We must remember. If we do not, the sacrifice of those one hundred thousand Canadian lives will be meaningless. They died for us, for their homes and families and friends, for a collection of traditions they cherished and a future they believed in; they died for Canada. The meaning of their sacrifice rests with our collective national consciousness; our future is their monument.1

These wars touched the lives of Canadians of all ages, all races, all social classes. Fathers, sons, daughters, sweethearts: they were killed in action, they were wounded, and thousands who returned were forced to live the rest of their lives with the physical and mental scars of war. The people who stayed in Canada also served—in factories, in voluntary service organizations, wherever they were needed.

Canadian National

Vimy Memorial

Yet for many of us, war is a phenomenon seen through the lens of a television camera or a journalist’s account of fighting in distant parts of the world. Our closest physical and emotional experience may be the discovery of wartime memorabilia in a family attic. But even items such as photographs, uniform badges, medals, and diaries can seem vague and unconnected to the life of their owner. For those of us born during peacetime, all wars seem far removed from our daily lives.

We often take for granted our Canadian values and institutions, our freedom to participate in cultural and political events, and our right to live under a government of our choice. The Canadians who went off to war in distant lands went in the belief that the values and beliefs enjoyed by Canadians were being threatened. They truly believed that “Without freedom there can be no ensuring peace and without peace no enduring freedom.”2

By remembering their service and their sacrifice, we recognize the tradition of freedom these men and women fought to preserve. They believed that their actions in the present would make a significant difference for the future, but it is up to us to ensure that their dream of peace is realized. On Remembrance Day, we acknowledge the courage and sacrifice of those who served their country and acknowledge our responsibility to work for the peace they fought hard to achieve.

During times of war, individual acts of heroism occur frequently; only a few are ever recorded and receive official recognition. By remembering all who have served, we recognize their willingly-endured hardships and fears, taken upon themselves so that we could live in peace.

Soldiers from the First Canadian Paratroopers Batallion shortly after the Normandy landing on June 6, 1944.

Whom Do We Remember?

As the artillerymen swung three abreast down Main Street, traffic stopped and people watched from the sidewalks. Some stood in silence. A few wept. Some cheered a bit or called out to soldiers they knew—to an officer who had for years devoted his spare time to the militia battery, to a genial giant from the slums, to a farmboy from Taylor Village, to a man with a police record, to a teenager leaving the prettiest girl in town.3

When war has come, time and again Canadians have been quick to volunteer to serve their country. From farms, small towns and large cities across the country, men and women signed up, motivated by reasons like patriotism, ideological belief, family tradition, the seeking of adventure, or just to escape unemployment. They join Canada’s war effort prepared to defend, to care for the wounded, to prepare materials of war, and to provide economic and moral support.

War has always meant death, destruction, and absence from loved ones. But in the initial surge of patriotic fervour, these play a secondary role. For the men and women who rally to support their nation’s cause, the threats of war seem far away and unreal. For example, in the fall of 1914, as the First Contingent of Canadians left the shelter of the St. Lawrence for the open Atlantic, some of the realities came into focus. Nursing Sister Constance Bruce wrote:

Those who came forward had not stopped to count the cost, for the excitement was thrilling, the lottery alluring, and the cause glorious; but now that the confusion was passed, and the fulfilment of vows alone remained to be faced, things took on a more sombre aspect ….4

How could they have known that four long years of death and destruction were ahead?

Again, in 1939 when the mobilization orders came for the Second World War, Canadians flocked to enlist. The new troops included Veterans of earlier wars, boys still in high school, and thousands of unemployed. The recruits came from many regions and from varied backgrounds. Eighteen-year-old Aubrey Cosens, a railway section hand at Porquis Junction, Ontario, was rejected by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), but did get into the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Robert Gray joined the Navy as soon as he graduated from the University of British Columbia. John Foote, a 35-year-old Presbyterian minister, joined the chaplain corps. All were typical Canadians and all distinguished themselves by earning the Victoria Cross.

Even while immersed in the brutality of the war, some men take time to question the forces that bring the hostility between countries to such terrible ends, and to ask whether life can ever return to normal. Donald Pearce wrote these words from a front line dugout:

When will it all end? The idiocy and the tension, the dying of young men, the destruction of homes, of cities, starvation, exhaustion, disease, children parentless and lost, cages full of shivering, starving prisoners, long lines of civilians plodding through mud, the endless pounding of the battle-line.5

Those who experienced the blood and carnage of battle believed that their efforts had made the world a safer place. Yet only a few years after the end of the Second World War, Canadians were again called to uphold the cause of peace and freedom. From 1950 to 1955, Canadian men and women served under the United Nations flag in Korea. They included new recruits as well as Veterans from the previous war. Along with various army units, the navy and the air force provided vital support and endured months of hardship in the hope of maintaining world peace.

