Welcome to Noah’s Blog

BA Honours English (2022); PhD Literary and Cultural Studies, ongoing

Noah Bendzsa is a fourth-year Honours English student. They studied mathematics and chemistry, successfully and unhappily, until discovering that they could study novels and short stories instead. Although they sometimes miss hearing about “Gödel and His Problems,” they have not looked back. In their spare time not spent reading, they enjoy going for walks and hikes. They are a would-be Peakser, so long as they don’t wash up “wrapped in plastic.”

Table of Contents

March 31, 2022

Shocks in a Clown-Shaped Box

Between the ages of twelve and fourteen, my friends and I were addicted to feeling shocked, scandalized, thrilled, chilled, freaked-out. We loved horror movies with leaping danger and sudden, discordant sounds, and creepypastas—short stories published on the internet that are scary as long as you don’t contemplate their logic (“If my dog was dead, who was licking my leg, in the dark?” and that kind of thing). Interestingly, though, none of us had read Stephen King. Everyone we knew who had grown up in the seventies and eighties—parents, teachers—regularly adduced King’s books, in conversation, as the scariest things they had ever read. Carrie, Christine, Cujo, The Shining, and It were household names, like Bran Buds. And like Bran Buds, they were nothing we had ever tried.

When I was fourteen, I finally took Carrie out of the library. It bemused me more than it frightened me. Nineteen-seventies culture was odd, and I couldn’t quite figure out the characters’ motivations. What I remember most vividly is identifying quite strongly with Carrie’s friend, the one who, at the end of the book, is left wandering a field somewhere—though I can’t recall her name. Although I liked Carrie well enough, I moved on to other things, and until recently hadn’t had any urge to read another Stephen King novel. A few weeks ago, I got the urge.

The novels I read were ’Salem’s Lot and It. I started reading them because I have an obsessive interest in regionalism, or local colour—of which I had heard King is a specialist—and I finished reading them because their writing surprised me. King is not, as Harold Bloom blustered, “an immensely inadequate writer on a sentence-by-sentence, paragraph-by-paragraph, book-by-book basis” (qtd. in Ciabattari, 2014). He is a talented writer who works with mature themes and is sometimes capable of genuinely beautiful prose and imagery.

Admittedly, ’Salem’s Lot is not superbly strong, but it is only King’s second novel. And it certainly delivered on its regional promises (and in high gothic fashion): the best writing in the novel comprises descriptions of the fictional town Jerusalem’s Lot, Maine. Nonetheless, a lot of the other writing, including the horror, is boilerplate. The protagonist’s love interest, like many of King’s women, apparently, is repeatedly described as “pretty” (as in, she has pretty much the depth of the woman from the Roy Orbison song). Characters’ emotions can often be read off their faces, like those of the characters in a sitcom. And King’s musings about evil and the haunted house on the hill are clumsy. The word “haphazard” is used in a description of the house, and then, as if readers don’t get the point, “haphazardly” is used a few lines later (King, ’Salem’s 24). The echoes of Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House and Wallace Stevens’s “The Emperor of Ice Cream” are too frequent, and the internally rhyming sentence “Hail Mary, full of grace, help me win this stock-car race” is embarrassingly like something a teenager might write (241). (I should know, because that’s the kind of stuff I wrote as a teenager). But as a whole, ’Salem’s Lot is an entertaining work, and the last 150 pages read very, very quickly—to King’s credit as a haberdasher of plot.

It is an entirely different work and an impressive novel, without qualification. It was published ten years after ’Salem’s Lot and showcases King’s development as an artist. It is a masterclass in structure. Over 1100 pages long, the text jumps back and forth between 1986 and 1958, and across more than a dozen different focalizations. Certainly, King doesn’t worry over his sentences like Henry James or Jean Stafford or Shirley Hazzard, and many are duds. Though none are any worse than many of those authored by the most-praised contemporary “literary” writers (see B. R. Myers’s manifesto), and the book contains some truly beautiful passages. Consider the focalized description of a boy getting his first bicycle, named after the Lone Rider’s horse, Silver, up to speed:

He pedaled down Kansas Street toward town, gaining speed slowly at first. Sliver rolled once he got going, but getting going was a job and a half. Watching the grey bike pick up speed was like watching a big plane roll down the runway. At first you couldn’t believe such a huge waddling gadget could ever actually leave the earth—the idea was absurd. But you could see its shadow beneath it, and before you even had time to wonder if it was a mirage, the shadow was trailing out long behind it and the plane was up, cutting its way through the air, as sleek and graceful as a dream in a satisfied mind.

Silver was like that.King, It 226

King’s diction doesn’t always strike the right note, as this passage demonstrates (is an airplane really a “waddling gadget”?), but the whole is an amazing trick. Anyone who has ever ridden a bicycle and has pushed it to thirty-five or forty kilometres per hour feels what’s being described, here. The experience is like that.

Later on, one of the male protagonists, Ben, returns to his hometown, the fictional Derry, Maine. “He walked across the library lawn, barely noticing his dress boots were getting wet, to have a look at that glassed-in passageway between the grownups’ library and the Children’s Library,” King writes;

[i]t was also unchanged, and from here, standing just outside the bowed branches of a weeping willow tree, he could see people passing back and forth. The old delight flooded him, and he really forgot what had happened at the end of the reunion lunch for the first time. He could remember walking to the very same spot as a kid, only in the winter, plowing his way through snow that was almost hip-deep, and then standing for as long as fifteen minutes. He would come at dusk, he remembered, and again it was the contrasts that drew him and held him there with the tips of his fingers going numb and snow melting inside his green gumrubber boots. It would be drawing-down-dark out where he was, the world going purple with early winter shadows, the sky the colour of ashes in the east and embers in the west. It would be cold where he was, ten degrees [Fahrenheit] perhaps, and chillier than that if the wind was blowing from across the frozen Barrens, as it often did.

543–44

Although It is inarguably a horror novel, it is also delightfully ruminative, and explores serious themes of childhood remembrance, belonging and ostracism, and friendship and the bonds between people. If any of that sounds familiar, it’s because those are some of the same things that Proust writes about in À la recherche du temps perdu—for instance. I’m not trying to imply that King is “our Proust” or as even meticulous a writer as Proust; all I’m trying to say is that saintly feet have walked this ground before.

