Becoming Migration Researchers: Disquieting Borders with Auto-Ethnography

An introduction to “Migration Stories” by Laura Bisaillon

What do five Canadian women with kinship ties to Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Vietnam have in common? Quite a lot, as it turns out.

In this special collection, contemporary experiences with human movement and circulation across borders, both material and conceptual, are analysed. The features of these movements—what they look and feel like, and what opportunities and challenges mobilities impose on people on the move—are examined ethnographically from five distinct perspectives. These perspectives come from five thoughtful young women: Danica Bui, Fatema Motiwala, Fatima Haque, Nawrose Khan and Sarah Syed, all of whom grew up in immigrant homes in the eastern suburbs of the Greater Toronto Area, Canada.

The broad aim of this series is to problematize the ways in which cultural, political and spatial boundaries produce tensions for migrants and their kin starting within routine, perhaps overlooked, and otherwise taken-for-granted situations of daily life. This focus on the social, where people are not the objects of analysis per se, situates this series within the social organization of knowledge approach in sociology (Smith, 2006). The strategy of confronting the problems of biography, culture, history, structure and their intersections by beginning in the conditions and concerns that we see, hear about, or which impact on us, connects this volume within the sociological imagination approach (Mills, 2000).

From Practice to Theory—and Back Again

The five contributing authors were fourth-year undergraduate students in my Migration and Public Health course, which convened from September to December 2018. A delightfully dialogical and intimate seminar-style class, I have offered it for the past four years at the University of Toronto Scarborough. Through it, students emerge with better understandings of ideas in diaspora, emigration, forced migration and immigration studies. They engage with the humanities and interpretive and critical social sciences’ literatures. In my teaching, I foreground scholarship produced by Canadian or Canadian-trained scholars. I am strongly committed to having students know and immerse themselves in the preoccupations and priorities that scholars in their home society have studied and debated rather than those imported from U.S. society, for example.

Through this twelve-week course, students gain awareness about social processes that underlie, produce, and sustain human movement across time, space and place. They engage with migration histories—their own and those of their kin, those of their classmates and me, and other people beyond their immediate experience whose lives they only know through the refraction of the media’s lens. Finally, students develop new and socially situated knowledge for thinking about how migrants experience criminal, education, immigration, legal, and medical systems in Canada and beyond by examining how migrants interact with these institutions.

By the end of term, students develop the ability to answer questions such as:

What themes surface again and again in the migration literature? How do classification systems such as state health and demographic registries shape how we understand migrants and ourselves? How do gender, health status, racialization, sexual orientation, and social class influence migration experience?

For the culminating project, students produce auto-ethnographic analyses. This form of analysis starts a social researcher in problematics that are compelling to them (Portelli, 2017; Riggan, 2014; Taber, 2012). This is the springboard for exploration into and critique of cultural, political and spatial relations, and in this collection, those that are germane to contributors’ lives as migrants or offspring of migrant parents. Importantly, students learn to produce re-search—as distinct from me-search—where they connect the dots between private troubles and social problems: tethering their ideas to those of researchers in anthropology and sociology (Anton, 2013; Bernal, 2017; Bisaillon et al., forthcoming; McCoy, 1995), education and social work (Sakamoto, Chin & Young, 2010; Shan, 2013), and history (Calliste, 1993; Eidinger, 2014; Gabaccia, 2010; Iacovetta, 1995; Spagnuolo, 2016).

