The Social Economy of Food:

Informal, under-recognized contributions to

community prosperity and resilience

Critics of neoliberalism argue that people are better conceived of not as self-interested, profit-seeking, utility-maximizing creatures, but rather as members of complex social and ecological systems, whose choices are deeply embedded in social relationships and ecological context (Bourdieu 1998, Ophuls 2000, Siebenhüner 2000, Patel 2009). Recent work on the concept of a social economy focuses on enterprises that foreground social and environmental values yet still recognize the importance of economic viability. While research suggests that such enterprises may be sites of significant innovation and creativity (Leyshon et al. 2003, Gibson-Graham 2006, Downing, 2012), work to date has focused heavily on cooperatives and social enterprises, with significantly less attention paid to activities that are less formally structured.

While the concepts of a social economy and an informal one have traditionally been regarded as separate areas of research, findings from a number of Canadian studies indicate significant overlap between the two (Teitelbaum & Beckley, 2006, Thomson & Emmanuel, 2012, Knezevic, 2015). First, both share an emphasis on personal relationships, trust, and non-market values, which are inherently challenging to define and often impossible to quantify. Second, both offer spaces for non-traditional forms of innovation as well as opportunities for deep insights into social relationships, cultural meanings, and environmental values. Most importantly, both challenge us to think of economic systems in far more complex ways than mainstream economic theory would propose (Ostrom, 2010).

Project at a Glance

We have used case studies to identify and document a spectrum of multifunctional social economy food activities where people trade/share material resources and skills at times in informal ways. The case studies and interviews have been grounded in Community Based Research (CBR) as a way to develop a clearer sense of issues facing the groups, and dig into specific challenges as identified by community partners. Working within groups over an extended time has allowed a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities, which we are exploring through ongoing engagement.

See below for case studies and links to a video series on the social economy of food.

References are available at the bottom of this page.

Case Studies

Subversions from the Informal and Social Economy

The case studies from the Social and Informal Economy of Food research series highlight almost a dozen community initiatives from across Canada; from Hidden Harvest, a for-profit social enterprise located in the Nation’s Capital that supports the practice of harvesting fruits and nuts in urban areas to the vibrant seed saving community in Atlantic Canada.

The Social and Informal Economies of Food research series also includes a cluster of case studies focusing specifically on Northwestern Ontario and the diversity of approaches in building a social economy. These three case studies reveal the breadth of the meaning of social economy in increasing prosperity for marginalized groups; building adaptive capacity to increase community resilience; bridging divides between elite consumers of alternative food products and more marginalized groups; increasing social capital; and fostering social innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic diversification.

These case studies and the invaluable contribution of their work were made possible through generous funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Case studies

Understanding the Role of Environmental Sustainability in a Social Economy of Food: A case study of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in Ontario.

M.A. Lemay, June 2019.

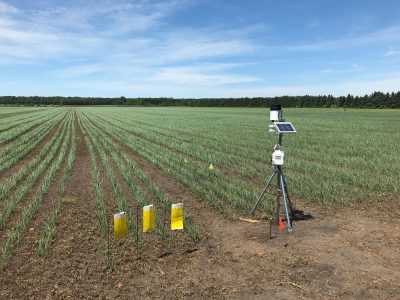

Yellow sticky traps and weather station on an onion field in Holland Marsh, Ontario. Source: T. Cranmer, OMAFRA.

Project Overview: This case study explores how integrated pest management (IPM) might fit within and serve a social economy of food paradigm that envisions a more sustainable (social, ecological and economic) food system. It adopts an exploratory approach using documentary and digital sources of data and personal communications with IPM crop specialists from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), several provincial commodity organizations and independent IPM consultants to describe the different models for and means by which IPM is designed, delivered and practiced across the Ontario agri-food industry.

The analysis provides evidence of how IPM contributes to ways of overcoming some of the barriers to sustainable food production and food security inherent in conventional agricultural production. It demonstrates how IPM is a promising approach by which alternative food production systems can work towards ecological resilience and how it advances a social economy of food paradigm.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

Black Duck Wild Rice—Powerful New Case Study

Paula Anderson, based on participant observation and interview with James Whetung, August 2018.

Contested Wild Rice Beds on Pigeon Lake. Source: Larry Wood.

