Helping the capital’s most vulnerable residents. Pushing for health equity and safe cycling infrastructure. Funding critical scientific and medical research. Protecting wildlife from people. Breathing life into historic sites. Teaching seniors how to use technology. Getting new tools into hospitals now. Sharing culture. Using data to drive policy change. Empowering Indigenous children and families.

The myriad impacts of COVID-19 have demanded a wide range of responses. Thankfully, the Carleton community is not a homogenous group, and the ways in which students, faculty, staff and alumni have used their education and experience to address the devastating virus and its successive shock waves vary tremendously. In the following package, you’ll read about a diverse and dynamic group of people whose work show how much is possible when we put our collective energy toward alleviating the biggest public health crisis in a century.

- Last Refuge: Helping People Who Have Nowhere Else to Turn

- Uphill Battle: Toronto City Councillor Fights for Health Equity — and Bike Lanes

- Existential Threat: Investing in Technology to Solve Hard Problems

- Nature Finds a Way: Does Wildlife Rebound When We Stay Home?

- History From Home: Digital Heritage Conservation Doesn’t Stop

- Tech Support for Seniors: Carleton Grads See Digital Literacy as a Human Right

- Homegrown Help: Getting New Technologies Into Ontario Hospitals Now

- Cross-Country Checkup: Co-Op Student Joins the Collaborative Health Care Innovation Secretariat

- Virtual Community Hub: The Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre Leapfrogs Into the Future

- Cultural Healing: How a Social Work Practicum Helped Me Find My Niche

Social Work undergraduate student Nicole McLean

1. Last Refuge

Helping People Who Have Nowhere Else to Turn

When COVID-19 upended life in Ottawa, the city’s most vulnerable residents faced heightened risks. Rather than dodge the challenge, Nicole McLean dove in. A rule change allowed the social work undergraduate — a casual employee at Ottawa’s Shepherds of Good Hope homeless support agency — to do her on-the-job practicum at her workplace. McLean talked to Raven in July after finishing an overnight shift at the Shepherds shelter in the ByWard Market and has now been hired on as a case manager.

Our emergency shelter clients come from the streets or the hospital or they’re brought by the police or OC Transpo — people who just need a place to stay for the night. You show them to their beds and watch out over everybody. You’re always moving and basically help clients with whatever they need.

Sometimes there are fights, which our security staff deal with, and sometimes there are overdoses and you’re the first person on the scene. We spray everybody’s hands with sanitizer when they come in and ask them to wear masks, and we try to keep everybody a safe distance from each other.

Among the population we work with, people often have coughs or feel sick — these aren’t new symptoms, it’s just their day-to-day lives. Everybody was told to stay at home when the pandemic started, but home wasn’t an option for them.

Sure, there are risks, but because we’re following proper safety procedures I’m not concerned about my own health. For a while, I wasn’t seeing my family, which gave me a new perspective, because a lot of our clients aren’t in contact with their families. Working at the shelter, I’ve come to see that we’re all one big community and we need to support one another. The pandemic doesn’t change that.

My initial contact with the homeless population was when I started at the Shepherds of Good Hope about a year and a half ago, and I fell in love with it. Every day is different and you never know what to expect or who you’re going to come in contact with, but you meet people and build rapport with them.

One night when I was working, a woman who had been sexually assaulted came in. She’s hearing impaired and was worried that she wouldn’t be able to tell anybody what had happened. I’m learning American Sign Language and happened to be on shift, so I could translate for her. I sat in a room with her and a police officer and helped her make a report. She came back the following weekend and felt safe and comfortable, even though the assault had taken place nearby. She remembers me, and seeing her around every so often warms my heart.

Joe Cressy (right) with fellow city councilor Mike Layton on a new bike lane on Toronto’s University Avenue/Photograph by Joan Wilson

2. Uphill Battle

Toronto City Councillor Fights for Health Equity — and Bike Lanes

Since first getting elected in 2014, Toronto city councillor Joe Cressy — a Bachelor of Public Affairs and Policy Management graduate from Carleton — has represented the downtown ward of Spadina-Fort York, championing affordable housing, expanded community services and safe cycling infrastructure. The latter has received a lot of press over the past few months as thousands of people took to two wheels for transportation and recreation. That work, and Cressy’s role as chair of Toronto’s Board of Health, has put him at the forefront of the city’s pandemic response.