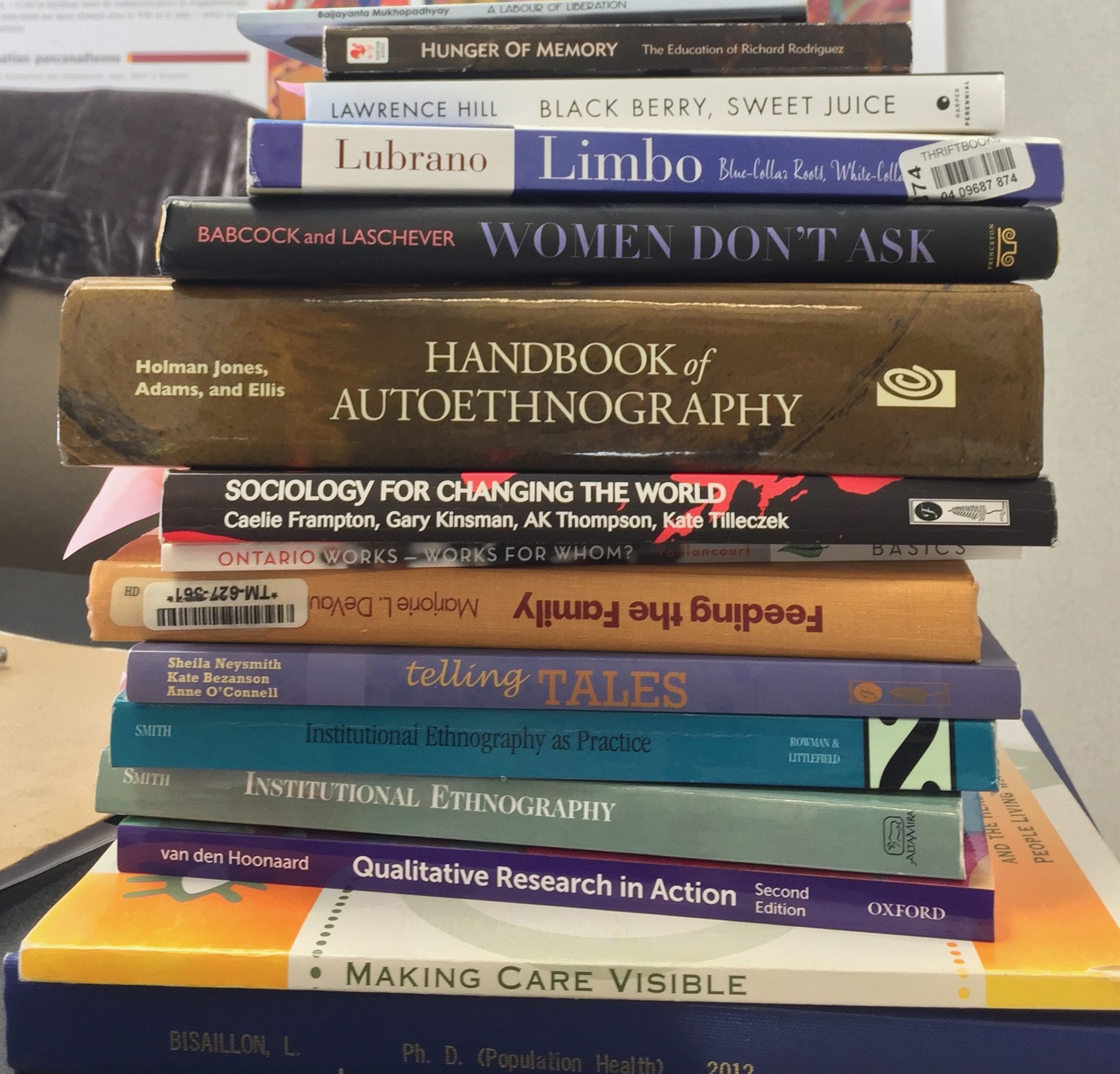

Anthropologist Shahram Khosravi’s (2010) non-fiction ‘Illegal Traveller’: An Auto-Ethnography of Borders is the intellectual centerpiece for this course and its textbook. On offer is a deeply poetic, personal and incisive critique of the nation state system. Khosravi argues that since this system causes demonstrable harm—as the events of his life and the lives of others storied into this book, living and dead, testify—, it must be dismantled. Because this system presses down most harshly on people in the social margins, his arrow is aimed at talking back to how racialized and working class people, and those who belong to language, ethnic and religious minorities, among other groups, are positioned to experience borders and bordering practices troublingly. ‘Illegal Traveller’’s topical focus and evocative narrative form, and the author’s use of social theory to frame his fieldwork, have made this book a strong resource for students; a fine example that helps students figure out what to say, how to say it, and how to use social theory in their essays.

