can be hard and lonely and challenging. You feel like you’re on the outside looking in and are trying to make other people understand you. We fear diversity in sport and society sometimes, but on teams you need diversity. You need people with different strengths to work together for a common goal.

There’s something about the weightlessness of water that I’ve always loved, but also something about playing water polo that makes you focus on the present. If you don’t focus on the present, you drown. All of the responsibilities that I’ve carried in my life, whether real or imagined, I was able to park them for a while when I was in the water and just enjoy that feeling of flow. From an Indigenous perspective, water is the first medicine. It’s one of the most sacred elements in our culture. Now that I’ve given birth and carried three children, I feel an even stronger connection to water. There’s not an English word for it — it’s just a beautiful place for me to be.

PermafrostNet data scientist Nick Brown got the hang of fieldwork before going back to school. (Stephan Gruber)

5. Unfrozen

How Digging and Data Can Help Mitigate Permafrost Thaw

Last year, to help Canada adapt to thawing permafrost, NSERC created the $5.5-million Permafrost Partnership Network, or PermafrostNet. Led by Carleton climate change researcher Stephan Gruber, the network brings together scientists from a dozen universities and more than 40 partner organizations, including industry, Indigenous communities and government agencies, nationally and internationally. Permafrost is ground that remains at or below zero degrees for two years or more, creating a unique environment that permits the preservation of buried ice. PermafrostNet’s data scientist, Nick Brown, who met Gruber while running a fly-in geological services field camp on the tundra east of Yellowknife and later did his master’s degree with Gruber, explains how the new network will address one of climate change’s biggest challenges.

After my undergrad, I went north for a summer in 2012 and moved up permanently the following year, staying until 2015. I helped teams do everything from drilling core samples to doing geophysical surveys to moving hundreds of fuel drums by helicopter. We also compiled a lot of the geoscience data, analyzing it and creating reports. I love doing fieldwork in these remote places and getting an understanding of the science behind it.

Some people tend to focus more on fieldwork and others more on modelling and data analysis, and there are big strengths to both ways of studying phenomena such as permafrost, but a blended approach can also be very effective. Stephan’s research program combines a strong fieldwork component with computer simulations using big data sets. PermafrostNet has been set up to help field scientists and data modellers collaborate, and to harness the data sets that various agencies have already collected. My role is to help make this happen.

Permafrost is important in both a global and Canadian context. Within Canada, thawing permafrost has tremendous implications for any sort of northern infrastructure — roads, pipelines, airports — and northern ways of living. Highways buckle and heave, houses sink, and pipelines and other linear infrastructure are particularly susceptible. Globally, as it thaws, carbon emissions are projected to increase. There are still questions about how much carbon is stored and what form it’s in, but we know that permafrost plays a significant role in the climate feedback system.

Some permafrost can have a significant amount of ice in it — as layers, veins or wedges of ice, which arise from the repeated contraction of the ground producing cracks that fill with water, a process that’s repeated year after year. When this ice melts, you can get dramatic landscape changes, especially if there’s a slope to the ground and large thaw slumps develop. More often though, these impacts are much less visible, unlike shrinking glaciers. This hidden nature makes PermafrostNet’s national-scale simulations and forward-looking models an important tool. But having been up north and seen some of these changes firsthand still provides the best motivation.