With COVID-19, whether you’re a decision-maker or a front-line worker, it’s been like running up a down-bound escalator for months — you can’t stop or you will fall, so you just have to keep sprinting.

The pandemic has exposed many things, including the systemic underfunding of public health infrastructure. COVID-19 has been most fatal for people who are experiencing inequities such as inadequate housing or precarious employment. The social determinants of health — income, housing status, race and so forth — are more likely than anything else going to dictate who gets sick, who lives and who dies.

In the world of public health, we have been rolling this rock up the hill for years. The difference now is that some people are listening.

Could this be a transformational moment that we emerge from stronger and more resilient and finally address these vulnerabilities? It could, but I am not entirely sure. I think we might see some incremental improvements when more drastic change is required. I believe that coming out of this we will continue to roll that rock up the hill.

Going back to March, it was always a conversation of when not if Toronto would increase space to facilitate safe transportation options. At the time, the predominant advice was to stay home, but we knew that as things opened up, we would need to support active transportation, at which point the when kicked in — the need for an interconnected cycling and pedestrian network. More broadly, we know that we need to redesign our streets to move people safely.

That’s a 21st century objective for cities like Toronto separate and apart from COVID, whether it’s weekend closures of major streets or the establishment of 40 additional kilometres of cycling lanes to facilitate mobility for people who are travelling to and from work.

Going into Carleton, I had mostly been involved in community issues and protests, so the education I received around how policy change can take shape inside legislatures and the public service was very helpful. It was an exceptionally rich environment in terms of learning how to build coalitions and approach change.

In the context of Toronto city council, I’d be lying if I told you that suddenly there was a newfound consensus that cycling infrastructure is an overarching priority. Rather, I believe there was a consensus reached in the urgency of this moment.

I describe the art of changing the City of Toronto as radical incrementalism. Sometimes it can be slower than you want to go, but you’re ultimately heading in the right direction.

Thistledown Foundation founders Fiona McKean and Tobi Lütke

3. Existential Threat

Investing in Technology to Solve Hard Problems

When Fiona McKean and Tobi Lütke launched the Thistledown Foundation in January, the couple seeded their charity with a $150-million endowment and focused on carbon removal technologies. McKean, who runs The Opinicon Dining and Resort southwest of Ottawa and has a master’s degree from Carleton’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, and Lütke, the founder and CEO of Shopify, want to support climate change solutions through philanthropy. Then the pandemic hit and Thistledown set its sights on improving supply chains for personal protective equipment and accelerating COVID-19 research, the latter through a $5-million contribution to an organization called Fast Grants.

In January, I was with three people in Thistledown’s temporary office — an abandoned Italian restaurant in Ottawa that smelled like sour beer — talking about carbon. Then, in March, a huge shift took place. It was a surreal moment that felt like we were suspended in time and nobody knew what was on the other side. We faced an existential threat. So we started talking to doctors and scientists we knew. We read research papers and data sets. It was terrifying and intense, and we didn’t have enough info to know what to do. Then Fast Grants came to our attention. It’s an American project with a panel of biomedical scientists who make funding recommendations, and we sort of shoved a wedge under the door so we could support Canadian research.

Clearly, right now we need doctors, we need epidemiologists and we need biologists, and we need their research, but from a donor’s perspective, I can’t vet them. How do you gauge the veracity of all the claims you’re bombarded with? You turn to the experts. Even though everybody was busy and scrambling, Fast Grants funded more than 130 projects within 48 hours of the first call for applications in April and responded to the second round of applicants in July within two weeks.

Canada has a long history of quietly putting our elbows up to make sure that we have a seat at the table. If we’re not included, then the solutions do not have our particular problems in mind. Every country is having a different experience during the pandemic, and even though we’re all dealing with the same virus, every country’s toolkit is different.

One example of somebody we supported is Dr. John Bell, a cancer researcher at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. He immediately switched gears to see if the work that his lab was doing could be applied to COVID. [Dr. Bell’s research is “trying to create multiple vaccines … delivering coronavirus proteins directly to the critical cells required to generate an effective immune response.”]

The connection between climate change and COVID is at the species level. Thistledown believes that technology can help address hard problems. The question was never if we could try to help during the pandemic, but how — how can we go beyond sprinkling money around with little impact? I think people shy away from philanthropy because of that, but we took a leap. We found the right people to support, and now we’re leaving them alone to do their work.

