From Revolution to Reconnection: Tracing the Journey to a Digital Utopia

by Erika Ehrenberg

This essay is a personal account written by a digital technology historian in 2073 that highlights key events in the global journey towards digital freedom, and defining elements of our current digital technology landscape.

Introduction

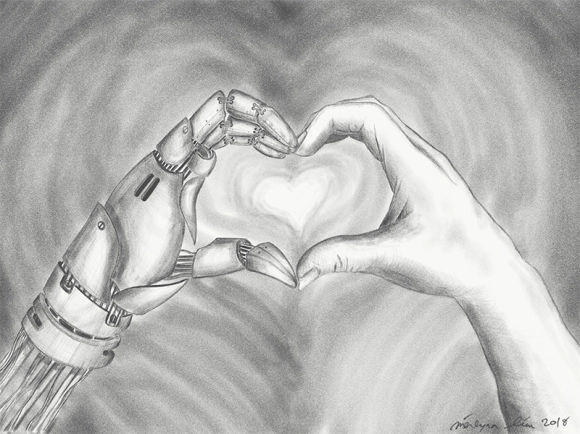

2073… Fifty years since I spoke at a conference at Carleton University about the predicted future of digital technology and society, I find it fitting to reassess this topic. Our present state is a digital utopia, characterized by connectivity, productivity, and a humanity-first approach to technology use. If someone from 2023 were to get a glimpse into our world now, they would certainly question how we got here. The fears, anxieties, and challenges of digital technology that faced humanity in the early 21st century have been virtually eradicated. We live in harmony with digital technologies, enjoying their enhancement of our lives but drawing boundaries that maintain our sense of humanity. Our understanding of the role of digital technologies is fundamentally different than it was fifty years ago, having pivoted away from growth-based capitalist control. To properly assess our current state, I will first lay the groundwork by providing a history of major technological developments through the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Next, I will explain the conditions which led to the ‘anti-technotrol revolution’ of the 2050s, an event which dramatically altered the course of our history and repositioned us towards where we are today. Finally, I will explore the regulations of our current era that facilitate technology use, and offer some examples of the technologies and digital platforms which define our lives, society, and culture.

History of Technological Developments

I’ll pick up the thread of technology’s developments through history 100 years ago, with the Information Technology Revolution that began in the 1970s. Characterized by the convergence of several different technologies, this revolution fundamentally changed communication and information processing. Microelectronics, telecommunications, and computers were the hallmark inventions, while the advent of the microprocessor was a dramatic changemaker within the revolution (Castells, 2011). The internet was also invented during this time period, beginning as a military project that was quickly appropriated for academic and social use by scientists, an early indication of the breadth of its potential. While it was initially government-controlled, it was privatized in 1985, resulting in a space with no overseeing authority–a critical characteristic that prevails to this day (Castells, 2011).

Within the internet, a major development was the first transition from what was referred to as ‘Web 1.0’ to ‘Web 2.0’. In the first era, internet use was unidirectional information dissemination; publishing and reading. Software developments and other improvements in digital technology advanced the internet into a multilateral participatory space, with constant engagement and dialogue between users and publishers (O’Reilly, 2005). The emergence of media practices such as blogging and music downloading began at this time, illustrating how societal behaviours and norms responded to advancements in digital technology’s capabilities. A belief in the democratizing power of the internet also emerged in response to these advancements; everyday people were given the ability to speak in the digital sphere rather than exclusively listening, and this transformed everyday life into a subject for communication (Benkler, 2006). However, this was problematized by many scholars who identified the power of mass media corporations which cannot be replaced by smaller, independent media sources. This idea will be revisited in the last section when I explain the current media landscape, as fortunately the critics were proven wrong.