Project Overview: In this case study, Paula Anderson and James Whetung explore the transformation of Black Duck Wild Rice (BDWR) from a small, private, for-profit business to a multi-faceted, community-integrated social enterprise sharing seed knowledge and an element of control through community seeding, harvesting and processing of natural food resources.

The case study takes you through the historical, geographic and social context of BDWR, and lays out all of the resources that have contributed to the development of this labour of love.

“…the answer needs to be more active. Reconciliation needs to be a process. Nishnaabe people have shared, to the point that they are doing without the basic necessities, such as healthy traditional foods and the means to access them within their own traditional territories. So there has to be a re-sharing, sharing right from the top to the bottom. This is the process of reconciliation.”

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

Hidden Harvest Ottawa

Chloé Poitevin DesRivières, based on participant observation and interviews with the founders of Hidden Harvest Ottawa Jason Garlourgh and Katrina Siks, March 2018.

A Hidden Harvest sign. Source: Chloé Poitevin DesRivières.

Project Overview: This case study from the Social Economy of Food research series focuses on Hidden Harvest, a for-profit social enterprise based in the Ottawa Valley. Hidden Harvest rescues fruits and nuts from trees located on private and public lands and aims to create a self-sustaining business model to build public capacity and knowledge to access fresh, healthful food in their own neighborhoods.

Co-founders Jay Garlough and Katrina Siks partnered in 2011 to act upon their concern over the large amounts of unused food produced by trees and vines in the City of Ottawa. While people have unofficially collected fruits from trees on private and public lands in the area, the co-founders wanted to legitimize, formalize and popularize the practice. Upon realizing that no organization existed with the sole purpose of rescuing nuts and fruits in Ottawa, Garlough and Siks put their plan for Hidden Harvest into action, securing local partners and funding. In 2012, the first official harvest took place, and there have been approximately 387 harvest events as of January 2017.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

DIG (Durham Integrated Growers for a Sustainable Community)

Mary Anne Martin, based on participant observation and overviews with Mary Drummond, Jasmine MacDuff, Cesar Caneo, and Sherry Macdonald, Autumn, 2016.

Project Overview: This case study from the Social Economy of Food research series highlights DIG (Durham Integrated Growers for a Sustainable Community). Compiled by Mary Anne Martin, the material for this case study was collected through interviews with the president of DIG, the coordinator of one of its member projects and one organization that has benefitted from regular delivery of produce from a member garden. In addition, it draws on documents and observations from: DIG’s website, its member projects, its annual general meeting, an executive meeting and a meeting of the Durham Food Policy Council (of which DIG is a member). As a participatory action research initiative, this research involved a collaborative project with DIG and the Durham Food Policy Council that analysed municipal policy in Durham Region to assess its support for urban agriculture and food security. The findings from the policy research also informs this report.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

The Guelph Centre for Urban Organic Farming

Megan Thomas, based on participant observation and interviews with Martha Gay Scroggins, Martin Ronda, and Patrick Kelly, with editorial support from Erin Nelson and Karen Landman, August 2015.

A selection of Guelph Centre for Urban Organic Farming’s harvest. Source: GCUOF Photo Gallery.

Project Overview: The Guelph Centre for Urban Organic Farming (GCUOF) is a certified organic farm at The Arboretum, University of Guelph, which is focused on teaching sustainable urban practices in food production and acting as a living laboratory for departmental research. The University of Guelph was the first school in North America to have an Organic Agriculture major, and is unique in offering both applied on-site learning in addition to conventional academic learning (Jalal, 2010).

Since it’s development in 2008, this centre has become a field classroom for students from the Ontario Agriculture College and other disciplines. It is a place where one can learn about sustainable food production, permaculture, heritage seed production, and food security (University of Guelph, 2015). While GCUOF’s primary purpose is to be a learning and research platform, its involvement and outreach in the community has numerous added benefits. The farm relies heavily on volunteer involvement and much of the success of the farm would not be possible without outside help. GCUOF inspires conservation about sustainable agriculture, provides satisfaction in knowing where one’s food comes from, and prepares us for a different future.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

The Ontario East Alternative Land Use Services (ALUS) Program

Compiled by Lauren Allen, based on participant observation and interviews with Bryan Gilvesy, Brendan Jacobs, and Jacqueline Pemberton, August 2015.

Buffer zone after vegetation has become established. Source: Ontario East ALUS.