A road-killed hummingbird, one of the bird species monitored by the C19-Wild Research Group/Photograph by Ewen Ebarhardt

4. Nature Finds a Way

Does Wildlife Rebound When We Stay Home?

By Susan Nerberg

Last spring, with airplanes grounded, cars and trucks parked and people isolating at home, there were reports of wild turkeys, deer and even cougars exploring city cores. Lenore Fahrig knows how rare this is.

For the past 30 years, the Carleton biology professor has been studying the fallout from people getting in the way of animals. So when the C19-Wild Research Group was formed to find out what happens when we get out of their way, Fahrig was asked to serve on the advisory panel, drawing from her decades of research into the effect of roads on wildlife, including birds.

Biology Prof. Lenore Fahrig

C19-Wild — spearheaded by University of Manitoba ecologist Nicola Koper — brings together conservation scientists from around the world, each gathering and sharing data on birds, mammals, reptiles and other animals in their regions. The project’s main study tracks birds in Canada and the continental United States.

While the nexus of Fahrig’s research has been to map negative human-inflicted impacts such as roadkill and habitat loss, the focus of C19-Wild, she says, “is to see whether we can detect a positive effect on birds as a result of the reduction in traffic, especially early on during the lockdown.”

To do so, the project used eBird observation app survey data from 2017 to 2019 in American and Canadian cities that have a population of 50,000 or more. It compared this data with bird surveys done since mid-March to determine whether there were any variations in bird distribution and population dynamics.

“By having hundreds of sites and by having variation in the sites and differences in the decrease of traffic, we got around the problem of the short timeframe,” says Fahrig. Luckily, birds are among the most documented of all organisms, she adds, so many of the study sites had a solid record of pre-pandemic data points.

“To ensure what we looked at was the effect of a reduction in traffic,” Fahrig explains, “we correlated bird survey data with cellphone records.” These show how many phones — and people — stopped moving every day. “Some cities had a big drop in traffic, others had a small drop, depending on the lockdown rules in the different jurisdictions,” says Fahrig.

“So what we could determine was, in places where you had a big decrease in traffic, did you get a higher number or occurrence of birds?”

The C19 team submitted its draft paper in early October and found, from looking at more than 4.3 million “bird detections” from spring 2017 to spring 2020, that of the 82 species assessed, 79 showed distribution changes during the pandemic — and that “increases in [bird] use of human altered areas with decreased traffic were much more common than decreases.”

Although the cause of these changes — less road kill or less traffic noise? — remains unknown, one conclusion is clear: human activity impacts much of the continent’s bird community. “From an environmental perspective, the pandemic is like a reversal,” says Fahrig. “It reinforces that the scale of human activity is too much for nature. If we are serious about reducing our impact on birds, we need to reduce how much we travel.”