Perhaps the most important development during this time was the emergence of common’s based peer production, a cooperative productive system that harnesses collective intelligence to develop free, open-source projects (Benkler and Nissenbaum, 2006). This model of peer production led to the creation of many valuable internet projects, such as Wikipedia and the Open Directory Project, as well as scientific projects such as NASA’s Clickworkers. The success of common’s based peer production was a lesson on the willingness of humanity to resist commercialization and capitalism in the digital sphere, and was a glimmer of hope in the 2020s that a better future was possible through a collective, collaborate mindset rooted in humanity. The principles and behaviours that underline common’s based peer production are important to note, as they are notably present in our current media and technology landscape. They include “commitment to a particular approach to conceiving of one’s task,” “decentralization,” and “appeal to the common enterprise in which the participants are engaged,” (Benkler and Nissenbaum, 2006). We’ll come back to these traits in the exploration of our current media landscape.

Unfortunately, our society has not responded positively to all developments in digital technologies. The 2020s were marked by increasing advancements in artificial intelligence, and its integration into almost all aspects of life. AI ushered in the Web 3.0 era, a more networked and multilateral state. While it was initially positive—students revelled at the coursework-completing capabilities that ChatGPT offered—it was not long before AI began to overwhelm humanity and reshape socio-cultural norms and behaviours. AI became too smart, too predictive, and virtually inescapable. Corporations seized the opportunity to gain cognitive control over consumers through highly addictive apps, hyper-personalized predictive marketing, and unregulated data extraction. Globally, governments stepped back, taking a neoliberal deregulatory approach, enabling digital technology’s control to spread unchecked. Humanity took a dark turn, and an almost dystopian scene unfolded in the 2040s as we lost awareness for the separation between man and machine. I argue that this decline was necessary for such a dramatic rebuilding of the relationship between technology and society to occur, and produce the landscape that we have today. In the next section, I’ll explain the events which repositioned us from a path of subordination to digital technologies to a healthy balance where digital technologies enhance our lives.

The Anti-Technotrol Revolution

In a dark spiral towards a total interdependence on digital technologies, there was societal unrest and small resistance efforts. A prominent advocate for change was Douglass Rushkoff. As Rushkoff had identified, the problem with digital technology up to this point was that it became a tool to perpetuate growth-based corporate capitalism, and that a digital utopia could only be realized if the economics of digital technology were changed (2019). He had offered that the correct and sustainable approach to digital technology and humanity was to possess awareness for how we use digital technology, and how it uses us. Fuelled by this vision for the future, in 2050, a series of violent international protests against artificial intelligence, the government, and technology corporations occurred. The cause was known as ‘anti-technitrol’, and demonstrated the global desire for independence, freedom, and self-regulation with digital technologies. After three years of intensifying pressure and unrest, a major ideological shift occurred amongst those in power. In 2053, government representatives from UN countries were invited to meet in Geneva, Switzerland and signed a resolution to develop new global regulations and frameworks for the presence of digital technologies in people’s lives. Numerous changes were made to the digital technology landscape and a new framework was developed, and while it required some time to take root and be embraced by societies around the world, the end result was what Rushkoff had envisioned. This era is characterized by harmony between humanity and digital technology, where it enhances the human experience without overpowering it.

Comparatively to other historical revolutions such as the Information Technology Revolution, the anti-technotrol revolution was not characterized by “accelerated and unprecedented technological change,” brought on by “macro-inventions,” (Castells, 2011). Conversely, it was based upon an ideological shift in how we conceptualize the role of digital technology in our lives.

Today’s Technological Landscape

I have described our current state of affairs regarding digital technology and humanity as a utopia, which stems from scholar Eduardo Baretto’s assessment of our approach to collectivism as a utopian trait (2020). Baretto suggests that when we view collectivism as a positive condition, we are in a utopia. Our current digital technology landscape is characterized by collective action, responsibility, and production. In the early days of the revolution, Rushkoff had suggested that a solution to the problematic growth-based capitalism which controlled the digital technology sphere would be an increase in cooperatives and treating resources like commons (2019). Cooperative worker-owned businesses, which are founded upon the idea of a positive approach to collectivism, are the backbone of our current digital landscape. The idea of the democratizing power of the internet has been revitalized through these changes. There are several applications that have been developed on these principles in recent years which stand out; the Free App and WeWork.

