Mind The Gap

Nobel Prize Winner Gerhard Herzberg, Carleton’s Former Chancellor, on Scientific vs. Humanistic Thinking

Most scientists have found in their non-scientist friends a lack of understanding of even the most elementary concepts of scientific thought and I am sure humanists have had a corresponding experience in their relations with scientists. This “gulf of mutual incomprehension” is clearly understandable since both the scientist and the humanist pursue their studies with the same aim of achieving a better understanding of man and his world — the scientist by his efforts to interpret the physical world and the humanist by creative works that try to understand the human mind.

There is, of course, a fundamental difference between scientific and humanistic knowledge. This difference becomes particularly apparent when we look at the relations of each group to the masters of the past. To understand mechanics or astronomy it is not necessary to read Newton in the original; to understand present-day nuclear physics it is not necessary to read the original papers of Rutherford, one of its great pioneers.

Once a scientific discovery has been made it ceases to be personal to the discoverer and becomes part of the university body of scientific knowledge. Except for historical reasons, the original papers are quickly superseded by superior accounts that are rapidly provided by teaching experience and didactic skills. But the writings of a great critic or historian — and even more those of poets and other artistic creators — are part of their own message and to paraphrase the argument would be to destroy the effect.

Knowledge and insight here are private and personal and the message can be obtained only by constant reference to the original work. In spite of this fundamental difference in their attitude to the past there is no intrinsic reason why a scientist should not have some knowledge and appreciation of art, literature and music, or why a humanist (or lawyer or politician) should not have some knowledge and appreciation of science and mathematics.

The lack of understanding between scientists and non-scientists is positively dangerous at a time when the applications of science determine more and more of our lives, when indeed the survival of the human race is dependent on our ability to apply our scientific knowledge to overcome the undesirable effects of technology and to remove the great disparity in standard of living between the developed and developing countries.

From Gerhard Herzberg’s installation speech when he became Carleton’s chancellor in November 1973, published in The Value of Science in Society and Culture: Selections from the Speeches, Essays and Articles of G. Herzberg (Queen’s University School of Policy Studies, 2019), edited by Agnes Herzberg and Paul Dufour.

Rage Against Injustice

Fatima Meer was one of the most prominent, and yet most under-recognized, voices in South African academia in the twentieth century. She epitomized the public sociologist, described by Michael Burawoy as one who “brings sociology into conversation with publics, understood as people who are themselves in conversation.”

She was driven by an activist sociology for a common society, by a rage against injustice and by a profound belief in the value and capacity of research to convince the powerful of the consequences of their choices. An intense humanism overlay all of her writing. Ideas about human freedom, equality, sociability and progress run through her work.

In numerous books and essays, she offers a set of ideas that ran counter to those of the colonial and apartheid state, and at times counter to the theories of other engaged scholars on the left. Where her colleagues foregrounded, and indeed privileged, class in their analysis, she focused on uncovering the life experiences of subaltern groups in ways that understood human life as a complex encounter between structure and agency. This led her to consider race as determinant of life chances, and as a form of power to be exposed in every manifestation.

From Fatima Meer: A Free Mind (HSRC Press, 2019), by Shireen Hassim, the Canada 150 Research Chair in Gender and African Politics at Carleton.

Neurons Firing

Imagine a jar of peanut butter. When you do this, you’re creating, in your mind, something that doesn’t exist — even if you’re imagining the jar you actually have in your cupboard, you’re creating something new. There’s the actual jar of peanut butter, and then there is a separate thing in your mind: a representation of the jar, here and now, not where and when the physical thing actually is.

The actual jar of peanut butter is made of plastic and peanut butter. The thing in your head, the “imagining,” is some pattern of neurons firing in your brain. Even when you use your imagination to remember something that actually happened to you, you’re creating a simulation of a time and place that no longer exists.

This is the essence of imagination: the creation of ideas in your head, composed from ideas, beliefs, and memories. Often, they are not simple ideas, but complex structures. The most spectacular use of imagination is in creativity, but this book isn’t about creativity, which requires the generation of something new and effective in some way.

Acts of imagination need not be new or useful. Imagination also has great uses in more mundane tasks we do every day, such as planning the day. When you think of what route you want to use to get home, or you go through the logistics of where to park your bike, or figure out what order you should run your errands in, you’re thinking of possible realities that do not yet exist.