Project Overview: Alternative Land Use Services (ALUS) is a non-profit program offering an innovative model for environmental conservation, by providing farmers with financial incentives for the ecological goods and services produced on their land. ALUS pays farmers to retire land from agricultural production, and retain or convert it to a natural state, such as a grassland, wetland, or riparian buffer.

In 2012, ALUS launched a pilot program in Eastern Ontario, with the aim of implementing between three and six projects over the course of the three-year pilot. In 2015, as the pilot project drew to a close, it had far exceeded its original goal, with twenty-one projects implemented on fourteen separate farms.

While ALUS is an environmental program, it also has important economic and social benefits. By assigning an economic value to ecological goods and services produced on farms, the program helps to fill a gap in the Canadian economy. The program also helps to build ecological and economic resilience in communities, while building networks and bridging divides among individuals and organizations from a variety of sectors. These qualities help contribute to both increased food security and community development.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

Seed Saving in Atlantic Canada

Norma Jean Worden-Rogers, December 2015.

Pea plants at Sackville Community Garden. Source: Worden-Rogers

Project Overview: Seed saving is an important process that is integral to food security. With climate change altering the longstanding conditions that growers have come to expect, the need for location-specific seed can be a solution to this problem. Harvesting seed that has adapted to local conditions has many benefits ranging from saving money, to increasing local resilience, to ensuring that the crops have adapted to specific growing conditions. This is necessary in a time where large seed companies are creating ‘Swiss-army-knife’ varieties that are marketed as ‘well-rounded’ and ‘adaptable’, but do not flourish in any specific condition therefore often resulting in smaller yields.

This case study explores the relationships that are necessary to create a vibrant seed saving community in the Atlantic Canadian provinces. Due to the small population size of the region, relationships are crucial for the knowledge transfer, support, and resources required to increase food security. Interviews with partners in the non-profit, institutional, and individual sectors exhibit the significance that collaboration has played in their contribution to seed security. Whether in the form of grant collaboration or resource sharing, these sectors have benefitted from the support system that has been created in Atlantic Canada to make the region more resilient, and ultimately increase prosperity.

“Every seed is the family bible and history of the history of the plant – the amount of information that’s packaged in a single seed is extremely significant.”

Will Bonsall, The Scatterseed Project

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

Blueberry Foraging as a Social Economy in Northern Ontario

William Stolz, Charles Z. Levkoe and Connie Nelson, September 2017.

Wild blueberries. Source: Stolz, Levkoe & Nelson.

Project Overview: As one of the case studies that focus specifically on the social economy in Northwestern Ontario, this project examines four blueberry foraging initiatives in Northwestern Ontario to show how foraging for blueberries is highly valued by Indigenous communities and other forest food harvesters as a source of income, food security, tradition, and as an alternative to timber extraction on Crown land. By engaging with Aroland Youth Blueberry Initiative (AYBI), Arthur Shupe Wild Foods, the Nipigon Blueberry Blast festival, and Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm and Winery, this collection of case studies demonstrate how foraging increases community food security and strengthens relationships with each other and the land.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

The Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op

Allison Streutker with Charles Z. Levkoe and Connie Nelson, September 2017.

Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op greenhouse. Source: Allison Streutker.

Project Overview: As one of the case studies focusing on the diversity of building a social economy in Northwestern Ontario, the Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op (CLFC) Case Study demonstrates that increasing social capital is one of the main reasons why CLFC was created. The desire to have greater collaboration rather than competition among farmers in this Northern Ontario region means that building connections to foster greater access to local foods within and between communities is a central focus. Consumers can trust their products, knowing they are grown nearby, and producers can take pride in their products, knowing what Northwestern Ontario is capable of yielding.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

Willow Springs Creative Centre

Rachel Kakegamic, Connie Nelson and Charles Levkoe, September 2017.

A WSCC vendor selling a variety of fresh produce. Source: Kakegamic, Nelson & Levkoe.

Project Overview: For Willow Springs Creative Centre (WSCC), relationships and growth through enhancing accessibility are at the essence of their initiatives. Sustainability rather than profitability is the driving force. This type of systems thinking challenges the traditional notions of profit-driven economies. Enhanced sense of purpose and community connections are central foci; money is simply a means of survival for Willow Springs but not the end goal.

