Modesty, Military, and Discomfort: an uncomfortable walk through Mea Shearim

It was the afternoon before our first Shabbat in Jerusalem and we had gone through the Machane Yehuda market to experience the crowds and bargain with street vendors to prepare ourselves for the weekend ahead. This was prior to our visit to Mea Shearim (“One Hundred Gates). This neighborhood is located outside the walls of the Old City in West Jerusalem and was founded in 1848 by Haredi Jews in making their return to the sacred land. Though the community still very much isolates itself from the secular public, nowadays the neighborhood has become part of the expanding city centre as it has become more populated.

Before entering the neighborhood our professors were telling us how the residents of the neighborhood are uncomfortable with tourists. They would normally feel as if they are treated like animals in a zoo, and warned us against taking pictures as a way to respect them.

Once we were in the neighborhood, I immediately felt uncomfortable and even embarrassed. We passed the neighborhood as the residents were preparing for Shabbat, so the shops were closed and the streets were mostly empty—save for a few people who averted their eyes from us and families passing by with small children and baby strollers. It was obvious that we were a tour group as we were walking packed tightly together and taking up the sidewalk, forcing these people to walk on the street around us. We were constantly stopping as our guide pointed propaganda posters to us, which I will continue to talk about later on.

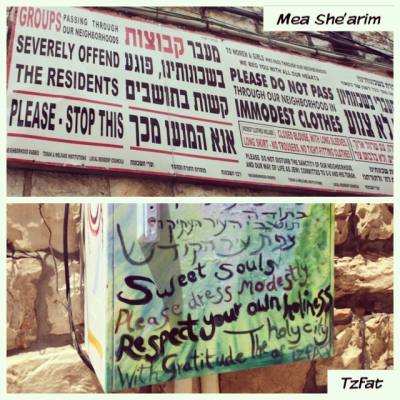

The community has very strict rules of modest dress code, especially for women: a large sign at the entrance to the neighborhood shows the community’s discomfort with people passing through it.

I pair this picture with a painted sign in the city of Tzfat, where we were also expected to dress modestly, to compare the ways in which the people see secular or non-Jews. Fenster talks about how these signs in Mea Shearim are actually illegal in standards of municipality and are not approved or licensed. However, the city of Jerusalem does not enforce the law as the community will only put the signs back up if they are taken down. She also mentions how women who fail to follow these codes are subject to abuse. Though our group was dressed modestly according to the community’s request, I still witnessed women who were not “properly dressed” really treating these people like a public exhibition. Our own group comprised largely of women made it seem as if the boys we were passing by in this scenario were heckling us.

This made me think of our group going through the neighborhood as tourists versus as students—in talking to my classmates, many had voiced feelings of discomfort in going through the neighborhood. This could simply be because we were clearly outsiders walking together in a large group—I wonder what it would have been like if we had gone through the neighborhood on any other weekday, or even at a different time of day. I found the atmosphere of the neighborhood in general to be unfriendly to outsiders, and I kept asking myself why we visited on Shabbat on a day and time when the people clearly did not want us to be there.

The large part of what made me uncomfortable throughout our walk through the neighborhood was the fact that our group kept stopping while our guide pointed out propaganda signs; the ones pointed out to us had to do with the military draft, and loudly translated and explained them to us. The letter to Agunath, determining the secular/religious balance of the state says how “everything must be done to provide the “deep needs” of the religious in order to avoid…dividing the house of Israel in two”. What does that mean for the compulsory military service every Jewish Israeli must complete?

In the abstract of his article, Cohen asks the question of if national religious troops to carry out missions deemed contrary to Jewish traditions. The question is asked of how can one observe halakha while serving in the army, and how there is a conflict of loyalties between their military duties and religious obligations. However, anybody can volunteer to join the military—there are nationalistic, highly religious army groups—those who choose to participate in the socializing force of the military.

From our guide’s explanation, the Orthodox did not participate in the military draft because they needed to study, which he didn’t respect. The community receives welfare from the state, as there is such a huge community of men who go to study Torah and the women have to take care of the children. All these ways the community lives is them trying to protect their culture and community. Whether the way they are doing it is right or not isn’t for me to say. Although the experience was very interesting and sparked many thoughts of how religious extremism is lived and understood, it is an experience I would not like to relive.

Natalia Pochtaruk.

-Cohen, Stuart. “Tensions Between Military Service and Jewish Orthodoxy In Israel: Implications Imagined and Real.” Israel Studies 12. Spring 2007. PROJECT MUSE.

-Fenster, Tovi. “Bodies and Places in Jerusalem: Gendered feelings and urban policies.” HAGAR Studies in Culture, Policy and Identities 11. 2013. PRINT.

-“Status Quo” letter to Agudath Israel: Basis of 1948 agreement for secular/religious balance in new State of Israel: http://hamodia.com/hamod-uploads/2013/12/D35.jpg