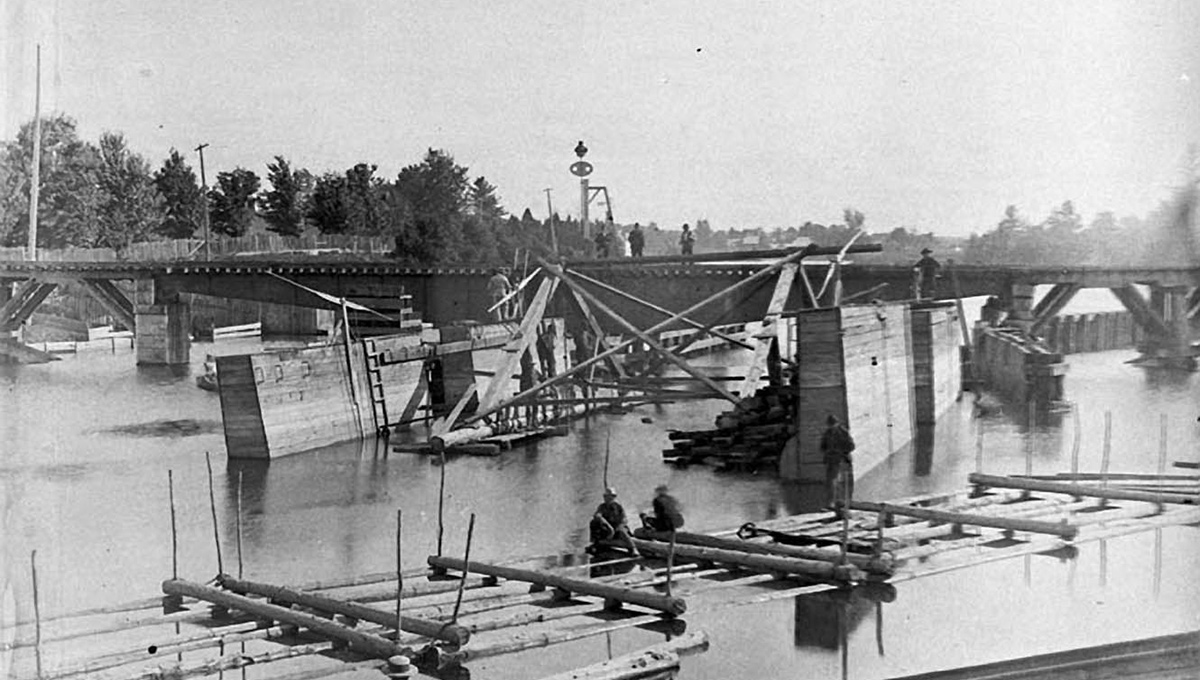

Rideau Canal construction. (Library and Archives Canada/N. Bruce Ballantyne Collection)

6. Cash Flow

The Business of Canal Construction

To most people, the Rideau Canal is something to skate on in winter and something to walk, run or cycle beside in summer. Merridee Bujaki, an accounting professor at Carleton’s Sprott School of Business, has a different take on the UNESCO World Heritage Site. For the past dozen years, she’s been working on a multifaceted accounting history of the canal, publishing academic papers that explore, for example, early budget estimates and cost-benefit analyses in correspondence about the project.

I’ve lived almost my entire life at one end of the canal or the other, either in Ottawa or Kingston. I’ve always been fascinated by its history, and nobody had really looked at it from an accounting perspective before. I knew there had been overspending when it was built, but I was curious about the nitty gritty details, such as what kind of spending controls were in place. Accounting information provides a really good record of the challenges that were encountered. It’s a record of the planning process, the evolution of management practices, the relationship between the British royal engineers who designed the canal and the contractors who built it, and even of the portrayal of Indigenous peoples.

I see strong links between this history and contemporary construction projects, including the new LRT system in Ottawa. The language and rhetoric that’s used to describe these big infrastructure projects is actually quite similar, even though it’s 200 years later. We can learn lessons from the past, such as knowing that you’re going to encounter challenges when you start digging and should factor uncertainty around costs and timelines into your plans in a formal way.

The thing this project brings me back to again and again is the importance of water. All of our major cities and towns are on water, but when you listen to traffic reports on the radio, commuters backed up in their cars on bridges, water is often an impediment. Yet historically, waterways were fundamental mechanisms for connecting people and places. They were the main transportation routes. Some archival British government documents even call the Rideau Canal an inland communication. A noun, not a verb. There’s a really expressive and eloquent way that people wrote in the 1800s, albeit for persuasive purposes. You never know what you’re going to find in the archives, things that might otherwise stay buried.

Doing digital documentation work at the Ottawa River Boathouse. (Mariana Esponda)

7. Resurrection

Bringing Our Riverside Heritage Back to Life

The first time architecture professor Mariana Esponda walked up to the Ottawa River Boathouse — a century-old, three-storey, gable-roofed heritage building perched over the water on stilts in the east end of the city — she was struck by the interplay between the structure and the natural setting. Inside, she noticed both the building’s dilapidated conditions and its strong bones. Esponda, who seeks projects for students that involve real-world clients and problems, immediately knew that she wanted to help bring life back to a site that has hosted regattas and raucous dances for decades, most recently as the home of the Ottawa New Edinburgh Club. Her students spent months digitally documenting the pavilion and painstakingly creating 13 detailed proposals for its future use — creative designs that informed the National Capital Commission’s ongoing multimillion-dollar revitalization effort, which will preserve the landmark building and transform the space into a four-season facility that welcomes people back to the riverside.