I should remark, though, that It’s status as horror is not as straightforward as you might assume—as I assumed—at least, not for a non-coulrophobic adult reader. Before I began the book, I understood its horror elements to consist of a shapeshifting clown called Pennywise (or an eternal spider-thing that sometimes takes the shape of a clown called Pennywise) and his various forms. But the portions of the book about the clown, the clown-cum-teen-werewolf, -cum-mummy, -cum-Honda-Civic-sized-chickadee aren’t scary. These are childhood fears, and may be the things that tweens and teens find frightening when they pick up the book. They certainly would have been the scares my friends and I were after at thirteen. What’s really horrifying for an adult reader, though, are the human acts of violence, for which the clown is only a catalyst. I’m not sure if Henry Bowers resembles any real fifth-grade bully, but his homicidal tendencies make you angry, make you feel powerless, make you really fear for the kids in his sights and wish you were there to give him a few whacks with a sand-filled hose. This is how we are made to feel about a twelve-year-old. And then there’s the protagonist Beverly’s abusive husband, Tom; the scene in which he beats Bev’s whereabouts from one of her friends, and then threatens to come back and kill the friend if she calls the police, is hard to read. It’s awful and all too real.

But Tom’s violence is not the only violence based on a—based on many a—true story. After the famous clown-in-a-storm-drain opening, which even those who haven’t read the book know about from the 1990 miniseries, comes the first murder of the clown-creature’s new cycle. Except this murder is not perpetrated by the clown. Pennywise, although he snacks on the corpse, as he is wont to do, is essentially a bystander. The victim is a gay man, Adrian Mellon, and the murderers are a pack of rabid homophobes. It is these banal and intolerant human characters who “stab [Mellon] seven times,” before throwing him over the side of a canal (38). The episode is based on the real-life killing of Charlie Howard in Bangor, Maine, in 1984. But hate-crimes against LGTBQ folks—like spousal abuse, like violence against women—are frighteningly commonplace. This murder isn’t the reified fear of a desiccated corpse. One of my friends has had to lie about his sexual orientation before because feared for his life. We’ve all been in a situation where we’ve had to keep quiet because it’s safer, and we’ve all read or heard stories about people who have been badly hurt, or died, if we haven’t known a survivor personally. That’s terrifying.

There is received wisdom, other than that about the scares, that turns out to be wrong, too. First, there is the assumption, upon which the two-“chapter” adaptation of It from 2017 and 2019 is based, that the novel is actually a pair of novels grafted together: a protagonists-as-children novel, set in 1958, and a protagonists-as-grownups novel, set in 1985. A diligent structural reading reveals that these two “novels” are not separable. The as-adult sections might be surgically removed from the as-children sections, but unlike the as-children sections, they would not be able to survive on their own; they rely too heavily on flashback and recollection, and the scenes that result from these techniques constitute parts of the as-children section. The above-quoted scene from the as-adults section, when Ben returns to Derry, for example, is anchored in the winter scenes of the as-children section.

Then, there is the notion that “what amounts to an orgy” takes place amongst the seven protagonists, in one of the sections set in 1958 (Smythe, 2013). What happens is the six male protagonists have vaginal sex with the female protagonist, Bev, at her instigation. Doubtless, for some the scene will be discomfiting and feel voyeuristic, although I suspect this is age dependent. The protagonists are eleven- and twelve-year-olds, and the reader—at least, this reader—and the writer are much older. Overstating the case somewhat, we might ask, “Does this scene amount to the promotion of some kind of meta-literary pedophilia?” Without appealing to King’s intentions, I think we can answer “No” to this question and its variants for two reasons. First, there are a fair number of sexually active eleven- and twelve-year-olds; the scene, if improbable, is realistic in the sense that children become sexual subjects (in the self-forming sense of “subject”) around this time in their lives. Second, the sex isn’t exploitative of the characters, or especially explicit within the text. Bev uses sex strategically, and its purpose is to renew the bonds of friendship amongst the participants. She isn’t objectified during the scene; in fact, in a pleasant inversion of many adult-heterosexual-sex scenes, it is her pleasure that is central, and most of the male characters are unable to ejaculate. (Oddly, this appears to be for developmental rather than psychological reasons).

For folks in English studies, the most controversial thing about It, or any of Stephen King’s novels for that matter, ought to be their literary status. Are they Literature or are they mass entertainment, pulp, penny-dreadfuls, or whatever else you want to call the negation of Literature? This question, popping back up like a clown-shaped punching-dummy whenever someone thinks that they have successfully put it down, is one of the eternal questions of our discipline that many pragmatic people wish would just go away. It is interesting to study why people hold the beliefs they do about Literature, and what it means that literature has been defined this way (with a capital L), rather than that way, but Is It Literature? is largely irrelevant as a question in and of itself. The great Literature Debate is a debate in the same way that “Who would win—Darth Vader vs. Kylo Ren, Jaws vs. Moby Dick” are debates. Yet people insist on debating.

Harold Bloom has already weighed in; a few years after he made the above-quoted comment, he said this: “Stephen King is beneath the notice of any serious reader who has experienced Proust, Joyce, Henry James, Faulkner and all the other masters of the novel” (qtd. in Ciabattari, 2014). I don’t know how Bloom could have taught undergraduate English students for all those years and made this statement, but there you are. Here is another self-avowed snob, the novelist Dwight Allen: “After you’ve read Roberto Bolaño and Denis Johnson and David Foster Wallace and Thomas Pynchon… why would you return to Stephen King?” This is not the best set of examples, not the least reason being that all the writers are men, and three of them are white American men. It is also predicated upon excluding these (admittedly very impressive) writers’ worst work. Having not read enough Bolaño and Johnson, I can’t speak of their books, but after a few chapters of the expansive and frivolous Against the Day or an encounter with the aptly named Wallace narrator Ovid the Obtuse, I think most people, even serious readers, would gladly return to King, and even say that some of his writing is markedly superior.

Heck, I am willing to do both, right now.

French Dispatch Sentences. I am still looking for opening sentences with three dangling participles, two split infinitives, and nine spelling errors, in response to a challenge posed in “Fifteen-Minute Intermission”.

Below are a two marvellous submitted sentences—one by Vivian Astroff, a fourth-year student studying the History and Theory of Architecture, and one by Professor Jody Mason, of the English Department—and one sentence I’ve written.

Having put all his egs into one baskit so to speek, the show q-rated by Dudel Thomson displayed a range of werk to clearly dazzle the eye’s, to totally overcom the brain and even stimulate a debate, hanging in the new gallry; it was certainly contraversial, being a carear highlight.

V.A.

Traking Henry Jamze, after the fayled Guy Domville in London, to vividlie portray his secluzion in Rye, Jamze maykes masterpieces in Tóbín’s The Master, to carefully corral words to controll that which terrifyes.