As one of the case studies from the Social Economy of Food research series that focuses on Northwestern Ontario, this case study highlights three key food-related initiatives at Willow Springs Creative Center: Horticultural Therapy, Willow Springs Country Market, and Soup and Bread Extravaganza. Through exploration of each initiative, the following research questions are answered: whether and how a social economy of food can/does 1) increase prosperity for marginalized groups; 2) build adaptive capacity to increase community resilience; 3) bridge divides between elite consumers of alternative food products and more marginalized groups; 4) increase social capital; and, 5) foster social innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic diversification.

The full version of the case study is available to download as a PDF.

Video Series

Bringing to Life the Initiatives Making a Difference in the Social and Informal Economy of Food

In an effort to bring to life the value created by the people and initiatives making a difference in the social and informal economy, the Nourishing Communities Research Group has worked with community partners, Nicole Bedford Films and Sheba Films to develop a stunning series of videos. More and more, food connects people who want to make their communities better places to live. Their work creates economic value, but as you will see in these videos, these community leaders are more interested in environmental and social well-being. The Social Economy of Food video series shows what that looks like on the ground—and how these leaders are changing their communities.

The videos run the gamut of social and informal economy activities, from urban gleaning to seeding, harvesting and educating about manoomin (wild rice) production. In the video “Hidden Harvest Ottawa has big dreams for a greener Ottawa. What are yours?” local policy-makers are challenged to look at urban gleaning through a new lens—focused on the hidden benefits produced through waste diversion, social inclusion and food security in their community. Another video from the series, “Durham Integrated Growers “DIG” Community Gardens and All Forms of Urban Agriculture”, shows how a grassroots network can punch above its weight by harnessing the awesome power of volunteer labour to facilitate new food production opportunities and develop new skills. The video “Community Financing is Cultivating Local Food: FarmWorks shows the way” demonstrates how a Community Economic Development Investment Fund (CEDIF) has translated funds from local investors into seed capital for over 90 food and farming enterprises across Nova Scotia. The video “Black Duck Wild Rice: The Resurgence of Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Kawartha Lakes Region” delivers a powerful message on the impacts of colonialism, and the role of manoomin cultivation in community food security and sovereignty, as well as a call for reconciliation.

Visit the Laurier Centre for Sustainable Food Systems’ Youtube channel to watch the Social Economy of Food video series and be prepared to spend some time – they’re addictive!

Relevant Links

Watch “Hidden Harvest Ottawa has big dreams for a greener Ottawa. What are yours?”

Watch “Durham Integrated Growers “DIG” Community Gardens and All Forms of Urban Agriculture”

Watch “Community Financing is Cultivating Local Food: FarmWorks shows the way”

Watch “Black Duck Wild Rice: The Resurgence of Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Kawartha Lakes Region”

References

Bourdieu, P. 1998. Acts of Resistance Against the Tyranny of the Market. New York: The New Press.

Downing, R. (ed.). 2012. Canadian Public Policy and the Social Economy. Canadian Social Economy Research Partnerships. E-book, accessed online at http://ccednet-rcdec.ca/en/node/10641

Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Knezevic, I.(2015). Illicit food: Canadian food safety regulation and informal food economy. Critical Policy Studies. DOI: 10.1080/19460171.2015.1102750

Leyshon, R., Lee, A., and Williams, C. 2004. Alternative Economic Spaces. London: Sage.

Ophuls, W. 2000. Notes for a Buddhist Politics. Pp 369-378 in Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism, edited by S. Kaza and K. Kraft. Boston: Shambhala Publications Inc.

Ostrom, E. 2010. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American Economic Review, 100 (3): 1-33.

Patel, R. 2009. The Value of Nothing: Why Everything Costs So Much More Than What We Think. Toronto: Harper Collins.

Siebenhüner, B. 2000. “Homo sustinens – towards a new conception of humans for the science of sustainability.” Ecological Economics, 32: 15-25.

Teitelbaum, S. & Beckley, T. 2006. Harvested, Hunted and Home Grown: The Prevalence of Self-Provisioning in Rural Canada. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 1: 114-130.

Thompson, M. & Emmanuel, J. (eds.) 2012. Assembling Understandings: Findings from the Canadian Social Economy Research Partnerships: 2005-2011. E-book, accessed online at: http://ccednet-rcdec.ca/en/node/10642