Techno-Tyranny: When the Future Became Our Prison

by Jake Andrews

Introduction – My Dystopian World

I chose to write about a dystopian future where technology has doomed society. I will write in the first person as if I was living in this future myself. Starting from a surface level, I will detail from a broad perspective what this world has become in 2073. From there, I will peel back the curtain to unveil how it got to that point and highlight the moments that defined the beginning of the end for this doomed civilization. Finally, I will discuss a hypothetical scenario that shows how these citizens might claw their way back from the brink of annihilation and reclaim their society.

The Dark Present

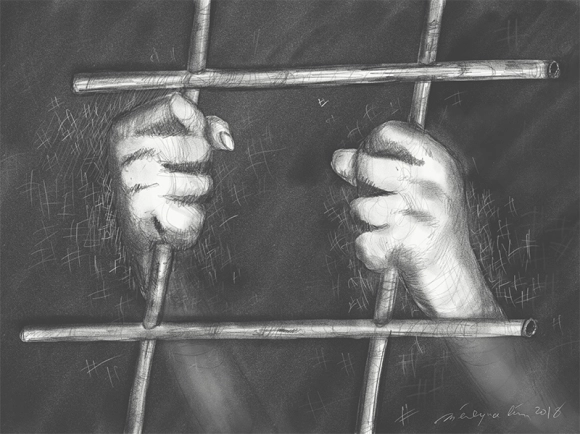

The year is 2073. Humanity is a shadow of what it once was. War has taken its toll. Hope and optimism have given way to tyranny and desolation. The natural world is a wasteland; climate change has accelerated, and high-tech weaponry has ravaged the landscape. All our food is artificial, and pollution has desecrated the air, land and sea globally. Those who held out through the wars eventually gave up control over our lives to the government in hopes they could fix this worsening mess. They sold us to the highest bidder. When the truth revealed itself, that those who sought to save us really meant to enslave us, we had the opportunity to fight, many chose to kneel.

We had the opportunity to stop the sobering wheel of technological progress, but we chose to blindly stumble into the fire. Now, all that remains is this bleak, miserable existence. The internet, robotics, and artificial intelligence were supposed to be our salvation. They became the hammer, and we became the nail. The mice have accepted the wheel, and on and on we go, running towards destruction. How did we get here?

Where Did It All Go Wrong?

The beginning of the end came in 2035. However, the events that led to that point came much sooner. Nobody knew it at the time, but the invention of the internet started us down the path to our own doom. The cultural lag that accompanied it meant we did not feel the real ramifications of what we had created until much further down the line. Industry responded to its introduction, governments attempted to regulate it. They largely failed – their attempts were criticized, and the lag they created caused humanity to ultimately suffer as social philosophies could not adjust. Government attempts to discuss regulation were labelled as a mix of “satanic and angelic images that have surrounded, justified, and denigrated technology without realistically assessing its actual capabilities and limitations” (Fisher & Wright, 2001). Regulation never came. Those ominous capabilities would eventually become crystal clear, and the limitations of humanity would accentuate the darker side of this new technology.

A lack of regulation in the 2000-2030 period meant the internet became the digital wild west. We were taught that, “a society that provides opportunities for virtuous behavior is one that is more conducive to virtuous individuals” (Benkler & Nissenbaum, 2006, p. 394). Open-source collaboration, cooperative business models where workers became owners, and free and readily available information and software suggested a digital paradise. Our trusting nature got the better of us. A few bad apples in this utopian system led to the “Copenhagen incident”.

A group of Danish students at the University of Copenhagen created an open-source software protocol to bypass government security systems. It became a haven for hackers and enemies of the Western world. One thing led to another, and the group launched missiles of the US military at strategic military installations and government buildings in retaliation to the never-ending US occupation of the Middle East and other parts of the world. This unprecedented attack led to a manhunt for those responsible; they were swiftly apprehended, and their discovery led to the shutdown of the open-source software program, prosecution of those involved, widespread paranoia and war between nations, increased scrutiny on open-sourced platforms and the internet in general, and led to the type of regulation we tried so hard to avoid when the technology was first introduced. Copenhagen became ground zero and was reduced to rubble. The US government lashed out at the entire world. Other nations fought back and were met with nuclear weapons and deprivation of vital resources. Only direct allies of America, the wealthy, and the connected remained afterward. The world was reduced to an arid wasteland, and nobody sought to fix it when the bombs stopped. We simply left the countries that lost the war to rot – the “winning side” began to think about an easier way. As the natural world and our resources dwindled, the governments of the world became ill-equipped to deal with the growing problem at hand. In 2035, we began the age of Techno-dystopia. Technology was the answer to everything – food, pollution, production, industry, entertainment, law and order. Now, most of the population are mindless, stuck in a zombie-like state, giving their all to the machine.