Since the end of the overt hostilities in Korea some 60 years ago, Canadian soldiers have come to play a different, yet essential, role on the world stage. Our commitment and skills as peacekeepers has gained Canada respect and influence the world over.

For all of these conflicts fought in far-off lands, there is much to remember. Foremost are the people, the men and women who served wherever they were needed. They faced difficult situations bravely and brought honour to themselves, to their loved ones and to their country. They were ordinary Canadians who made extraordinary sacrifices.

Nursing Sisters of No. 10 Canadian General Hospital, RCAMC landing at Arromanches, France, July 23, 1944.

What Should We Remember?

Formal records tell us about the size and strength of armies, military strategy, and the outcome of battles. Such information is vital, yet to fully appreciate military history we must try to understand the human face of war. Loss of comrades, extreme living conditions, intense training, fear, as well as mental, spiritual and physical hardship helps illuminate what the individual sailor, soldier and airman experienced in battle.

The First World War 1914-1918

In the First World War, the Canadians’ first major battle occurred at Ypres, Belgium, on April 22, 1915, where the Germans used poison gas. As approximately 150 tonnes of chlorine gas drifted over the trenches, Canadian troops held their line and stopped the German advance in spite of enormous casualties. Within 48 hours at Ypres and St. Julien, a third of the Canadians were killed. One of those who survived described the aftermath of a dreaded gas attack:

The room was filled with dying and badly wounded men; trampled straw and dirty dressings lay about in pools of blood. The air, rank with the fumes of gas, was thick with the dust of flying plaster and broken brick, and stifling with the smoke from the burning thatch.6

Using outdated 19th century military strategy, Allied generals believed that sending wave after wave of infantry would eventually overwhelm the enemy. Soaring casualty rates proved that soldiers attacking with rifles and bayonets were no match for German machine guns. Each side dug in and soon the Western Front became a patchwork of trenches in France and Belgium stretching from Switzerland to the North Sea.

In April 1917, Canadians helped turn the tide of battle when they won a major victory at Vimy Ridge. This triumph came at high cost: more than ten thousand casualties in six days. Even with this victory, the war continued for more than a year. Finally, on November 11, 1918, the Armistice was signed and the Canadians took part in the triumphant entry into Mons, Belgium. Throughout this conflict, Canadians proved that they could pull their weight, and by their effort earned for Canada a new place among the nations of the world.

A company of Canadian soldiers go “over the top” from a World War I trench.

The Second World War 1939-1945

During the Second World War, Canadians fought valiantly on battlefronts around the world. More than one million men and women enlisted in the navy, the army and the air force. They were prepared to face any ordeal for the sake of freedom. When the war was over, more than 42,000 had given their lives. On the home front as well, Canadians were active as munitions workers, as civil defence workers, as members of voluntary service organizations, and as ordinary citizens doing their part for the war effort.

In December 1941, Canadian soldiers were participants in the unsuccessful defence of Hong Kong against the Japanese; 493 were wounded and 557 were killed in battle or at the hands of the Japanese as prisoners-of-war (POWs). The situation faced by the Canadian POWs was horrible; they laboured long hours and were given very little to eat. The daily diet was rice—a handful for each prisoner. Occasionally, a concoction of scavenged potato peelings, carrot tops and buttercups was brewed. The effect was obvious:

Sidney Skelton watched the 900-calorie-a-day diet shrink his body from 145 to 89 pounds. And whenever a group of prisoners could bribe a guard into giving them a piece of bread , they used a ruler to ensure everyone got an equal share.7

Canadians played a leading role on the European front. On August 19, 1942, Canadians attacked the French port of Dieppe. Canadians made up almost 90 per cent of the assault force. The raid was a disaster. Out of a force of 4,963 Canadians, 3,367 were killed, wounded, or became POWs. Lucien Dumais was there and described the beach upon landing:

The beach was a shambles, and a lot of our men from the second wave were lying there either wounded or dead. Some of the wounded were swimming out to meet our flotilla and the sea was red with their blood. Some sank and disappeared. We stood by as they died, powerless to help; we were there to fight, not to pick up the drowning and the wounded. But the whole operation was beginning to look like a disaster.8

Canadians played an essential role as the war continued. They participated in the conquest of Sicily in 1943, and defeated the Nazis in Italy despite fierce resistance especially at Ortona and Rimini. On June 6, 1944, D-Day, Canadians were in the front lines of the Allied forces who landed on the coast of Normandy. All three Canadian services (navy, army, and air force) shared in the assault. In Normandy, the fighting was fierce, and the losses were heavy. Approximately 14,000 Canadians landed on Juno Beach and suffered 1,074 casualties (including 359 fatalities).