From Imagination: Understanding Our Mind’s Greatest Power (Pegasus Books, 2019), by Jim Davies, a professor in Carleton’s Institute of Cognitive Science.

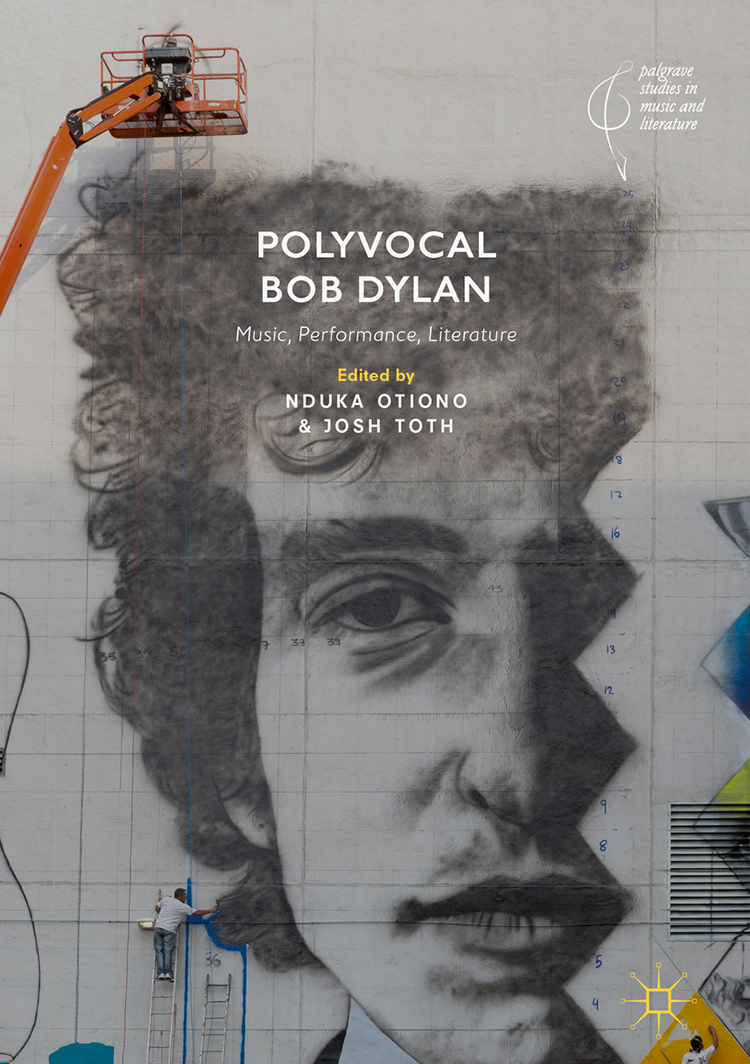

Dylan In Lagos

Although I do not recollect the exact date I encountered Bob Dylan’s work in Lagos, Nigeria’s densely populated commercial and cultural capital city, I remember the circumstances that brought the inimitable artist into my consciousness. I had graduated from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria’s premier university, and had moved to Lagos to pursue a career in journalism and creative writing.

It was in the early 1990s and Lagos — like other cities that serve as cultural hubs (such as New York, San Francisco, Paris, Dublin, and London) — was the dream site for young people determined to “make it big” in life….

Like Dylan’s New York, Lagos was the metropolitan beast where artists armed only with their talents and dreams struggled to find the muse and direction in life. It was not difficult, therefore, to see why Dylan cast a spell on our small Lagos group.

Besides Dylan’s artistic ingenuity and counter- cultural disposition, our group was drawn to artists whose rebellious and anti-establishment personae advertised the kind of fierce creative temperament that we aspired to possess. Nigeria in the late 1980s and 1990s writhed in the death pangs of military dictatorship and a torturous process of transition to democratic governance.

Writers, journalists, activists were jailed for their work. The writer and environmental rights activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa, was gruesomely executed by hanging within this period. So, more than ever before, writers found therapy in their art, while some sought escape through liquor or fled into exile.

From Polyvocal Bob Dylan: Music, Performance, Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), edited by Nduka Otiono — a professor in Carleton’s Institute of African Studies — and Josh Toth.