J.M.

Broddly speeking, David Duchovny’s Fox Mulder is woden compaired to Gillian Anderson’s Dana Scully—although a Yale-educated acter and x-pected to fanatically x-cel, Mulder has a perticular yen for the cerebral monologue—and to gently put it, he overextendes and lures in the fans with his paranoia.

N.B.

Works Cited

- Ciabattari, Jane. “Is Stephen King a Great Writer?” BBC, 31 Oct. 2014.

- Dry, Judy. “Stephen King Champions It Chapter 2 Gay Character Surprise: ‘Kind of Genius.’” IndieWire, 10 Sep. 2019.

- Dwight, Allen. “My Stephen King Problem: A Snob’s Notes.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 3 Jul. 2012.

- King, Stephen. It. 1986. Scribner, 2017.

- King, Stephen. ’Salem’s Lot. 1975. Anchor Books, 2011.

- Smythe, James. “Rereading Stephen King, Chapter 21: It.” The Guardian, 28 May 2013.

February 22, 2022

Fifteen-Minute Intermission

Like ballets and operas, many long old movies have intermissions, partway through, when viewers can get another popcorn or soda, or go to the washroom, or leave gracefully. There is an intermission in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Ben-Hur (1959), Giant (1956), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and My Fair Lady (1964). Gone with the Wind (1939), which is almost four hours long (and almost four hours too long), has a twenty-minute intermission.

In this intermission, I would like to pose two challenges for my readers. Both of them come from a very literary new film, The French Dispatch (2021), which is about the composition of three articles in the life of an editor-in-chief (Bill Murray) and his literary journal—The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun—headquartered in the fictional Ennui-sur-Blasé, France, from 1925 to 1975.

The first challenge concerns a comment, made by a proofreader, about an article written by J. K. L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) about the artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro). The proofreader deadpans: “Three dangling participles, two split infinitives, and nine spelling errors in the first sentence alone” (Anderson 7). My challenge for you is to write that sentence and send it to me (noahbendzsa@cmail.carleton.ca). The best three sentences I receive will be appended to my next blog post. They need not be about the fictional Rosenthaler, but they should be in the form of the first sentence of an article about some artist or creator—writer, moviemaker, singer, songwriter, actor, painter, sculptor, showrunner—fictional or not, living or dead. For the spelling mistakes, take inspiration from the days of pre-standardized spelling (from, for instance, Spenser and Chaucer). In order to make it all hold together, you will probably need a semicolon or two.

The second challenge is to identify, or at least speculate about, what the chart drawn up by the copy editor played by Elisabeth Moss is meant to reveal about the sentence, “They will fail to notice, under the corner of a threadbare rug, the torn ticket stub for an unclaimed hat which sits alone on the upper shelf of a cloakroom in a bus depot on the outskirts of the work-a-day town where Nickerson and his accomplices were apprehended” (3–4). And what’s with that sentence? Wouldn’t “They will fail to notice, under the corner of a threadbare rug, the torn ticket stub for the unclaimed hat that sits alone on the upper shelf of a cloakroom in a bus depot…” be better, or at least more conventional?

Regardless, try not to join Joseph Grand in your compositions and speculations. Sometimes, says Nickerson, a work-a-day sentence will do.

Exeunt moviegoers.

Below are a two marvellous submitted sentences—one by Vivian Astroff, a fourth-year student studying the History and Theory of Architecture, and one by Professor Jody Mason, of the English Department—and one sentence I’ve written.

Having put all his egs into one baskit so to speek, the show q-rated by Dudel Thomson displayed a range of werk to clearly dazzle the eye’s, to totally overcom the brain and even stimulate a debate, hanging in the new gallry; it was certainly contraversial, being a carear highlight.

V.A.

Traking Henry Jamze, after the fayled Guy Domville in London, to vividlie portray his secluzion in Rye, Jamze maykes masterpieces in Tóbín’s The Master, to carefully corral words to controll that which terrifyes.

J.M

Broddly speeking, David Duchovny’s Fox Mulder is woden compaired to Gillian Anderson’s Dana Scully—although a Yale-educated acter and x-pected to fanatically x-cel, Mulder has a perticular yen for the cerebral monologue—and to gently put it, he overextendes and lures in the fans with his paranoia.

N.B.

Works Cited

- Anderson, Wes. The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun. Deadline, 2022, deadline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/The-French-Dispatch-Read-The-Screenplay.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan. 2022.

January 24, 2022

The Novelist’s Novelist, the Filmmaker’s Novelist

Here is the beginning of one of my favourite novels, Wildcat:

Late that night the boy tramped out to the old reservoir, through the Johnson’s lot with its broke glass and up the hill through the loblolly pines windwassailed at this hour, then down at the shoreline through the sedge and wholestock and whistlegrass. The night was old and hard and bright like a great glaucomic eyeball. There was an orange pickup at the far end of the lake by the trestle bridge on the gravel road to Coleman City and a man in dungarees and workboots was standing on the hasaw. The man was staring into the lake like it was some primordial well. The boy walked by pulling back at himself, and going slothly as he could came up to that hood and leaned on it and said, Hey there.

Tom Such turned and reached out his arms so suddenly like the violence before the oblivion as he took hold of and embraced the boy. You, he said. There was nothing else.

Wildcat by Eli Cash, p. 3

Wildcat was panned when it was first published, in 1998, and is now out of print. Its author, Eli Cash, reasoned that its lack of success was due to it being “written in a kind of obsolete vernacular.” Critics may have hated it, but it fascinates me. I would write a paper on it, although that could be problematic. Eli Cash isn’t a real person: he’s a character in Wes Anderson’s 2001 movie, The Royal Tenenbaums. Unlike Cash’s other novel, Old Custer, Wildcat does not even get a prop dust jacket. It is briefly mentioned, in one scene, in which a Charlie Rose stand-in brings it up and triggers Cash’s meltdown on live TV. The “excerpt” above, as you may have already guessed, was something I cooked up by doing either my worst or my best imitation of Cormac McCarthy—as Sam says, “who’s to say” (Gilman, 2012).

It’s funny, I don’t like McCarthy much. (Just now I tried reading No Country for Old Men, for inspiration writing the beginning of Wildcat, and the opening scene with Chigur and the deputy almost made me vomit.) I do, however, love movie writers. That is, not screenwriters but movie characters who are writers, especially those who have failed to live up to their potential in some way, or otherwise basked in oblivion despite their talent and the praise they so clearly deserve. There is Cash from The Royal Tenenbaums, George Gulden from One True Thing (1998), Grady Tripp from Wonder Boys (2000), Bernard Beckman from The Squid and the Whale (2005), and Joan Castleman from The Wife (2017).