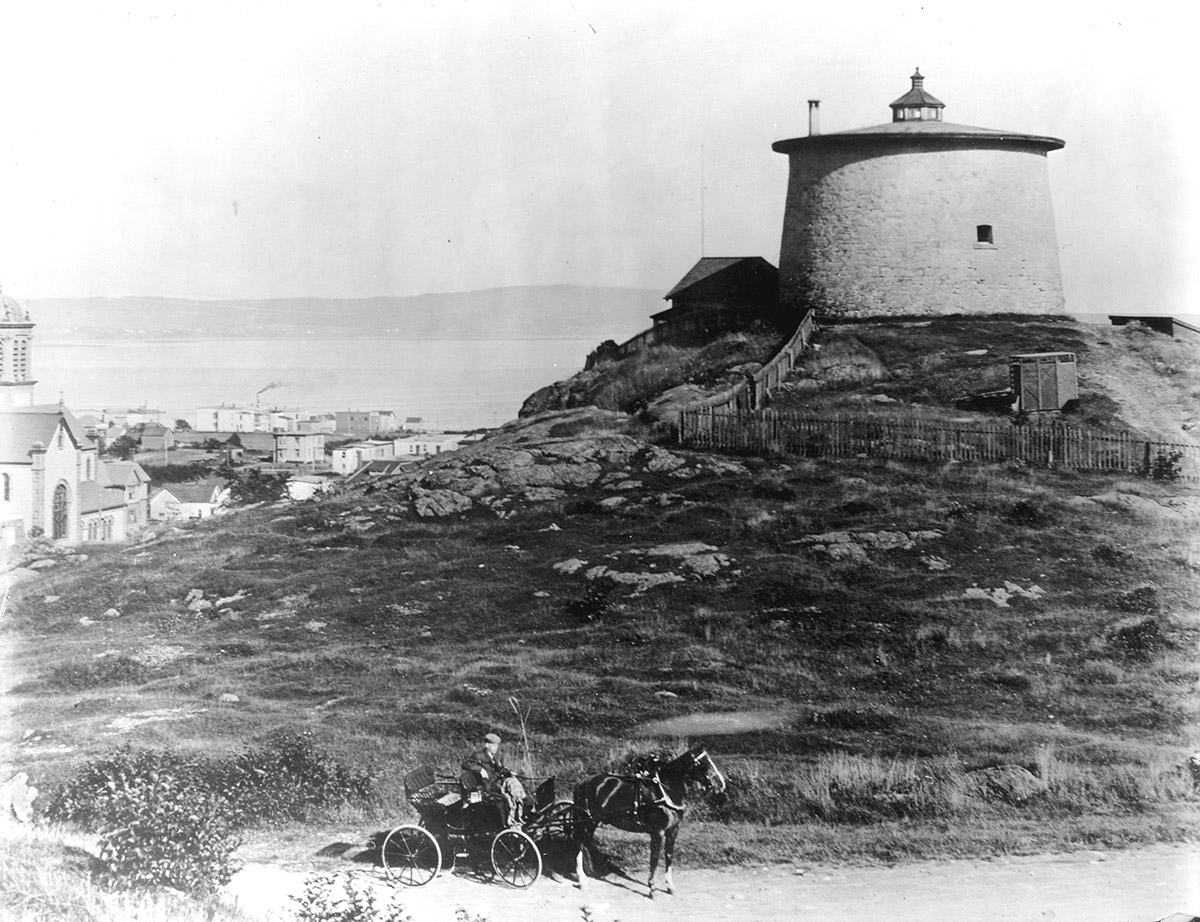

Carleton Martello Tower/Photograph courtesy Parks Canada

5. History From Home

Digital Heritage Conservation Doesn’t Stop

Finishing up her first year as an Architectural Studies student last spring, Sarah Mojeski was looking forward to a paid summer internship at the Carleton Immersive Media Studio. She was going to travel to Saint John, New Brunswick, to help create an immersive digital tour of the Carleton Martello Tower — a two-century-old National Historic Site that’s undergoing renovations — as part of the lab’s SSHRC-funded New Paradigms/New Tools training program. The pandemic put a stop to those plans, but Mojeski spent the summer working on the tower project from her home in Grimsby, Ont.

The Carleton Martello Tower was built in 1813 by the British military to help defend the city during the War of 1812. It has undergone five major renovations in its lifetime. In 1930, it became a National Historic Site — it has an amazing view over Saint John — but was put back into military use during World War II.

A fire command post was installed on top of the roof: a two-storey concrete structure for rangefinder equipment and harbour defence. That was so heavy it caused the walls to bulge, so Parks Canada is fixing that and doing other restoration work as part of a multi-year construction project.

Parks Canada wants to have a digital representation of the tower that people can experience while it’s undergoing construction and also to better meet universal accessibility standards. The tower is accessed from the exterior by a staircase that goes to the second level, and then the ground floor and the roof level are both accessed by staircases that aren’t wheelchair accessible. So they’re trying to make it possible for people to see the tower from home, which has become especially timely during the pandemic.

We’ve created a Building Information Model of the tower using point cloud data that they got before construction began. Point cloud data is generated by a laser scanner and creates an extremely accurate picture of the building. You can see the exact conditions and even what’s on the walls. We’re using that data and panoramic images of the tower to make a 360-degree video that will be posted to Parks Canada’s YouTube channel. It’ll provide an interactive way to “visit” the tower for anybody.

Not only do these types of immersive digital experiences help meet accessibility standards and allow people to see places from remote, you might learn some extra things about a site from a video that you wouldn’t know if you went in person. The technologies and software that we’ve been using can provide new perspectives on history. Digital heritage conservation will become even more important in the years ahead.