Humanity has become too accustomed to our addiction to technology. When the internet was first invented, “people did not equate technology to the use of a drug; they thought more about how the installation of technologies would affect their computer or device rather than how use of these technologies would affect their lives and mental state” (David Pakman Show, 2019, 5:57 – 6:53), now we have truly come full circle where we have no life without it. Technology has rendered us in a trance-like state using addictive algorithms fostered in studies of captology. Humanity did not understand the dehumanizing compromises we needed to make in order to interact with technology in a better way and compensate for it (Pakman, 2019).

AI development and robotics began to be employed on a mass scale to clean up the mess humans had made. The internet and wearable devices became a way to monitor, track, and account for the growing slave population needed to facilitate the new reality. Oppression, control, and regulation of the people by the ruling elite became the norm. We lost all sense of individuality and became a collectivist society. Our news lost all meaning; fake news proliferated, and the fabrication of real news through propaganda made discerning truth from lies almost impossible. Egalitarianism and any sense of social justice became a distant memory.

The day they locked our devices was a day I will never forget. Such a coordinated effort. Like a super villain out of a movie, these corporate overlords flipped the switch of ultimate subjugation. In an ironic sense, we should have seen it coming. Art imitates life—1984, Terminator, Ready Player One. Did we refuse to believe the possibilities out of sheer ignorance? How blind we were. Maybe we deserve what we have begotten.

Where Do We Go From Here?

How do we reverse this terrible course of events? How do we wrestle control back from the techno-empowered masters? We have to create a plan. We need to break free from the hold of technology and return to our roots: recultivate the landscape, create farmable spaces, recruit the many to combat the privileged few, and find a way to scramble the machines. At first, those in political agreement with the corporations benefited, but now, even those people see the error of their choices. Very few actually prosper in this new world, so we need to remind them of it and recruit more people to the cause. We need the machines to be unplugged for technology to once again become an enabler of prosperity, not a tool for corporate greed and mass imprisonment.

The fact that we are still here shows that it is not the end. The common people are still alive; we are just fragmented and have lost sight of the way to salvation. Rumors of a settlement for the resistance are abound; a hidden outpost exists somewhere and its whereabouts are circulating through cryptic and encoded messages passed around on pieces of paper, a scarce item these days. I was approached in a local bar by a group led by an older gentleman who whispered the words “simul autem resurgemus” into my ear and handed me a message. Hope springs eternal. I have spent the last six months deciphering its meaning. It points to a location in the European wasteland left over from the war. It speaks of a gathering. Talking about it in plain terms is impossible under the watchful eyes and ears of this surveillance state. You have to move into the shadows, out of sight, out of range of their devices in order to see, hear and speak in the language of freedom. I will find my way there, make meaning of it all, rediscover my purpose, and make a difference once again. For me, there is no other option, for this life is truly no life at all.

Conclusion – What Does it All Mean?

“Technology is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral. It is indeed a force, probably more than ever under the current technological paradigm, that penetrates the core of life and mind. But its actual deployment in the realm of conscious social action, and the complex matrix of interaction between the technological forces unleashed by our species, and the species itself, are matters of inquiry rather than of fate” (Castells, 2011, p. 76). The future is in our hands.

I have painted a picture of a dystopian world. In order to prevent our future from becoming like this dystopia, we should pay special attention to our relationship with technology and those who develop the hardware, software, platforms and applications we use and incorporate into our daily lives. Barreto states, “The idea of utopia begins on an island and ends in the future. It goes from where to when utopia changed from a better world elsewhere, out there, to a better world in the future. Yet, as it continues into dystopian fiction those ideals are reserved, now it is not a better world in the future, but a worse one. They are both about hope: one tells you a better world is coming, the other tells you there is a terrible world in the future, but if you recognize these elements, then we can stop it now” (Barreto, 2020, 17:18-17:53). Let us hope our future generations recognize these elements if they begin to encroach into our reality if they have not already.

References

Benkler, Y., & Nissenbaum, H. (2006). Commons-based Peer Production and Virtue. Journal of Political Philosophy, 14(4), 394–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2006.00235.x

Castells, M. (2011). The Information Technology Revolution. The rise of the network society.

David Pakman Show. (2019, May 10). Is Our Technology Future Utopian or Dystopian [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZGPdkP4gdgs

Eduardo Barreto. (2020. April 24). Lecture 3: Utopias and Dystopias [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4BC95DGEYc&t=1075s

Fisher, D. R., & Wright, L. M. (2001). On Utopias and Dystopias: Toward an Understanding of the Discourse Surrounding the Internet, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 6 (2), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00115.x

Author’s bio:

Jake Andrews is a recent graduate of the Carleton Communication and Media Studies program with a passion for writing, music, travelling and board games.

Jake is a fan of dystopian literature and entertainment. Drawing inspiration from Terminator 2, 1984, Mad Max and other famous pieces of fiction, he created this story of a world in despair, of a future that may yet come to be where the desperate few cling to hope that they can reclaim what they lost in a world ruled by technology, and militant corporate greed.