Most of the films these characters appear in were adapted from novels. Two of them, One True Thing and Wonder Boys, were written by Pulitzer Prize–winners. (Anna Quindlen had already won, for commentary, when she wrote One True Thing, her first novel. Michael Chabon won for The Amazing Adventures of Cavalier and Clay, in 2001.) The Wife was first a novel by Meg Wolitzer.

I made the mistake of reading Wonder Boys and The Wife after I had seen the films. The novel The Wife, purely from the perspective of reader response, was okay. It was a little clichéd, a little heavy-handed, and the prose was sometimes awkward. But there were some good similes. (As an airplane stewardess leans over her husband, Joan Castleman remarks, “I could see the ancient mechanism of arousal start to whir like a knife sharpener inside him” [Wolitzer 2].) Chabon’s Wonder Boys, on the other hand, was a disaster—a well-written disaster, but a disaster nonetheless. The novel’s Grady Tripp is insufferable—the first insufferable literary pothead I have ever encountered—and not in the least engaging, empathetic, or otherwise worth reading about. I would quote from the novel, but once I was finished with it, I got rid of it as fast as I could. The only thing I got out of its three-hundred-odd pages was that Michael Douglas, who played Tripp in the movie, is a magician, transforming an annoying lecher into an earnest, likeable muddler.

I have a general theory about why it’s more fun to watch these characters than to read about them. It’s because you’d rather be reading what the characters themselves have written. Successful metafictionalists, like Philip Roth, know the perils of making their novelist characters’ novels more interesting than their own. When Roth writes about Philip Roth or Nathan Zuckerman, he has them tell the story he wants them to tell, the interesting story, rather than merely alluding to how these characters once won the PEN Award or the National Book Award or the “Helsinki Prize.” Nobody, least of all me, wants to read about how a character is in a slump because they’re typing away on an endless project, or because they’re always stoned, or because they didn’t get tenure at Harvard one time. And in print, there’s only so much you can do with a blocked writer. Although Roth and Zuckerman often agonize over whether they have gotten the story straight, at least they give it a shot.

But this is a negative theorization. It doesn’t answer why watching these writers on film isn’t tedious. For me, the answer is simple. I like watching movies and TV shows on their own terms. Watching them rarely inspires me to read about their characters’ interests. (Besides, films are rarely really about what their characters are interested in. The Sweet Smell of Success [1957] isn’t about newspaper culture but power; The Draughtsman’s Contract [1985] not about drafting but semiotics; Goodwill Hunting [1997] not about “math” but something else, I assume. I don’t know.)

The more interesting question is why I like the writer movie-character in the first place. Why do I think that Eli Cash and Grady Tripp would be great professors, when there’s sound evidence they wouldn’t be? (When would they even have time to mark midterms?) Why is Bernard Beckman fascinating even though he’s a jerk? Why do I want so desperately to read The Walnut, even if Joe Castleman’s name were on the cover instead of Joan’s? Why is George Gulden my hero? I don’t intend to answer all of these questions. Some of them come down to taste and thus aren’t very interesting for anyone other than myself. Cash is charming and silly and easily hurt. His vulnerability is cute. Tripp, (un)blocked as he is, has a debut novel whose name, The Arsonist’s Daughter, is right out of Harold Brodkey’s top desk drawer. Beckman (Jeff Daniels) is a petty narcissist, but I can stomach watching him blunder through his personal life, because I’ve known men like him, and he’s hardly an exaggeration. Now, my loves of George Gulden (William Hurt) and of Joan Castleman (Glenn Close and Annie Starke) are a little more complicated and deserve more detailed explanations, because I think these loves are revealing.

In addition to being white, straight, and male, Gulden shares a lot of traits with Cash, Tripp, and Beckman. All four of them teach at insignificant, fictional liberal arts colleges. Like Tripp, Gulden has run up against the old 8×11 white wall in his writing life; like Beckman, he’s an unrepentant narcissist (at least, up until the end); and like Cash and Tripp, he’s an addict. Cash, Tripp, and Beckman, though, are all meant to take up space in their respective pictures. Tripp and Beckman are the main characters of Wonder Boys and The Squid and the Whale, respectively, and Cash plays the pivotal role in The Royal Tenenbaum’s zany climax. Gulden is not supposed to be the focus of One True Thing. He is meant to shadow the beginning of the film as an august presence, only to be defoliated as the film progresses and his daughter, Ellen Gulden (Renée Zellweger), realizes how shallow and self-centred her father really is, shifting her allegiances from him to her dying mother (Meryl Streep).

I have watched One True Thing perhaps three times now, twice all the way through. George never loses his centrality. His literary anecdotes are all the same, customary tchotchkes of Mr. American Literature. Something-something Gertrude Stein, punchline Hemingway. So-and-so kept rotting fruit in their desk to boost their concentration, so now I keep rotting fruit in my desk. He tells his daughter her prose needs to be “more muscular,” and then goes on to say, “When I was twenty and working at The New Yorker, I would spend a whole day working on a single sentence” (Hurt, 1998).

Now, you might think you’ve got me. Didn’t I just spend my last blog going on and on about The New Yorker? Isn’t that what English students do, talk about The New Yorker until they’re either working there (unlikely) or dead? This is true, but I assure you, it isn’t why I’m interested in George. When I first saw Knives Out (2019) and Daniel Craig’s character says that no one reads Gravity’s Rainbow, I leaped out of my theatre seat. “I did! I did!” I may have screamed, in that blank moment in which I lost all self-control—but Knives Out is not a movie that I have returned to or that I have any yen to return to any time soon. Moreover, George’s “more muscular” comment is vague and airy, and his New Yorker name-drop is pathetic and, perhaps unintentionally, hilarious. So Ellen’s prose is supposed to be more muscular… like Cormac McCarthy’s? Roger Ebert points out that if George really did spend all day on a single sentence, “then to meet his deadlines he must have had to dash off his other sentences in heedless haste” (par. 3). In this case, as welcome as literary references usually are in the movies, George is not exactly paying good writing a compliment, or arguing for his presence continuing to overshadow the clichéd, albeit well-acted, mother-has-cancer storyline.

My love of George is an extra-textual imaginative process. It isn’t something that the movie means to happen; it just happened to me. I see what kind of academic and writer the character could have been, and in this role, he is oddly inspiring. My own failures as a writer and tyro scholar can crouch behind his image. The character George is at once a literary hero, incapable of letting me down by virtue of his fictionality, and a disguise. He is a set of Groucho glasses that I can pull on when I am writing something difficult. (Like you, I have other disguises, too, but they are completely of my own design.)