Connected Canadians co-founder Tas Damen helps a senior at a pre-pandemic session organized with Ottawa Community Housing

6. Tech Support for Seniors

Carleton Grads See Digital Literacy as a Human Right

By Brenna Mackay

Joan Cleary is a retired nurse who lives in a small town in Newfoundland. She has an active lifestyle: skiing, hiking and singing in the choir. When physical distancing measures were instituted, Cleary had to learn Zoom to stay in touch with friends. That’s when she discovered Connected Canadians, an Ottawa-based non-profit, started by two Carleton alumni, that provides older adults with the training and support they need to use technology safely.

“It was broken down in a way that I was very comfortable with it,” says Cleary, who was paired with a Connected Canadians tech mentor last spring.

“I wasn’t one bit intimidated.”

A few weeks later, Cleary’s brother passed away and some relatives couldn’t attend his funeral. But Cleary was able to video call them and bring her family together to grieve. “You can talk, you can laugh and you can cry — all through Zoom,” she says. “In this day and age, technology should be accessible to everybody.”

Connected Canadians client Marie with co-founder Emily Jones Joanisse

That goal is at the heart of Connected Canadians. Founded in 2018 by Emily Jones Joanisse (who has a bachelor’s degree in computer science and an MBA from Carleton) and Tas Damen (who earned a bachelor’s degree in computer science and math), the idea stemmed from their experience working in the software industry. When the women realized that they were frequently acting as tech support for the older adults in their lives, they saw an opportunity.

“We wanted to serve the community and not charge seniors any money,” says Damen, “because we strongly believe that digital literacy is a human right.”

Cleary’s story is just one example of how Connected Canadians is helping seniors at a time when people are relying on technology more than ever. To Jones Joanisse, the pandemic has emphasized how crucial it is to help seniors stay connected to their families and communities to curb their loneliness and isolation. “Prior to COVID-19, people thought of digital literacy for seniors as a luxury,” she says. “What we had been saying from the beginning has been validated and amplified.”

As social gatherings became virtual, Connected Canadians has seen an increase in requests for support. From teaching an elderly Catholic nun how to join her online spiritual circle to helping Ottawa’s Capital Pride seniors host virtual bingo nights, the organization has met this growing need by collaborating with organizations outside Ottawa and by training clients and volunteers across the country through online workshops.

The solutions they’ve come up with include a joint initiative with national charity HelpAge Canada that sees volunteers work with seniors to set up tablets that are sent to them for use in isolation, and a program that allows seniors to interact with one another online while playing language-based games. In May, Connected Canadians was awarded a grant from the City of Ottawa to retrain food and beverage industry workers who lost their jobs so they can become paid technology mentors. The organization now has 21 paid mentors on staff.

“It’s humbling to go from a startup to having national partners and large organizations such as the National Gallery of Canada and Apple that are impressed by our delivery model,” says Jones Joanisse, who, while remaining the full-time CEO, has returned to Carleton this fall to begin a PhD in management at the Sprott School of Business.

She plans to focus her thesis on how volunteering helps new immigrants integrate into the Canadian workforce.

Ontario Bioscience Innovation Organization President and CEO Gail Garland/Photograph by Giordano Ciampini

7. Homegrown Help

Getting New Technologies Into Ontario Hospitals Now

Gail Garland, who has a biology degree from Carleton, is the President and CEO of the Ontario Bioscience Innovation Organization (OBIO), a not-for-profit that, through partnerships with industry, investors, academia and government, supports the commercialization of human health science companies. OBIO’s Early Adopter Health Network (EAHN) — which connects health-care institutions with companies developing technologies that are ready for adoption — was launched in fall 2019 but quickly shifted gears to address COVID-19. Its first eight projects were announced in July and range from a portable dual x-ray device to a clinical decision support tool that can help physicians determine when to safely transition patients off ventilators.

When the pandemic hit, OBIO put out a call across Canada through the EAHN program for companies that were creating or adapting their technologies to help address COVID-19. We screened more than 75 applications and talked to the companies, assessing their technologies and the teams running these companies to determine their readiness. Then we selected eight initial companies and partnered them with hospitals. Those projects are in various stages of implementation, but we’re still working with the others that applied, and there are successive rounds of funding planned.

Hospitals see the merit of working with new technologies through the EAHN program because in many ways we’ve de-risked it for them. Hospitals are interested in evaluating new technologies, but the technologies and the companies developing them have to be ready. For this to work, hospitals have to be innovation friendly, which is largely cultural, and not every hospital is of that mindset. So we partnered initially with a small group of hospitals, and that list has grown extensively.