From Asia to North America

In the first essay, “From Vietnam to Canada,” Bui recounts a 2017 trip to Vietnam with her brother, Allan, and father, Duong. We learn of her and her father’s shared love of photography, and in her essay, she includes two of her own photographs and one her father took on this trip. Using digital cameras, they have captured a specific setting (domestic compound), people (father and brother), and a structure (family home). She uses silent and spoken interactions behind the lenses, the materiality of the setting, and the discursively organized features of her father’s story telling about his complicated relationship with Vietnam and also the numerous other countries through which, in forced flight, he needed to transit, until eventually settling in Canada. Her essay is meditative and artful. Through it, we are privy to a story within a story: a father talking to his children about what it was like to grow up in this home, and a daughter interpreting her father’s fraught relationship with this place. Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, Bui muses, her father seems to find rootedness in mobility and transience and also in the anchoring that a structure such as a house is conventionally thought to bring.

“Language Past, Present and Future” is Motiwala’s essay that situates us in fifteenth century India with the origin story of her ethnic group, Memon, and language, Kutchi. She descends from a long line of Muslim “sailor businessmen” who migrated into Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, and more recently, North America. Motiwala problematizes the gains and losses of permanent migration. Specifically, she asks questions about the Kutchi language, which is entirely oral and currently without an alphabet, and the possibilities for its continued existence beyond the present. Her carefully crafted concerns are fully existential: she identifies language as the purveyor of cultural practice. We follow along as she questions, and tentatively imagines, the implications of a language being forgotten. These issues are discussed by Memons around the world. She argues that Kutchi must be preserved. While the position is understandably sentimental, given that her mother tongue might well run extinct, it raises concerns that scholars of the politics of minority languages and memory studies have long debated. Motiwala draws on these literatures, presenting original ideas about remedial steps that she suggests could assist Memons to re-engage with and re-learn their historic language.

“The first time I recall seeing my father nervous was at the U.S./Canada border.” This is the opening sentence in Haque’s essay, “From Asia to North America.” Racialized people, those working without official paperwork in the European Union, Canada or the United States, for example, and people with passports issued by countries other than the latter have felt the profound sense of trepidation she describes. They have lived or will live similar situations because of how they look or the socially organized impotency of their passport (Torpey, 2000). Social otherness is the ideological concept organizing this essay. The social suffering of being ‘othered’ as a form of social violence is its empirical ground (Said, 1994). A religiously observant Pakistani Muslim, Haque and her kin continue to find post 2001 hostilities toward Muslims difficult, which has shaped their choices about where and how to live. To illustrate, she discusses decisions that she and her mother have taken about performing religious rituals (praying, fasting) and using religious artifacts (prayer mat, hijab). Through Fatima’s eyes, we see religiosity as part action, part reaction. In her lifetime, religious activities have produced calm, coherence, continuity and community connection.

Khan’s “Growing up in a Bengali Kitchen” opens with a scene of her returning home to the smell and sight of her mother preparing a meal for the family to break fasting together. Situating herself in the everyday, she turns to examining food and “what we cook and eat at home.” Specifically, she studies the shil batta, which, in Bangla, means grinding stone. We learn that this tool is a key component of the family kitchen. Symbolically, it connects them with people and practices in Bangladesh. Through conversations with her parents, she explores how this item was used in their respective childhood homes, while also reflecting on how the family uses it now. She juxtaposes her younger and older selves in a discussion about growing confident about social difference, manifest in food culture, juxtaposed against an ideological or so-called “Canadian culture.” While it might be possible to read this essay as a coming-of-age story (and since she tells a good ethnographic story, the reader is in for a treat), its value, rather, lies in what we learn from Khan’s absorbing analysis of social belonging and tensions and contradictions it triggers in a migratory context.

Finally, Syed’s essay, “A Song for my Mother” is a tribute to her mother who left the Philippines alone and settled in Canada when she was about Syed’s age. In asking her mother to share details of her migration experiences, Syed learns about, and is moved by, all of the big and small effort and incredible challenges the process involved for her mother; seeing her as the woman she was in the years before becoming Syed’s mother. (Other students have experienced and reflexively analyzed this combination of surprise, attending to and illumination in the past years, with the mother-daughter and father-son relation, most commonly contemplated; see Lepucki, 2017 for a daughter’s homage to her mother’s womanhood.) Being a singer and songwriter, she takes guitar in hand to create an original audio-visual musical composition that she includes as part of her essay. Through interpretation of the lyrics, included herein, she contests the ‘us versus them’ binary for how it fails to acknowledge human interdependence, which hitches her work to the critical migration literature. Further, she disputes the concept of ‘vulnerable’ as applied in de facto fashion to migrants. Her mother’s socially ascribed vulnerability has actually revealed itself in qualities such as increased openness, receptivity and empathy, which Syed argues are the attributes we must prize in migrants and us. A mature and humanist contribution, her piece makes a unique methodological contribution.