Joan Castleman, on the other hand, does not represent a disguise; she is the locus of all the technique of which I am arrogant, the technique that darts a yard or two ahead of my laziness. Not once in the film The Wife (as is the case with George) are readers privy to any of Joan’s prose. Instead, we are merely tantalized by how she writes. In one scene, she explains to her husband, Joe—for whom, like Colette, she is ghostwriting—why a scene of a woman folding laundry goes on for so long (he feels it should be cut). It’s not about the laundry, she says, it emphasizes the woman’s loneliness, her sense of waiting. What would this look like on the page? Would the reader be able to grasp this, or is it too subtle? It doesn’t matter: the challenge has been set, the paces walked. I get the feeling someone has done it, even if, on second consideration, they really haven’t.

The other thing that I long for and envy about Joan’s writing life is its sense of stability. Her husband has his names on her books, but her life is taken care of. She gets none of the credit, but she is allowed to write, to communicate her ideas through stories that are ostensibly Joe’s. For her, the work is a form of therapy from the badness of her marriage. She feels misused: Joe has his affairs, is hailed as a literary genius; she is the invisible woman. Her presence, dependence, and servitude are expected. As a person, however, she is no more than “the wife.” I am not a woman and did not live through the 1960s as a housewife and homemaker, so I cannot say for certain that I would feel any less resentment than Joan does, placed in her situation. But I do think I would be amenable to it. My temperament is more in line with Alma’s (Vicky Krieps) in The Phantom Thread (2017): I am ultimately a codependent person. I need a sense of home and being a spouse or partner (in both the romantic and productive sense; children are optional).

This is somewhat the same feeling I have for Alice Munro’s life. Despite everything she has had to endure—depression, sadness, loss, anger—there is something enviable about her life seen from the outside. I suspect Meg Wolitzer feels somewhat the same way about Munro. She has Joan refer to the ability of “the gelatin of art [to] contain and suspend” life (165), and for those who have read the short story “Material,” it’s hard to see “the gelatin of art” as anything but a reference to that famous “marvellous clear jelly” (Munro 43). So it isn’t surprising that Joan’s life is an intensification of the feeling I derive from Munro’s. And the film, in clarifying the relationship between the fictional writer and the real one (it changes the “Helsinki Prize” to the Nobel Prize, which Munro won in 2013), only makes Joan’s life even more tangible.

What I like about both Joan and George is that they allow me to transport myself out of the life I am currently living. (I feel as though I have read this somewhere before.…) This is one of the functions of good fiction. When it comes down to it, Joan and George are the kernels of stories I tell myself about writing and stories that allow me to write. They are enviable, inspiring, other lives. They are a few movements and sounds into which I am helpless but to see myself, just as I am often wont to do with prose:

The dryer made a flat, congested sound, like a rubber bicycle horn. Maeve checked on the sheets, but they were still damp, and she put them on again. When she returned to their bedroom, she saw at the foot of the bed the pile of clothing. She had pictured herself and Thom, too absorbed in themselves, bypassing it for the bed, when she had dumped it there from where it had sat, since Friday, in the middle of the mattress. And perhaps he wouldn’t notice; it was not for noticing. But she saw it now. Were he here, her husband would stare, grunt. Perhaps, in the right circumstances, he would even stoop, pick it up, and deposit it on the dresser. There it might look as though as though it were part of a process interrupted, that she had momentarily stepped away and might resume at any time. It had been on the bed since Friday. Now it was Sunday. She began to fold it, one piece at a time, leaving the unfolded clothes on the floor and piling the folded ones on the dresser. She bent and righted, bent and righted at the waist like a wooden doll. Took two steps across the room to the dresser. At first, she only folded his clothes. Even his sweaters, now creased, which she needed only hang up. Then, when she had finished, she made a separate folded pile of her clothes on the dresser. The pile on the floor was gone. She checked the dryer: the sheets were still damp. It was after six o’clock, and the afternoon light was gone.

The Walnut by Joe Castleman, p. 58-59

Works Cited

- Cash, Eli. Wildcat. New York: Brooks UP, 1998.

- Castleman, Joe. The Walnut. New York: Pantheon, 1961.

- Ebert, Roger. “One True Thing.” Chicago Sun-Times, 18 Sept. 1998. RogerEbert.com, www.rogerebert.com/reviews/one-true-thing-1998. Accessed 26 Nov. 2021.

- Gilman, Jared, performer. Moonrise Kingdom. Directed by Wes Anderson, Indian Paintbrush and American Imperial Pictures, 2012.

- Hurt, William, performer. One True Thing. Directed by Carl Franklin, Universal Pictures, 1998.

- Munro, Alice. “Material.” Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You, 1974, Penguin, 1990, pp. 24-44.

- “Three Plays.” The Royal Tenenbaums, directed by Wes Anderson, Touchstone Pictures and American Empirical Pictures, 2001.

- Wolitzer, Meg. The Wife. 2003. Pocket Books, 2018.

November 11, 2021

Reading Copy

Would you believe… that I actually exclaimed “Ah-ha!” when I thought that I’d spotted an error in The New Yorker? I was out in public, and I’m sure my reaction would have drawn looks, if I hadn’t been in a parked car in an LCBO parking lot. (I was waiting for a friend.) The apparently offending sentence appeared in “Legitimation Crisis,” by Louis Menand, and was published in the August 16, 2021, issue. It ran: “In 1966, Congress passed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, which empowered the federal government to set safety standards for automobiles, a matter heretofore left largely to the states” (Menand, “Legitimation” 71).

Do you see it? Don’t squint too hard; you won’t find fault with the punctuation, and there is no egregious but invisible homophonic misspelling like “no-nothingism” (see Lizza 45). The problem, I felt, was the word “heretofore.” The article was not published, in 1966, just after the passage of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. My understanding, backed up by the Oxford English Dictionary, was that “heretofore” meant “before now” or “up until this point.” As I understood it, it did not mean “up until that point”—which is what Menand means.

If you have ever stopped reading right in the middle of a novel’s action sequence to ponder a word’s proper or improper usage; if you have ever paused mid-essay because of a superfluous or, more often, missing comma; if you have ever.…Well, I had to crawl through the first pages of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, because I kept getting stopped where my 2015 edition renders “co-workers”as “coworkers.” This is what grammar and usage are like for some of us (and maybe for you, too). They have a great capacity to get us riled up.