Most hospitals are innovation friendly if you go to them with technology that’s been vetted and can help their patients. Senior leadership at hospitals is also very interested in understanding the economic benefits of adopting innovative technologies. As we dialogued with industry, one of our key learnings was that industry didn’t know which door of the hospital to go through and were wasting valuable time trying to find the right people in a hospital, or the right hospital. Our model facilitates that for them, and the pandemic has put a fine point on the need to support innovation for the sake of innovation. Because you never know when you’re going to need it.

The EAHN gives Canadian companies that are evaluated within the Ontario health system the opportunity to stay and grow here. They don’t have to go to Boston or Silicon Valley because there’s an ecosystem here that will support the company through the development and commercialization process. And then we can export it to the rest of the world.

The pandemic has given us all an opportunity to understand why a robust health science sector here in Ontario and in Canada is critical. Whether it’s the next wave of COVID-19 or another crisis, we need to be prepared.

Yassen Atallah

8. Cross-Country Checkup

Co-Op Student Joins the Collaborative Health Care Innovation Secretariat

Last January, Yassen Atallah — a master’s student at Carleton’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs — landed a co-op position as a policy analyst at Health Canada’s Health Care Innovation Secretariat. He expected to work at the agency’s Ottawa office, applying his studies in international organizations and global public policy toward improving the country’s health care system. By the time he began his co-op from remote in May — a four-month post that has been extended to the end of December — the landscape was different.

Like every other organization, the public service wasn’t totally prepared for this pandemic. We’ve adapted very well, but when I started it was like being put in the middle of a forest fire: everybody was running around trying to put it out and I was trying to find the buckets and the water. My training wasn’t traditional. It was, “Here’s a bunch of tasks, you’re going to learn as you go.” So from day one I just started helping wherever I could.

The secretariat is juggling a number of COVID-19-related files on data policy, digital tools, health innovation and bilateral agreements between the federal government and our provincial and territorial partners. We’re also negotiating funding agreements with provinces and territories so that they can improve their virtual care capacity. Generally speaking, any policy or research or funding is primarily focused on COVID-19, but we also understand that the implications of this work can reach beyond the pandemic.

I’m especially passionate about assisting with the Canadian Health Information Forum. Our team supports biweekly meetings with federal, provincial and territorial associate deputy ministers and other senior government officials to discuss Canada’s COVID-19 response and how governments and other pan-Canadian organizations can work together to address health data gaps and priorities. This is important as the availability of and timely access to data is needed to understand, monitor and respond to the pandemic.

My responsibilities include analyzing federal, provincial and territorial objectives and needs, as well as preparing the logistics for each of the meetings. The forum is a really dynamic, fast moving group — we tackle a number of topics every meeting — and lessons learned in various provinces and territories can lead to a more effective response to COVID-19.

It’s pretty cool to see how provinces and territories aren’t just focused on their own jurisdictions. They’re communicating with one another and sharing knowledge. That’s really inspiring, because to make a significant change we need to work collectively.

Working at Health Canada has allowed me to gain invaluable insight into the inner workings of health ministries and how they navigate complex crises to deliver a wide range of services. Ever since my undergrad, I’ve wanted to be at the intersection of the social and natural sciences. Being at Health Canada during these trying times has provided me with a great opportunity to apply my policy skills to improve the lives of some of most marginalized people in Canada.

Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre director Mara Brown/Photograph by Fangliang Xu

9. Virtual Community Hub

The Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre Leapfrogs Into the Future

By Sissi De Flaviis

On a cold April day, Mara Brown walks into her workplace in downtown Ottawa, closes the door and confronts a strange reality. She is absolutely alone in a 37,000-square-foot building.

As the director of the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre (CDCC) — the historic church that the university has transformed into an arts, performance and learning space — Brown is responsible for managing everything from renovations to events that bring audiences into the building. Which is a major challenge when COVID-19 has put an abrupt halt to mass gatherings.

“When there isn’t any activity in a building, it starts to lose physical integrity and energy can drain out,” says Brown. “The empty space was daunting at first but became inspirational pretty quickly, walking the halls and dreaming about the great future to come.”