There’s a real feeling of discovery in that building. Every time you turn around, you get a different view and have a different relationship with the water. Sure, it’s been neglected — the paint is peeling, there is oxidation on the metal — but there’s a beauty to that as well. It’s the aging of the building. The upper floor is a huge open space, surrounded by windows, with doors to a balcony. When you step outside, it’s magical. And then you go down to the lowest level, where the club’s kayaks and canoes are stored, and onto the docks, and you are floating. You are part of the river.

I wanted the students to understand the connections between the building and the waterway, and to enhance its environmental and historic values. The building is a testament to early-20th century recreation. It was a place for community, and that’s something we’re losing. I wanted them to re-imagine that era, and also to think about things like the location’s Indigenous history, native vegetation and animal species, water treatment, and accessibility from the shore. Collectively, their proposals became kind of a master plan. The National Capital Commission saw the possibilities for what it could become and showed our drawings and designs to potential partners, for everything from conservation and stabilization to commercial uses. What the students proposed is going to become real.

When we started working on this, in spring 2017, there was major flooding, and there was flooding again last spring. The students are very aware of how climate change is affecting this site, and aware that we have to respond. When people come and enjoy this area, they’ll have more of a sense of stewardship. Many people in Ottawa don’t know this amazing location. The best way to protect a place is to use it. If we don’t give life to it, nobody is going to care and it’s going to be forgotten.

Tractor machine plows the fertile farm in Salinas Valley, California.

8. Map Quest

Policy Change Through Storytelling

Sheryl-Ann Simpson, who joined Carleton last year from the University of California, Davis, does research at the intersection of urban planning, environmental justice and health, exploring the role of government in our everyday lives. How, her work asks, are municipal laws made? How can policy support equity? While in California, she was approached by the Community Water Center (CWC), which supports the right to safe, clean and affordable water. The CWC wanted help making a map that linked access to water to health concerns, leading to an ongoing collaboration with Simpson that she has brought to Carleton.

There is a lot of inequality in California, which is related to the fact that there are so many vulnerable migrant workers, including a large Mexican-American population, in the state. This inequality has been exacerbated by climate change. Groundwater has been drained off by agricultural practices, which has multiplied the impacts of drought. Wells went dry or were contaminated, but because there wasn’t enough oversight people kept drinking this water. This can contribute to incidence of certain types of childhood cancers, to premature births and low birthweights, which are some of the things that the CWC asked me to map.

There’s a long history of using this type of approach to measure problems in a community, because quantitative tools generally have a lot of sway with policymakers. But maps aren’t always sensitive enough to actually register what people are seeing and saying, and a lot of health concerns are long term and cumulative — and they’re not only related to drinking water but could also be connected to the water you bathe in, the water you use to clean your fruit, the water you’re using or the chemicals you’re exposed to in your agricultural job. You can’t always get at these relationships with conventional data gathering, so we’re trying to make maps that are also qualitative, and we’ve discovered links between water contamination and health markers such as low birthweights.

Right now, I’m working with an interdisciplinary team — it includes an environmental policy analyst, a public health nurse, another health geographer, a public policy specialist and two of my undergraduate students — to build qualitative tools that capture people’s stories and experiences and are also legible to policymakers. We’re trying to translate people’s experiences into something that policymakers can understand and, more important, take action on.

California is a canary in the coalmine. Drought, fires, pollution, poor air quality — the impacts of climate change are being felt more strongly there, and these things all feed back into health questions. California has pretty much the same population as Canada, so paying attention to how communities there adapt could have lessons for us.

The Simcoe WaveDeck at Queens Quay in downtown Toronto. (Waterfront Toronto)

9. On The Waterfront

Toronto’s Lakeshore Development Puzzle

Last fall, as Google subsidiary Sidewalk Labs’ controversial plan to develop a high-tech district on the lakeshore in downtown Toronto moved through the approvals process, Waterfront Toronto emerged as an important watchdog. Created in 2001 by the federal, provincial and municipal governments to revitalize 2,000 acres of former industrial land beside Lake Ontario, Waterfront Toronto is currently evaluating the Sidewalk Labs proposal, including questions around data privacy. It’s all part of the challenge of creating sustainable mixed-use communities and public spaces in a mega city — and another day’s work for George Zegarac, a Carleton Master’s of Public Administration graduate and 33-year senior provincial government official who became the president and CEO of Waterfront Toronto last summer.