As it turns out, I hadn’t spotted a mistake in Menand’s work. When I got home, I realized that The New Yorker uses Merriam-Webster’s dictionaries (Norris 18), because of course they do. Oxford has been known, in the past, to merely refer readers to Webster’s (see Hyman 11031) and, as Webster’s itself notes, is in part responsible for the widespread, erroneous claim that Shakespeare coined x words, where x is equal to 1,700 or greater. Webster’s, on the other hand, tends to do the lexical heavy lifting. They are the champions of usage, telling us that, yes, “funner,” “conversate,” and “irregardless” are indeed words, and you can go right ahead and use them—at least, in casual settings. In their on-line dictionary, they define “heretofore” as a synonym of “hitherto,” which even Oxford defines as “until now or until the point in time under discussion” (my emphasis). Menand means “heretofore” in the sense of “hitherto.”

It would have been highly ironic if I had spotted an error in Menand’s article. It was he, more than anyone else, who first turned me on to grammar and usage. In ninth grade, when I was thirteen, I still had little notion of what a verb, noun, or adjective was—let alone what constituted a sentence or how to properly use a comma. In an attempt to better myself and my writing, I started reading Eats, Shoots & Leaves, by Lynne Truss. After getting a few pages in, not realizing that it was not a grammar and usage guide but a comedy book, I was puzzled. Even as a punctuator-by-ear, I could tell that there were many more solecisms than there ought to have been merely by chance or human error. This was a book whose title referenced a joke about the ambiguity generated by misplaced commas, and yet, in the text, there were missing and misplaced commas everywhere. Where were the copy editors? In my own naïve way, I was apoplectic: I had wanted to learn something and instead was, as I read, merely tallying vague grievances of my own.

As teenagers do, I turned to the Internet for someone who shared my opinion, for an expert who could precisely diagnose what was wrong, and validate what I felt. That expert was Menand. His 2004 review of the book, titled “Bad Comma,” begins, “The first punctuation mistake in ‘Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation’… appears in the dedication, where a non-restrictive clause is not preceded by a comma. It is a wild ride downhill from there” (Menand 102). I’ve read “Bad Comma” in its entirety maybe six or seven times, parts of it upward of a dozen; I have never made it past chapter two of Eats, Shoots & Leaves.

None of this is to say that I am now, or ever was, a stickler—that is, someone like Truss’s popular image. Truss’s narratorial voice is a part of a pervasive stereotype (maybe less pervasive in English studies) that says those who care deeply about language and grammar—just as much as they do about the meaning that words and punctuation together are trying to unambiguously convey—are uptight and have the irrepressible urge to correct any and all violations of language conventions. I think this originates, for most people, in primary school and older, prescriptivist systems of education, where teachers were intransigent when it came to anything but a very narrow range of usage. These people, Lynne Truss sticklers, hiss and recoil when someone uses so-called adman slang, like “accessorize” or “prioritize”; or uses “impact” or “loan” as a verb; or ends a sentence with a preposition. Assuredly, these people will have stopped reading this by now, because I have already split at least two infinitives in this post, one in this paragraph.

My anger at the mistakes in Truss’s books was the same kind of anger that she says she feels at the sight of a grocer’s apostrophe (mistakenly pluralizing a word by adding an ’s). But—and this is important—it was born out of disappointment and not out of fear or resentment; a book I believed capable of helping me, let me down. I don’t maliciously correct people’s usage in conversation, and I don’t think there’s any real need to correct minor errors in print. (Yes, it annoys me when a certain scholar writing on We Need New Names spells “Bulawayo” three different ways, but my thinking is, “As long as the scholarship is good…”) People make mistakes, and doubtless at least one grammar or usage error has slipped past me and my editor (more likely me) in the course of writing this very article.

I very often, in fact, try to pay less attention to rigid punctuation and grammar conventions, not that I have ever done this with any particular degree of success. I often wish I could write a little more like Styron, whose sense of restrictiveness is refreshingly broad. Sophie’s Choice begins with an omitted comma after an introductory clause (“In those days cheap apartments were almost impossible to find in Manhattan” [3]), and it just gets better from there. I’ve also come to really like the convention up until the middle of the twentieth century of putting semicolons between complete clauses and coördinating conjunctions preceding complete clauses. It can give a sentence a wired, pugilistic spirit, even if Henry James is the one doing it (“I slept little that night—I was too much excited; and this astonished me, too” [18]). And what about the British convention—bad form in the United States and much of Canada—of putting punctuation, like full stops and commas, outside quotation marks? Toril Moi does this so assertively that I was once helpless to not to do the same, after reading her.

Of course, there are also those writers whom none of us want to emulate. But their writing, hapless as it is, can be a lot of fun, too. That is, it can be funny, funny-ironic. This is especially true since the work is largely unimportant, the writer usually remains anonymous, and no one feels like they’re the direct butt of the joke. In other words, no one gets hurt. Grocer’s apostrophes, which are ubiquitous, are quaint but not funny; you almost feel that conventions will change to accommodate them, and someday soon. I’m referring to bigger things, ontological things. These sorts of things concern real grocery stores.

When I was working at Loblaws, the summer of 2019, there was a sign in the lunchroom that read: “WARNING: We regret that this is not an allergy free room.” As I didn’t care much for the building, I might have been using peanut butter after all. Many older Loblaws locations also have an ersatz Eastern European deli, complete with a red false awning. Under each awning is a sign that reads: “La Marchetta.” You might innocently think that this is Italian for “the market”—whoever commissioned those signs certainly did. Actually, it means “hustler” or “prostitute.” (The deli pictured doubles down, and a sign, on the left hand side of the frame, declares that it is located at “104 Marchetta Avenue.”) Who knew our grocery stores were living such full lives.

Compared to these—what are they, faux pas? snafus?—a lot of the grammar and language ambiguities on the Internet are relatively tame. However, I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity to point out a similar transfiguration that I’ve noticed on-line, with the proliferation of writers referring to themselves as “dog mom”s or “dog dad”s. I guess it’s only to be expected; after all, at one point there were an awful lot of “dog lovers” in cyberspace. I wonder what Menand would say about that.

Works Cited

- Hyman, R. “Parapsychology.” International Encyclopaedia of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 2001, pp. 11031–35.

- James, Henry. The Turn of the Screw. 1898. Arcturus, 2019.

- Lizza, Ryan. “The Duel.” The New Yorker, 1 Feb. 2016, pp. 38–45.

- Menand, Louis. “Bad Comma.” The New Yorker, 28 June 2004, pp. 102–04.

