Chinese writing differs significantly from what we English speakers are used to, that much is no secret. How it got its start, and the underlying logic that drives millions of people to learn this written language is, on the other hand, something you may not know, and it’s exactly what today’s blog post is going to look at.

Chinese writing differs significantly from what we English speakers are used to, that much is no secret. How it got its start, and the underlying logic that drives millions of people to learn this written language is, on the other hand, something you may not know, and it’s exactly what today’s blog post is going to look at.

Familiarizing yourself with the basic principles of Chinese characters doesn’t just improve your Chinese reading and writing, but if you’re a bit of a historical linguistics nerd (like myself), then it’s a boatload of fun too!

Writing systems are generally divided into six types: logosyllabaries, which represent sounds and meanings; syllabaries, in which each character represents a syllable; abjads, where every character is a consonant; alphabets, where each character is a consonant or vowel; abugidas, wherein characters stand for “a consonant accompanied by a particular vowel,” with any other vowels indicated by additional symbols (diacritics) added to the consonantal characters; and finally, featural scripts (of which you’re most likely to be familiar with Korean), in which the shapes of characters encode information about the phonetic properties of the sounds they represent.1

| Type of Writing System | Example |

| Logosyllabary | 包撲冞匪 (Chinese, Simplified)2 |

| Syllabary | あいうえおかきくけこ (Japanese, Hiragana)3 |

| Alphabet | ABCDEFG (Latin alphabet) |

| Abjad | ابتثجحخ (Arabic)4 |

| Abugida | अआइईउऊऋ (Sanskrit, Devanagari Script)5 |

| Featural Script | ㄱㄲㄴㄷㄸㄹㅁㅂㅃㅅㅆㅇ (Korean, Hangul)6 |

Written Chinese is one of these logosyllabaries, combining sound and meaning into one, and can be traced back to 1400 BCE.7 In the time since, they’ve undergone some significant changes – not in their underlying system, but certainly in their form.8

Wang (1973) reproduced in Handbook, p. 557

There is one minor complication with this simple story, and that is the fact that speakers of different regional languages often invented their own scripts. The Xixia, Bai, Zhuang, Miao, and Yao people, for instance, all had their own writing systems (albeit of differing complexities).9

I will be focusing on the evolution of Chinese characters (or 汉字, Hànzì) as we know them today, since it is the most studied of these writing systems.

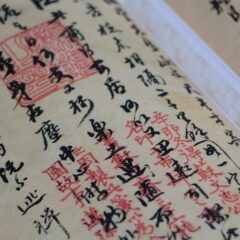

As you can see, the Chinese characters we know and love today barely resemble the original symbols they developed out of. Over time people have also brought a great number of calligraphic fonts –some more legible than others– into the mix, which leads to a truly diverse wealth of ways in which you can write Chinese.

Originally, written Chinese was accessible only to nobility, as its register is very different from any variety of spoken Chinese.10 In its earliest form, writing was used primarily for divination and record keeping, and was carved on bamboo and animal bones, leading to a distinctive shape.11 During the later Shang Dynasty, carvings on bronze were used in formal occasions.12

As time passed, scripts diverged and became more diverse, and in about 221 BCE, the first Chinese emperor, Qinshihuang, declared the ‘small seal script’ (小篆, Xiǎozhuàn) the official writing system of China.13 For reasons of ease and speed of writing, these characters were more abstracted compared to the early picture-like symbols, characters were made more symmetrical, and strokes were simplified.14

It wasn’t until the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589 CE) that the so-called ‘regular script’ (楷书, Kǎishū) overtook the small seal script in prominence.15

The next major development in Chinese writing was the 20th century Chinese Characters Simplification Scheme. The government scheme was aimed at improving literacy by simplifying the writing system, and got rid of about 1000 characters, replacing these with simpler variants.16

That’s why nowadays you’ll be faced with the challenge of choosing between learning ‘simplified’ or ‘traditional’ Chinese characters, the former of which is used in Mainland China, and the latter of which is prominent in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.

But don’t worry, the vast majority of characters remain the same between the simplified and traditional scripts, so learning both variants isn’t a big hurdle to get over!

Despite the fact that I’ve been calling Hanzi ‘Chinese characters’, China certainly isn’t the only place they’ve made an impact.