The word “pivot” is overused when talking about how organizations have responded to the pandemic, but it certainly applies to the CDCC. After welcoming more than 85,000 people in the 10 months leading up to lockdown, the centre will now be fulfilling its cultural and academic role in an entirely unexpected way.

With organizations such as the Ottawa Symphony Orchestra, Music and Beyond and Ottawa Chamberfest unable to hold performances, the CDCC turned its multi-year master plan upside down and quickly became a venue for livestreaming and recording concerts.

“We always knew we wanted to have high-tech audio-visual equipment and infrastructure throughout the building, but we imagined doing this much later,” says Brown.

“Suddenly, we have recognized an opportunity to provide options for people to perform and reach those who are experiencing sustained isolation. It’s been strange and amazing to flip our planning on its head.”

Overcoming the logistical challenge of setting up new technology in an old building, as well as shipping delays due to the pandemic, the CDCC has installed an array of equipment: cameras, tripods, lenses for capturing close-ups and wide shots, switchers for changing angles, software to process video content and more than 3,300 feet of cable.

Ottawa Chamberfest helped test the new equipment and hosted a six-part livestreamed concert series at the centre this fall. A team from the local Rogers TV station recorded three days of performances in June with the Music and Beyond virtual summer festival, which was previously an in-person experience and is now online. The Rogers recordings not only brought life to the centre but also helped the broadcaster create cultural content — such as a collaboration with the Ottawa Symphony Orchestra at the CDCC in September — and fill the gap from the loss of live events in its schedule.

While the resumption of in-person activities still needs to be mapped out, the CDCC hopes to support small recitals by music students who must do live performances to graduate. Meanwhile, the doors opened in September to the United Church congregation to resume on-site worship, albeit with physical distancing and strategic seating.

“It is fair to say that large group gatherings will be one of the last things to return,” says Brown, “but it is fascinating to witness the rapid evolution of how we’re sharing art through online technologies. In-person gatherings can never be replaced, but one of the best things about creative industries are the people who have the ability to problem solve and evolve.”

Andrew Simpson

10. Cultural Healing

How a Social Work Practicum Helped Me Find My Niche

Andrew Simpson earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degree in social work at Carleton. Born and raised in Bancroft, Ont., and of Métis ancestry, he works for Dnaagdawenmag Binnoojiiyag Child & Family Services, an Indigenous well-being agency based at Hiawatha First Nation with more than 20 offices spread out over eight First Nations and off-territory towns in south-central Ontario. Simpson started at the agency — which provides culturally based wraparound services to children, youth and families — for his grad school practicum last spring and was hired on as a full-time family service worker.

In this field, people allow you into their world. You play an active role in the lives of individuals and families, helping to connect them to community support. One of the most difficult aspects of this job is fighting the urge to jump in and try to fix problems yourself. Each person or family has their own blueprint, and you work with them to identify and connect to the resources they need.

There’s no cookie-cutter approach. They are the guides, and you need to take the time to listen to their stories and find the right way forward. You need to step back, take a breath, ask questions and allow people to be heard, and then work as a team to alleviate some of the challenges they’re facing.

We integrate culture into the healing process and help reintroduce people to their cultures. That’s been the most beautiful thing that I’ve seen. Indigenous cultural practices have the ability to connect people to each other and to their communities and, at the same time, they challenge colonization.

Trying to navigate Indigenous services and supports in Canada can be difficult, but these are things that our communities need and I’m proud to be part of this journey. As a social worker and as a social justice warrior, I want to help fix the system we live in for the betterment of the people who we support.

My mom is also an Indigenous social worker. Through her and through my aunties, I started to connect with my culture while growing up. As I got older, I started to dig into things more deeply on my own and was exposed to ceremonies and teachings from Elders. It’s definitely been a reconnection for me.

When the pandemic began, I was grateful for the technology that we had, because it allowed us to still connect with families while distancing. We transitioned some of our cultural programming online without skipping a beat. But it was difficult, because a lot of the sense of community we have was built through face-to-face interaction, so I was really happy when we were able to resume seeing people in person in some situations, including visits outside in parks. It meant a lot to see people’s faces — not on a screen — again.

I hope COVID-19 reinforces the importance of community. I hope that people slow down and take the time to be kind and loving and take small steps to help others. Even if it’s a little thing, it could mean something big to someone else.

Monday, November 23, 2020 in Features - Fall 2020

Share: Twitter, Facebook