- —. “Legitimation Crisis.” The New Yorker, 16 Aug. 2021, pp. 70–73.

- Norris, Mary. Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen. 2015. Norton, 2016.

- Styron, William. Sophie’s Choice. 1979. Vintage International, 1992.

September 15, 2021

An Introduction

I am supposed to introduce myself. I am not Jaclyn Legge and, therefore, am someone else, something different. At first, I toyed very briefly with the idea of emulating Anne Carson: “Noah Bendzsa was born in Canada and does not know ancient Greek.” It’s playful but hardly sufficient. Even Carson has had more written about her than that.

In drafts two through five, I entertained a different idea. I might avoid introducing myself altogether, assume my being, and begin in medias res. I began to write—unsystematically, compulsively—about two subjects that had been on my mind for some time: Evan Rachel Wood’s presence in Green Day’s prefab music video “Wake Me Up When September Ends” and Emily Ruskovich’s takeaways from the “The Love of a Good Woman.” I did not get far writing about either of those things. My last attempt at this kind of writing was to try to interpret a cryptic Don DeLillo quotation from Underworld, which I believed would illuminate my need to write about such disparate subjects. As it turns out, I misremembered the passage; I believed it to be about the duty and impulse to record, but it is actually about satisfying memories of “old times,” especially those shared with erstwhile lovers (DeLillo 64). Far too personal—that was certainly not what I wanted to write about.

I have never been able to comfortably speak or write about myself. Do not think that it is out of any misguided sense of duty to politeness. It is partly because I am a private person, partly because I see writing about the self as a largely futile task. (I will this from an expression of pessimism into one of realism.) In addition to a confused experiment in biochemistry, we are constructions of our stories and the stories others tell about us. The issue is that the only lens we have to view ourselves is warped, and so these stories and our identities are unstable.

I often default to throwing up my own identity on the foundations of the most dramatic stories in my repertoire. I couldn’t stand being an unreflective bore, and I find these stories are the most engaging for listeners. Here are a few. When I was eight, while spelunking, I punctured the skin of the back of my head. It bled profusely, and I thought I was going to die. (I was a romantic and theatrical child.) When I was twelve, I broke my arm in rural northern Ontario. It took ninety minutes to get to the hospital, over poorly paved roads. The relatives I was staying with were as distressed as I have ever seen them, which I am sorry for, as the accident was my fault. My normally tough-love grandfather read aloud to me from Rum Punch, while I was laid up in the E.R., waiting for my radius and ulna to be manipulated back into place. When I was seventeen, I gave the first half of my valedictory speech in character as Groucho Marx. “Let me unzip my sweatsuit,” I said of my gown. My speech advisor, who didn’t know what I was going to do, got up and threw his back out. (He alleges this was unrelated.) My peers, not up on their vaudeville and nineteen-aughts to -forties humour, were baffled.

These stories, the sketches of them I have pencilled, jump through the years of my life because it has been largely unextraordinary—or no more extraordinary than anyone else’s. But, far from complaining, I enjoy the ordinariness of my life. Dramatic stories of high jinks and disaster may be entertaining for casual listeners, but they are ultimately guests who overstay their welcome and leave rings on the coffee table. I most enjoy plain stories concerning small, everyday occurrences and observations. Going to buy groceries; a bus ride to physiotherapy; something heard on the radio or learned on the Web; common, irrational fears of failure and exposure. These personal stories are the most intriguing and multifarious, and best reveal a person’s ostensible character and—dare I write it?—“the nature of the human condition.”

Much of literary and visual art is populated by the small observation or seemingly meaningless incident. The recently reappraised John Williams novel Stoner (one of my favourites) is predominantly a collection of small incidents, the play of light and shadow, in the life of its protagonist, an early-twentieth-century Missourian college professor. A large part of why Alice Munro, whose work is the subject of my undergraduate thesis, is such a tremendous writer is because she is able to so perfectly capture little details, like the feeling of lightness when wearing “rubbers” after a winter of boots (Dance 120). But, despite an early Munro surrogate’s desire to record “every last thing, every layer of speech and thought, stroke of light on bark or walls, every smell, pothole, pain, crack, delusion” (Lives 201), I think Mary Pratt, the Nova Scotian photorealist, can at times be an even better observer of the everyday. Of her 1969 painting Baked Apples on Tin Foil, she says, “These apples are almost jewels, set in silver, gold, amber, and yet are obviously mundane, arranged in rows for ‘proper heat distribution,’ on tin foil for ‘easy clean up,’ redolent with cinnamon and cloves. They refuse to be boring—flaunting their romance despite every effort on my part to tear them from their history and their legends. They cry to be celebrated” (qtd. in Gwyn and Moray 42).

The memories that currently “cry to be celebrated” in my own life are those of my cousin Cary and my brother, Zooey. (I have changed their names.) I have been thinking about Cary for fairly obvious reasons. He and I spent some time alone together this summer, when he drove down for the weekend to where we were staying, in Coldwell, Ontario. I don’t drive, so he took me into the nearest town, one day, and we went shopping. Another day, we biked side-by-side to a café, on a wide dirt path that connects the settlements adjoining Coldwell. With most of my worries and anxiety deferred, surrounded by the pacifying bucolic landscape of southern Ontario, I wondered what in life could be better and felt immediately nostalgic for the moment I was in, and wanted to live there. Cary was part of that.

Why I think of Zooey now is a little different from why I think of Cary. Since he was born, this is the first year of my life that I will be without my brother. (He is now a freshman, living in residence, at an east-coast liberal arts college.) Even Cary’s image, built over precious few visits since the mid twenty-teens, has only a few discontinuities—since when has he been old enough to drink?—and gives the illusion of stasis. Zooey is harder to see, since he has been here every day for these past eighteen years. The changes in his character, despite their importance, appear minute and may only be glimpsed peripherally. His abiding image hung over the centre of my eye like a cataract, and now it is gone. His absence has forced my vision to the sharp edges of this newly clear space.

As a child, Zooey was strong, compact, and unflaggingly optimistic. His nickname was Serg, an abbreviation of “sergeant.” He was always the biggest kid in his grade, had a barrelling walk, and wanted to impress his own kind of seriousness on everyone, even adults. None of this has really stopped being true; it has only been let down, like rolled cuffs, as he has grown older.