Chinese characters were brought to Korea as early as 403 BCE, as well as Vietnam, and Japan.17 For a long time, Korean nobility used Chinese characters to write, until 1486 when they were replaced with the Korean featural script called Hangul.18 Nowadays, Chinese characters can be found at historical sites in Korea and are used (rarely) in certain official or formal contexts.19

Vietnam has adopted its own writing system by now, but relied on Chinese characters as its only official script for over a thousand years, from the 1st to 13th centuries.20

In Japan, meanwhile, a large number of Chinese characters were borrowed and are still used in its writing.21 Japanese uses Kanji (derived from Chinese characters) as content words, Hiragana “for writing grammatical morphemes attached to Chinese characters”, and katakana for loan words.22

How is it that written Chinese has been used across such diverse language varieties –both within and without China–, and has remained so stable over time? To answer this question, we have to turn to the basic structure of Chinese characters.

Chinese characters are what we call ‘morphosyllabic’. Each character represents exactly one syllable worth of speech sounds, and corresponds to one morpheme (minimal unit of meaning).23

Each individual stroke that makes up a Chinese character is meaningless, and doesn’t give you any information about sound. But, Characters can be broken up into sub-components called ‘radicals’.

These radical are further subdivided into two main types: phonetic and semantic.24 As their names suggest, phonetic radicals tell you about the sound of a character, and semantic ones tell you about its meaning.

For example, the character 晴 (qíng, ‘clear/sunny weather’) is composed of the radical 日 on the left side (rì, ‘sun’), and 青 (qīng, ‘blue/green/black’ –confusing, I know–). Obviously, the left-side radical is semantic in nature, and the right-side radical is phonetic.

There is one minor (read: major) caveat to this system, and that’s the fact that phonetic radicals are notoriously unreliable.

Not only is it impossible to know the tone of a word from its phonetic radical (if you didn’t know already, Chinese languages are tonal), but it is rare to find a radical that consistently maps to one syllable.

Usually, only part of the syllable will be indicated by the phonetic radical, and sometimes none of the sounds match!

To add to this, a great many Chinese characters have multiple pronunciations, used in different contexts and to convey different meanings.

So, Chinese characters are primarily meant to encode semantic information. This makes sense, since (Mandarin) Chinese has a lot of homophones –words that sound the same but mean different things– so having the meaning of a word represented by a character, rather than the sound, helps readers distinguish between homophonous words.

What this combination of phonetics and semantics allows, too, is that you can read written Chinese across a range of different regional varieties, all of which differ in their pronunciation!

If any given character is “not directly related to speech sounds,” then it can be adapted to the pronunciation of different dialects and even different languages, without (significantly) affecting its meaning!25

For those of you who are familiar with the IPA,日 has been variably pronounced [njit] (Old Chinese), [nyit] (Middle Chinese), [ʐʅ51] (Mandarin), and [jaat3] (Cantonese), but has retained the same basic meaning of ‘sun’ over time and space.26

So, despite adding to the difficulty of learning to read and write Chinese, the morphosyllabic nature of Chinese characters has given them their impressive longevity!

So there you have it, the history of Chinese characters… albeit incredibly simplified! Language change is a wonderful and fascinating area of study, and that doesn’t just have to include written language. But, there’s no denying that having a strong grasp of a language’s writing system is immensely helpful in your language learning journey. Happy reading and writing!

Reminders

Linguavision’s 10th anniversary is approaching! Come join us on April 9th from 7-10pm in the Kailash Mital Theatre. Entry is FREE!

Follow us on Instagram and Facebook

References

1 Daniels, P. T. (2001). Writing Systems. In M. Aronoff & J. Rees-Miller (Eds.), The Handbook of Linguistics (pp. 43–80). Blackwell Publishers. 44–45.

2 Wikipedia. (2025, February 10). Bopomofo. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bopomofo

3 Wikipedia. (2025, February 13). Hiragana. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiragana

4 Wikipedia. (2025, February 23). Arabic alphabet. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_alphabet

5 Wikipedia. (2025, January 20). International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Alphabet_of_Sanskrit_Transliteration

6 Wikipedia. (2025, February 24). Hangul. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hangul

7 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 554.

8 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 558.

9 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 554.

10 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 556–558.

11 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 556.

12 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 556.

13 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 556.

14 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 556.

15 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 556.

16 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 558.

17 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 554-55.

18 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 554-555.

19 Kim, K. (2024, July 31). Understanding Korean Hanja. Busuu. https://www.busuu.com/en/korean/hanja.

20 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 555.

21 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 555.

22 Daniels, P. T. (2001). Writing Systems. In M. Aronoff & J. Rees-Miller (Eds.), The Handbook of Linguistics (pp. 43–80). Blackwell Publishers. 51.

23 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 555.

24 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 555.

25 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 559.

26 Wang, F., & Tsai, Y. (2015). Chinese Writing and Literacy. In W. S-Y. Wang & C. Sun (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (pp. 554–564). Oxford University Press. 559.