Canadians encountered fierce resistance from the German occupiers as they fought through Northwest Europe, particularly at Caen and Falaise, France, as well as the formidable task of clearing the English Channel ports in France and Belgium. They also saved the Allied advance from stalling by defeating the Nazis in the Scheldt estuary of Belgium and Holland—intense fighting over flooded terrain.

In May 1945, victory in Europe became a reality and millions celebrated V-E Day. Still ahead lay the final encounter with Japan. Then, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, a second bomb destroyed Nagasaki. On August 14, 1945, the Japanese accepted the Allied terms of unconditional surrender and the Second World War was over.

D-Day: Canadian soldiers disembarking on Juno Beach during the Battle of Normandy.

The Korean War 1950-1953

The hard-fought end to the Second World War did not provide Canadian troops with a long peace. By 1950, Canadian soldiers were mobilized on behalf of the United Nations (UN) to defend South Korea against an invasion by North Korea. By 1951, the People’s Republic of China had joined North Korea against the UN force. In Korea, the Canadians fought at Kapyong, at Chail-li, in the advance across the Imjin River, and in the patrolling of the Chorwon Plain. When the hostilities ended in 1953, Canadians stayed as part of the peacekeeping force.

The conditions in Korea were often difficult, with harsh weather, rough terrain, and an elusive and skillful enemy. In their own camp, they had to deal with casualties, illness and limited medical facilities. The winter of 1951 was especially severe. They were living twenty-four hours a day in trenches, which provided some protection but little comfort. As one soldier recalled, the weather aggravated what was already a demoralizing experience:

Rain was running down my neck, my hands were numb, and I never seemed to be dry. Kneeling in the snow, or advancing in the rain, my knees and the front of my legs became wet. Then the dampness soaked right through and the skin underneath became tender and raw.9

Altogether, 26,791 Canadians served in the Korean War and approximately 7,000 continued to serve between the cease-fire and the end of 1955 when Canadian soldiers were repatriated home. There were 1,558 casualties, 516 fatal. While Canada’s contribution formed only a small part of the total United Nations effort, on a per-capita basis, it was larger than most of the other nations in the UN force.

“It (Canada’s participation in Korea) also marked a new stage in Canada’s development as a nation. Canadian action in Korea was followed by other peacekeeping operations which have seen Canadian troops deployed around the world in new efforts to promote international freedom and maintain world peace.”10

From all of these records of wars, the observations of the individuals who took part stand out as reminders of the true nature of conflict. Through knowledge of the realities, we may work more diligently to prevent them from happening again.

Sergeant Tommy Prince (second left) with Major George Flint and other officers of 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry prior to a 1951 patrol. Prince, an Indigenous soldier from Brokenhead Ojibway Nation (also known as Scanterbury), was one of Canada’s most decorated soldiers.

Canada in Afghanistan

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) conducted operations in Afghanistan for more than 12 years in a number of different roles involving air, land and sea assets.

Since the beginning of the mission, more than 40,000 CAF members deployed to Afghanistan, many more than once, making the military engagement the largest deployment of CAF personnel since the Second World War.

On May 9, 2014, Canadians were invited to take part in the National Day of Honour. The Government of Canada set aside this day to mark the end of our country’s military mission in Afghanistan. A national ceremony on Parliament Hill paid tribute to the fallen, the sacrifices of the wounded, and the special burden borne by families. Between 2001 and 2014, 159 Canadian soldiers died while on mission in Afghanistan. Additionally, more than 2000 soldiers were injured during the war between April 2002 to December 2011. 635 soldiers were injured in action while 1412 were injured in patrol or non-combat situation. Canada has suffered the third-highest absolute number of deaths of any nation among the foreign military participants, and one of the highest casualties per capita of coalition members since the beginning of the war.

5 August 2006: Ramp Ceremony held at Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan. Corporal Christopher Jonathan Reid Corporal Bryce Jeffrey Keller, Private Kevin Dallaire, and Sergeant Vaughan Ingram. All were from the Edmonton-based 1 Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. (Photo by: Master Corporal Lester Budden)

How Do We Remember?

On November 11, especially, but also throughout the year, we have the opportunity to remember the efforts of these special Canadians. In remembering, we pay homage to those who respond to their country’s needs. On November 11, we pause for two minutes of silent tribute, and we attend commemorative ceremonies in memory of our war dead.

Following the First World War a French woman, Madame E. Guérin, suggested to British Field-Marshall Earl Haig that women and children in devastated areas of France could produce poppies for sale to support wounded Veterans. The first of these poppies were distributed in Canada in November of 1921, and the tradition has continued ever since, both here and in many parts of the world.