When he was eleven or so, Zooey began playing a competitive sport—I’ll say tchoukball—to great success. (He is now playing for his college’s varsity team.) He went to tournaments in Hamilton, London, Toronto, and I began to see less of him. The past few years, much of his free time has been spent in the gym or on the track. I’ve been so proud of him for so long that it feels like a hopeless task to try to adequately express my pride. When my friend Beatrice would ask how I was, in high school, I would invariably tell her about how tall my brother had gotten and how he was playing on three different tchoukball teams and how he was scoring n number of points a game. With him, though, I almost felt that I needed to downplay the importance of his accomplishments to me. I would make statements like “the world doesn’t revolve around tchoukball” and reproach him for his monologues—while mine were always far longer and more self-indulgent—about the style of play of his tchoukball heroes. I regret my inarticulateness and my buried sentiments, but it doesn’t and didn’t seem like there was a lot else that was open to me, as an older sibling: this was how we talked.

One of the best things to come out of being stuck at home for so many months was that, with gymnasiums closures, Zooey and I got to spend more time together. Summer afternoons, we would watch our favourite soap operas. We lay on oversized, under-stuffed pillows in my rented room in Coldwell, watching on my computer screen. As we rooted for the American patriarch to show up the officious Europeans, the vagarious blonde to get a grip and make up her mind—the Swede or the Louisianan—Zooey would hoot, grin, and talk at the characters. When he spoke, it was an eruption of the half-abashed sweet talk of television viewership. Where had he learned?

Another time, when my magazine subscription accidentally removed me from their mailing list and stopped sending me new issues, we walked the five-mile round trip to our local bookstore, to try and get the one that they had failed to send. (From that perspective, it was a fruitless endeavour—the bookstore only gets the magazines in a week after they are sent out to subscribers.) I don’t think we talked about anything very important, just how fast we were walking and the distance to the store, something about how he was feeling about going away. It was such a beautiful, warm day. Zooey holds his chin too high, as though he needs be any taller, and still has the vestiges of that barrelling walk he developed as toddler. Despite his sportiness, he never fulfilled the negative stereotype of an athlete, and has always been an incredibly kind, gentle, and self-sacrificing person. He makes me feel safe.

In the end, I have neither introduced myself (I was born in Ottawa, in 2000. I grew up in Riverside Park and wished it were elsewhere) nor begun with a dis-authored torrent of words. Instead I’ve written about two people who are close to my heart, whom I have felt compelled to write about. And for this reason I’m not sure this post has gone anywhere for anyone aside from myself. It’s my hope, though, that anyone who has read this can see some small measure of themselves, their own ordinary stories, in my life—no matter how different our lives might be—and find comfort in that, or else take the time to examine and enjoy their own memories of people whom they love.

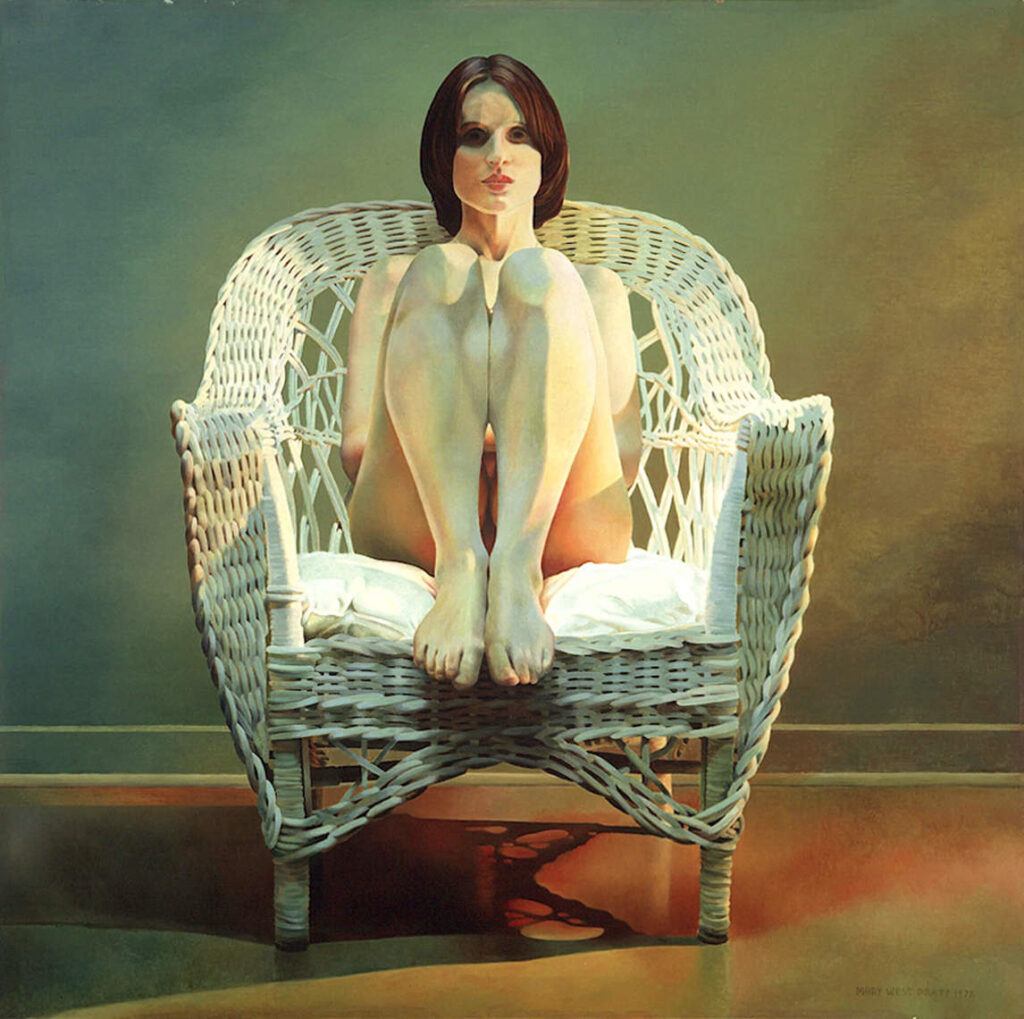

Although Munro is often accused of burying pieces of herself and people she knows in her work, it is again Pratt who grabs the ring, for she assuredly does. I can’t think of a more radical, innocuous, accusatory painting than Girl in a Wicker Chair (1978). It is Mary looking at Donna Meaney looking at Christopher Pratt looking at us, all in a single gaze. And aren’t we meant to see in that simple look the whole of those relationships?

Works Cited

- DeLillo, Don. Underworld. Scribner, 1997.

- Gwyn, Sandra and Gerta Moray. Mary Pratt. McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1989.

- Munro, Alice. Dance of the Happy Shades. 1968. Vintage, 1998.

- —. The Lives of Girls and Women. 1971. Signet, 1974.