From Classroom to Media Lab

It has given me abundant joy to see how auto-ethnography as a methodological strategy has alighted students’ imaginations and enlivened their ability to arrive at nuanced considerations about the ‘hot button’ topic that migration has become in the last years. The maturity and quality of student work has very often exceeded my expectations. My hunch about why students have responded so well to this approach and the course’s topical focus is multilayered.

Part of what students must do is work reflexively and in cooperation with each other inside and outside of the classroom. This sees them nestling down into several ideas, identifying passages and words that stir them, for whatever reason, rather than surveying the literature. Individually and together, then, they rehearse their ideas orally and in writing, which invites and makes way for them to contemplate deeply rather than superficially. What is more, Bui, Motiwala, Haque, Khan and Syed care about the people, places and politics they investigated ethnographically. Working from inside their homes in an outward direction, they became exhilarated to realize that scholarly inquiry can, indeed, begin from situations of everyday life. Specifically, from those things which are bothersome or unresolved. As they come to see, the questions they set out to explore have, actually, been nagging at them for some time, as latent features of their lives. Something wonderful and unexpected, for me, is how, through the sequenced assignments, students engage their relatives intellectually: they mobilize course concepts and pursue lines of questioning that, until then, they report, were underexplored, if explored at all. In fact, students devour Khosravi’s book. They read it from cover to cover, in record time, and come to class describing how its ideas informed discussions with their kin precisely because they saw themselves and the experiences of their families, as classed, ethnic, linguistic, racialized, or religious minorities, in its pages.

Finally, we propose this collection as both a scholarly and activist endeavour. It was birthed from an iterative, behind-the-scenes process that began alongside ten other classmates with whom contributing authors shared their earliest ideas about what appears herein. Our process drew together a seasoned researcher (me) who taught five fledgling social researchers (Bui, Motiwala, Haque, Khan, and Syed) to exercise scholarly skills of supporting argumentation, organizing ideas, and writing a good ethnographic story, in parallel with social competencies such as patience, perseverance, and intellectual humility; all necessarily deployed within scholarly publishing. From January to July 2019, we convened working meetings in person and via computer screens, while making productive use of materials within the course’s Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/groups/migrationpublichealth/). I started this public page in 2016 as a way of building and maintaining communication with my students both during the period they are enrolled in my classes, and often for a year or more afterward. In cultivating epistemic communities topically organized by course ideas, I aim to strengthen students’ sense of connection to their university, while also demonstrating to them, through the sharing of ideas that happens on this page, that education is a life-long, effortful and enriching process. These forums also serve as valuable living repositories of course-related materials where students past and present and scholarly colleagues from around the world provide nourishing content. What is more, this translocal engagement sustained over time stands to help me realize a longer-term goal: to curate a collection of essays by successive generations of students in this class. In sum, in the footsteps of a long line of feminist scholars who have come before us, the six of us took time to listen to each other, accept ambiguity, mature ideas, and exchange draft writing in several rounds (Bisaillon et al., forthcoming; Greenhalgh, 2019); intentionally making the most of “the tools of social science, friendship, and the power of conversation” (Mountz 2016, p. 207) to produce a series more valuable than the sum of its parts.

This volume is simultaneously activist and subversive. It presents original analysis that valorizes social standpoint. Importantly, contributors show understanding of the value of training oneself away from employing a theoretically over-determined stance because it can and often does elide experiential knowledge. Instead, as my of program of research and these essays demonstrate, a materialist starting point, one which detects and bravely tackles social problems head on, carries the potential to matter for people experiencing social marginality, be these other people or ourselves, since it gets at the heart of what is amiss. Lastly, this series conceives of the undergraduate classroom as a site of knowledge co-production.