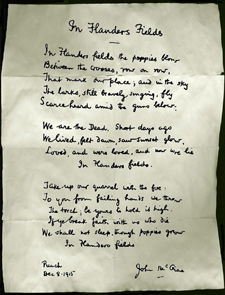

In Flanders Field, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae

Poppies are worn as the symbol of remembrance, a reminder of the blood-red flower that still grows on the former battlefields of France and Belgium. During the terrible bloodshed of the second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, a doctor serving with the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, wrote of these flowers which lived on among the graves of dead soldiers:

In Flanders Fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

John McCrae 11

The flowers and the larks serve as reminders of nature’s ability to withstand the destructive elements of war by men, a symbol of hope in a period of human despair. In Canada, traditionally the poppies which we wear were made by disabled Veterans. They are reminders of those who died while fighting for peace: we wear them as reminders of the horrors of conflict and the preciousness of the peace they fought hard to achieve.

There are 848 Canadians buried in the Adegem Canadian War Cemetary in Belgium including members of the 3rd Canadian Division, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the 52nd Division.

The two minutes of silence provide another significant way of remembering wartime while thinking of peace. Two minutes are scarcely enough time for thought and reflection. As we pause and bow our heads, we remember those brave men and women who courageously volunteered for the cause of freedom and peace.

For those who lived through these wars, remembering means thinking of comrades. It evokes memories of men and women who never returned home. Those born after the wars might picture the youthful soldiers who eagerly joined up from high schools, businesses and farms across the country, only to meet death while fighting against the enemy. They may imagine the anguish of a man leaving a new wife, a young family, an elderly mother. The important thing for all of us to remember is that they fought to preserve a way of life, Canadian values, and the freedom we enjoy today and often take for granted. Remember that the silence is to honour their sacrifice and memory.

There are memorials to commemorate the service of Canadian troops in Canada and overseas. The National War Memorial in Ottawa was originally designed to recognize those who served in the First World War. It has been rededicated to symbolize the sacrifice made by Canadians in the Second World War, in Korea, and in subsequent peacekeeping missions. The National War Memorial symbolizes the unstinting and courageous way Canadians give their service when values they believe in are threatened. Advancing together through a large archway are figures representing the hundreds of thousands of Canadians who have answered the call to serve; at the top of the arch are two figures, emblems of peace and freedom.

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is located next to the National War Memorial and contains the remains of an unknown Canadian First World War soldier who was exhumed from a cemetery near Vimy Ridge. The Tomb and its Unknown Soldier represents all Canadians, whether they be navy, army, air force or merchant marine, who died or may die for their country in all conflicts—past, present, and future.

The Books of Remembrance which lie in the Memorial Chamber of the Peace Tower are another record of the wars. In addition, most cities and towns across the country have dedicated a monument, a building, or a room to their native sons and daughters who gave their lives. These commemorative locations are an enduring record of the losses suffered by communities as Canadians went forward to fight for what they believed was right.

One day every year, we pay special homage to those who died in service to their country. We remember these brave men and women for their courage and their devotion to ideals. We wear poppies, attend ceremonies, and visit memorials. For one brief moment of our life, we remember why we must work for peace every day of the year.

The Netherlands fell to the Germans in May 1940 and was not re-entered by Allied forces until September 1944. The great majority of those buried in Holten Canadian War Cemetery died during the last stages of the war in Holland, during the advance of the Canadian 2nd Corps into northern Germany, and across the Ems in April and the first days of May 1945. After the end of hostilities their remains were brought together into this cemetery. Holten Canadian War Cemetery contains 1,393 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War.

References:

- Heather Robertson, A Terrible Beauty, The Art of Canada at War. Toronto, Lorimer, 1977.

- King George VI at dedication of National War Memorial, Ottawa, May 21, 1939.

- The Canadians at War 1939/1945. Volume One. Montreal, Reader’s Digest, 1969. Excerpt referring to the departure of the 8th Battery of the Royal Canadian Artillery from Moncton, N.B.

- Constance Bruce, Humour in Tragedy: Hospital Life Behind 3 Fronts by a Canadian Nursing Sister. London, Skeffington, n.d.

- Donald Pearce, Journal of a War: North-West Europe, 1944-1945. Toronto, Macmillan, 1965.

- George Herbert Rae Gibson, Maple Leaves in Flanders Fields. Toronto, Briggs, 1916.

- Ted Ferguson, Desperate Siege: The Battle of Hong Kong. Toronto, Doubleday, 1980.

- Lucien Dumais with Hugh Popham, The Man Who Went Back. London, Futura, 1975.

- John Melady, Korea: Canada’s Forgotten War. Toronto, Macmillan, 1983.

- Patricia Giesler, Valour Remembered: Canadians in Korea. Ottawa, Veterans Affairs Canada, 1982.

- John McCrae, In Flanders Fields and Other Poems. Edited by Sir Andrew Macphail, Toronto, Briggs, 1919.

Source: Veteran Affairs Canada