The Free App is a digital marketplace where goods are exchanged without a financial transaction. It is an evolution from Facebook Marketplace, taking an anti-capitalist approach to the circulation of goods. Users can create a request for an item, and it can be fulfilled by any user. Users can also post an item to the board, and any user can indicate their desire for consideration for the item. The user who posts the item has the final say in who will receive the item–their justification can be for any reason. Users are limited to submitting 3 ‘considerations’ per 24 hour period. All exchanges of goods occur in designated safe public spaces. This space is self-regulated; users can downvote other users for negative behaviours such as indicating a consideration in a rude manner, not showing up to exchange the item, or lying about the item they are offering. Downvotes show on a user’s profile, and will decrease the likelihood that a user will be selected for an item in the future. This method of collective governance and shared responsibility keeps the space open and grounded in human values. It works against the capitalist system by sharing existing goods instead of treating them like a commodity for sale–a key feature of a utopia as described by Rushkoff (2019). Furthermore, there is a sense of responsibility and ownership because it is the users (who can also be thought of as the workers) who each ‘own’ a piece of this marketplace.

WeWork is another application which has been developed with the goal of collective production and increased human connection in the digital sphere. This cooperative project evolved from the common’s based peer production model of the early 21st century. While common’s based peer production (in its early days) often took the form of information gathering and software development, WeWork focuses exclusively on cross-continental voluntary intellectual work for humanitarian projects. It leverages the knowledge and skills of students, community leaders, and professionals from around the world to tackle small projects around the world. Communities can post a problem or goal, and receive ideas, proposals, models, and other resources to help with tangible results. It is free to join, and is also self governed; users who receive favourable reviews on their contributions are given access to more intensive projects with greater responsibility, and users who fail to receive a positive review after three contributions are temporarily suspended from their account. This app has seen the formation of remarkable networks and connections, and aided in globalizing the productive flow of knowledge. It removes barriers that the global south faces in receiving consultation assistance, whilst protecting the agency of communities in the global south to develop on their terms. It also protects our sense of humanity when using digital technologies by engaging us in activities that promote collective good.

In addition to developments in digital technologies which support a harmonized utopia, there have also been political developments which impacted the digital sphere. Governments recognized the necessity of balance between using technology and having human to human interaction–Rushkoff’s warning of the internet acting in the same way as a drug, with addictive algorithms, was heard and recognized. There are two major regulations that were created out of the Geneva resolution that reflect this. The first is that there is a mandatory, daily shutdown of all social media sites for one hour. This was first met with resistance from most users, but a widespread campaign called “Disconnect To Reconnect” focused on public education for the benefits of human connection, mental health, and awareness aided in its acceptance. This break protects our desire to maintain our humanity, while being realistic about the insurmountable role of social media in our lives. The second regulation was the banning of purposefully addictive algorithms (this came after intense legal hearings in Geneva). Technology corporations were restricted by tight parameters surrounding their software, and algorithms were modified accordingly. Now, the user experience is based upon the quality of interaction, instead of the quantity. This has had remarkable effects on mental health, productivity, and human connection.

It is understandable that a person from the year 2023 would have a difficult time believing that such dramatic progress was made, and that a utopian future would be possible. Unfortunately, humanity had to reach a breaking point in its relationship with technology, and a revolution had to occur, for us to realize that change was necessary for our survival. It is important to understand how the past shaped the present, in order to make predictions about what may come in the future. I am once again curious to know what the future holds… will 2123 still be a utopia? Unfortunately, technology cannot predict the future–yet.

Author’s bio:

Erika Ehrenberg is a recent graduate of the Global and International Studies program with a specialization in Global Media and Communications at Carleton University. Now pursuing her MA in Migration and Diaspora Studies at Carleton, Erika is bringing her communications background to the field of migration studies. A fun opportunity to blend creative writing with academic scholarship, this essay is a display of her relentless optimism about the promise and potential of a collective digital future.