This part of Toronto was once a large manufacturing area. The lake was used for transportation and industry. It is no longer the industrial hub it once was. When the city was bidding to host the 2008 Olympics — which went to Beijing — there was a lot of excitement about redeveloping the waterfront. That catalyzed all three levels of government, who created Waterfront Toronto to work with public and private partners and oversee the revitalization. The main focus from the start was to give everybody access to the waterfront: to build complete communities with affordable housing, to build and improve parks and other public spaces, to create places to live and work and play.

I spent nine years with the province’s Ministry of the Environment and helped create the Ontario Clean Water Agency almost 30 years ago. That was about finding a transformative way to protect our environment, and I’ve been intrigued by transformational opportunities throughout my career. That’s what really attracted me to Waterfront Toronto. As CEO, I have to make sure that we follow the direction of our board and partners, and make sure we secure appropriate funding to build world-class projects. We get input from all three levels of government, but engaging with the public is our top priority. We need to ensure that a variety of community voices are embedded in early discussions about any development.

When I started this job, I got on my bike and rode along the waterfront. There are municipal gardens, art installations and ferries to the Toronto Islands. Beside the old sugar refinery, there’s Sugar Beach, which has gorgeous sand and big umbrellas and a promenade with beautiful trees. It’s a great place for de-stressing, and now companies, shops and a college are moving into the area. I don’t think people realize how much the city’s waterfront has changed and how much potential it has. Which is why it’s so important to get things right.

The Rideau River flows past the Carleton campus. (Victoria Ricciardelli)

10. Take Me to the River

What my students learned from Pasapkedjiwanong

Carleton’s Collaborative Indigenous Learning Bundles project — one of the university’s responses to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action around integrating Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into post-secondary institutions — has led to the creation of a series of focused Indigenous knowledge modules that are available for faculty to deliver in their classes. The Bundles provide the factual and theoretical basis for understanding Indigenous history and politics in Canada, while prompting students to consider how this knowledge might be applied in their areas of study. English professor Janice Schroeder shares an account of using one of the Bundles with her students.

The Bundle on Indigenous environmental relations doesn’t include English in its list of possible courses. Yet its knowledge keeper, Kitigan Zibi elder Albert Dumont, is a poet and author of a children’s book. He works in genres we study regularly in English. Indigenous literatures and, increasingly, environmental awareness inform our English courses at Carleton. So I decided to introduce the Bundle last September in a required course I’ve taught for years on 18th- and 19th century British literature. That was the era of the so-called Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, the age of global colonial expansion, and the period that spawned some of the first examples of environmental writing in English. The Bundle helped decentre western conceptions of “nature” expressed in the texts we had been discussing. It also led us outside the classroom to the side of Pasapkedjiwanong.

I learned from Bonita Lawrence’s excellent book Fractured Homeland that Pasapkedjiwanong means “the water that runs between the rocks.” When Samuel Champlain renamed it the Rideau River, he performed an act of colonial erasure — one of many. Part of the great Kiji Sibi (or Ottawa River) watershed, Pasapkedjiwanong holds Indigenous stories that are not mine to tell. But prompted by the Bundle, I asked my students to follow me outside on a beautiful autumn morning, to sit quietly by the river, to listen to its voice, to observe its movements and inhabitants, and to reflect on their relationship to the river.

I asked them if they had ever really considered this river before. Did they know its settler or its Algonquin name? I asked my students what it means to study at Carleton, which is nestled between Pasapkedjiwanong and the Rideau Canal, a colonial nation-building project that permanently altered the river’s original path. When we say before events that “Carleton University is located on unceded Algonquin territory,” do we understand the implications? Does the river that runs past our campus have anything to teach us? One student later reflected that, although initially skeptical about learning from the river, she has begun to see how Indigenous values of relationality and reciprocity between human and more-than-human agents could reshape her understanding of literature.

The teachings shared by Métis/Otipemisiw anthropology professor Zoe Todd in this Bundle challenge us to think about rivers, trees and other species as “parts of society.” One thing this could mean for us in English — or any program — is questioning the division between nature and culture that structures knowledge in the western university. In his response to the Bundle, one student later described cherished memories of his family’s cottage. “I don’t remember ever discussing with my family which people’s traditional land the cottage was built on,” he said. My hope is that he takes the time to find out.