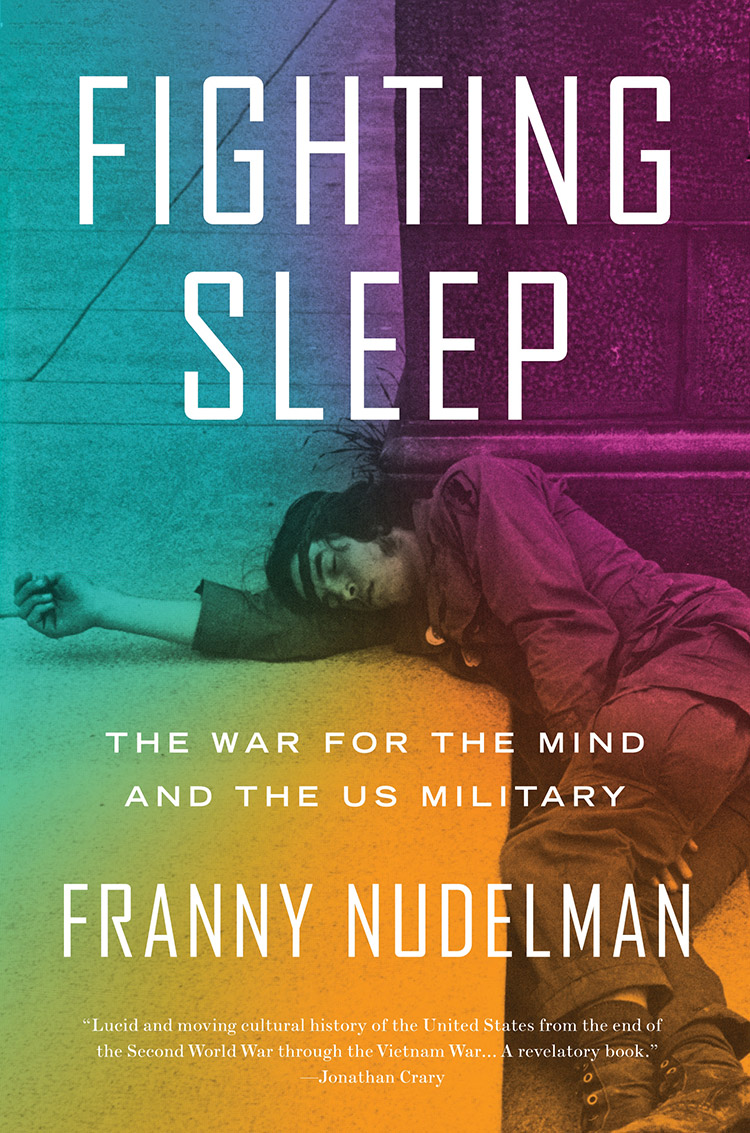

Sleeping Problems

In the spring of 1971, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) fought the courts for the right to sleep on the National Mall as part of their weeklong demonstration, Dewey Canyon III. When the courts denied their petition, veterans decided to break the law by sleeping anyway.

Turning good rest into a form of dissent, hundreds of veterans fell asleep, wondering whether or not they would be arrested by daybreak. Clearly, sleep played a part in the movement to stop the U.S. war in Vietnam.

Still, I wondered, why did the government see fit to let veterans stay overnight on the Mall — singing, talking, even lying down — while refusing to let them fall asleep there? Why did veterans decide to sleep and risk arrest?

This book began as my effort to understand what was at stake in this contest, and, from there, my story grew, traversing the fields of military and mainstream psychiatry, popular and institutional film, documentary sound technology, methods of brain warfare, and the tactics of postwar social movements to arrive back at the scene of soldiers sleeping soundly in the public square.

The VVAW sleep-in speaks powerfully in no small part because it flies in the face of a clinical and cultural record of war trauma that is rife with scenes of troubled sleep: the sleepless soldier and the insomniac veteran are protagonists of an evolving narrative of trauma and its aftermath that spans the course of the twentieth century.

From Fighting Sleep: The War for the Mind and the U.S. Military (Verso, 2019), by Franny Nudelman, a professor in Carleton’s Department of English Language and Literature.

Thursday, January 9, 2020 in Short Reads

Share: Twitter, Facebook