Disaster Does Not Discriminate

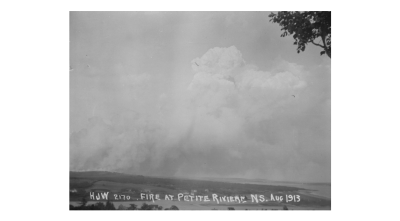

In the summer of 2008, my Aunt drove me from Purcells Cove down Herring Cove Road towards my house, which is just outside Halifax’s city limits. This is the longer way around, but we prefer to drive along the coastline. This is my favourite drive in the world. On one side of the road, the open ocean narrows into the Port of Halifax. You can watch ships come in from the Atlantic on a clear day. On the other side of the road is vast crown-land: dense forest speckled with lakes and woven through with paths and streams. That summer day was different. A fire had just swept through the area, decimating the forests of my childhood and the generations before my family’s arrival. The view from my house, once a comforting front of dense trees, was now clear to the ocean. To this day the forest looks different.

I don’t think about this fire often. I wasn’t home at the time and a fire of its magnitude hasn’t been something that happens regularly in the area. Nova Scotia is the place of hurricanes and tropical storms. Now, working through the Canadian Disaster Database (CDD), it is never far from my mind.

We harvested data from the database based on a single criteria: at least one person was evacuated in each of the disasters we are researching at this stage of the project. Of the 1,119 disasters in the database, we are looking into 344, representing 1,175,789 evacuated people. 1,175,789 people who left their homes, sometimes for months, as disaster struck their communities.

Our master spreadsheet can numerically sort the largest number of people evacuated in a single event to the least. With the click of a button I can pull other numbers just as easily. 2,858 fatalities are recorded in this selection of events. 11,589 injured. Events are included and excluded from the CDD based on numbers and they are included and excluded from our evaluation of the database based on numbers. At times this seems to put the disasters in an abstract category of events that didn’t really happen to any one person, or any one community. They become nameless, placeless events.

I think that’s where the value of our research lies. We are searching for the people and the places that are invisible in the database. Disaster does not discriminate. It is our job at the Disaster Lab to uncover the impact these events had on people in Canada and beyond.

My hope with this project is that the reporting and recording of disasters in Canada focuses on human and environmental impact as inseparable things. We are not even a quarter of the way through our selection of the database and already patterns are emerging. Indigenous communities in Canada are disproportionately affected by environmental disasters and are fighting to be a part of the conversation around mitigating the increasing occurrence of disaster in their territories. Lower income and racialized residents have disproportionate access to disaster relief such as safe and secure temporary housing and post-disaster support. Too often, inquiries into disasters focus on the financial implication for municipal, provincial, and federal governments while ignoring how disasters impact communities in different ways that go beyond numbers.

I think of my family and neighbours leaving their homes amidst the smoke, unsure what they would return to. I imagine the fear, the urgency, and the uncertainty of the disaster as they lived it. This is the reality for thousands of people right now in British Columbia, Haiti, and Afghanistan. It was the reality for the 1,175,789 people recorded in the database. Each one of these people was forced to move from one place to another because of disaster, and disaster, and how Canadian officials define it, affected each one of these people differently.

– MA Candidate, Arden Hody