In closing, a key challenge to which the authors rose masterfully was to fuse critical and creative ways of knowing on the one hand (Finn, 2015), while engaging poetically and politically (in a world tilted painfully to the right) on the other. In envisioning this series, our desire, Danica, Fatema, Fatima, Nawrose, Sarah and my own, was to evoke and reveal the world we inhabit in thoughtful and novel ways. We hope that our readers will agree that we have succeeded in our mission.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Carleton University Professor Merlyna Lim, Canada Research Chair in Digital Media and Global Network Society, along with Kathy Dobson, doctoral candidate and author (With a Closed Fist and Punching and Kicking), of the Alternative Global Network Media Lab. As the project’s earliest enthusiasts and steadfast supporters, their intellectual and editorial leadership were mighty valuable and very much appreciated.

References—Suggested Reading List

Anton, L. (2013). On Memory Work in Post-Communist Europe. A Case Study on Romania’s Ways of Remembering its Pronatalist Past. Anthropological J of European Cultures, 18(2), 106-122.

Bernal, V. (2017). Diaspora and the Afterlife of Violence: Eritrean National Narratives and what goes Without Saying. American Anthropologist, 119(1), 23-34.

Bisaillon, L., Montange, L., Zambenedetti, A., Frasca, P., El-Shamy, L., & Arviv, T. Everyday Geographies, Geographies in the Everyday: Mundane of Mobilities Made Visible. ACME: An International Journal of Critical Geographies (forthcoming).

Bisaillon, L., Cattapan, A., Driessen, A., van Duin, E., Spruit, S., Anton, L., & Jecker, N. Doing Academia Differently: ‘Needing Self-help Less than a Fair Society’. Feminist Studies (forthcoming).

Calliste, A. (1993-94, Winter). Race, Gender and Canadian Immigration Policy: Blacks from the Caribbean, 1900-1932. Journal of Canadian Studies, 28(4), 131-148.

Eidinger, A. (2014). Looking Jewish: Embodiment of Gender, Class, and Ethnicity among Ashkenazi Women in Montreal, 1945-1980, Social History, 47(95), 729-746.

Finn, P. (2015). Critical Condition: Replacing Critical Thinking with Creativity. Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Gabaccia, D. (2010). Nations of Immigrants: Do Words Matter? The Pluralist 5(3), 5-31.

Greenhalgh, T. (2019). Twitter Women’s Tips on Academic Writing: A Female Response to Gioia’s Rules of the Game. Journal of Management Inquiry, 18, 1-4.

Iacovetta, F. (1995). Manly Militants, Cohesive Communities, and Defiant Domestics: Writing about Immigrants in Canadian Historical Scholarship. Labour/Le Travail, 36(Fall), 217-252.

Khosravi, S. (2010). ‘Illegal Traveller’: An Auto-Ethnography of Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan.McCoy, L. (1995).

Lepucki, E. (2017, May 10). Our Mothers as We Never Saw Them. The New York Times Opinion. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/10/opinion/our-mothers-as-we-never-saw-them.html

McCoy, L. (1995). Activating the Photographic Text. In M. Campbell & A. Manicom (Eds.), Knowledge, Experience and Ruling Relations (pp. 181-192). Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Mills, C. (2000 [1959]). The Sociological Imagination. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mountz, A. (2016). Women on the Edge: Workplace Stress in Universities in North America. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien 60(2): 205-218.

Portelli, J. (2017). Xewqat tal-Passa/Migrant Desires. Qormi, Malta: Horizons Malta.

Riggan, J. (2014). Biopolitical Departures: A Love Story. Journal of Narrative Politics, 1(1), 44-60.

Said, E. (1994 [1979]). Orientalism. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Sakamoto, I., Chin, M., & Young, M. (2010). ‘Canadian Experience,’ Employment Challenges, and Skilled Immigrants: A Close Look through ‘Tacit Knowledge.’ Canadian Social Work Journal 10(1), 145-151.

Shan, H. (2013). The Disjuncture of Learning and Recognition: Credential Assessment from the Standpoint of Chinese Immigrant Engineers in Canada. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 4(2), 189-204.

Smith, D. (ed.). 2006. Institutional Ethnography as Practice. Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Spagnuolo, N. (2016). Defining Dependency, Constructing Curability: The Deportation of ‘Feebleminded’ Patients from the Toronto Asylum, 1920-1925. Histoire sociale/Social History, 49(98), 125-154.

Taber, N. (2012). Beginning with the Self to Critique the Social: Critical Researchers as Whole Beings. In L. Naidoo (Ed.), An Ethnography of Global Landscapes and Corridors. London, UK: InTech Publisher.

Torpey, J. (2000). The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.