On Thursday, we visited the Israel Museum, where we saw the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Model of the Second Temple, and a variety of other fascinating artifacts within the museum itself. We also went to the Knesset, and had a guest lecture on religion and public life in Israel. The readings were focused, then, on the Dead Sea Scrolls and the destruction of the Temples, as well as on Israel’s Law of Return and Holy Places Law. Since we were only inside the Israel Museum for a short amount of time, a number of us went back on Saturday to enjoy the museum without having to worry about time restrictions. For this reason, this blog describes not only what we saw on Thursday, but also Saturday.

Sidnie White Crawford’s article on the Dead Sea Scrolls (“Retrospective and Perspective”) deals with the critical role the Dead Sea Scrolls have had, and continue to have, on the character of Biblical scholarship. Briefly tracing the history of their discovery, White Crawford argues that the Dead Sea Scrolls have had a large impact on modern conceptions of Biblical canon, and the pluralism within Second Temple Judaism. Specifically, the discrepancies between the received Bible and the writings of the Dead Sea Scrolls highlights the differences between Jewish communities, in terms of religious emphasis and ideals, which is reflected in their varying canons. Thus, it is apparent that Judaism was not as monolithic as it claims, but rather, our modern conception of Biblical “canon” in the Second Temple period is anachronistic. Additionally, White Crawford believes that the distinction between canonical and non-canonical works will begin to disappear, as a result of the great significance of apparently non-canonical, but nevertheless significant, works such as the Dead Sea Scrolls within Biblical archaeology.

The other required readings were passages from Josephus and the Talmud about the destruction of the Temples. Both of these texts characterise the folly and iniquity of the Jews as their downfall, which ultimately lead to the destruction of the Temple (though Josephus speaks only of the Second Temple, whereas the rabbis discuss both). Josephus does not elaborate much, but claims, “no generation in history has fathered such wickedness”. Josephus elaborates that the people made “sad moans” at their calamity as they realised that their Temple was gone; a powerful image for Jews throughout the ages, who came to call the Second Temple’s western wall the Wailing Wall. In this way, the passage illustrates the longing and pain of Jews for their own political and religious sovereignty, amidst a world inherently hostile towards them. In the Talmud, rabbis similarly understand God’s theodicy as a punishment, and they specify man’s sins as being idolatry, immorality, and bloodshed.

We also read the Law of Return (that Jews be allowed to “return” to Israel as citizens) and the Protection of Holy Places Law (that holy places be protected and any desecration be a criminal offence), in preparation for going to the Knesset. To me, these readings were helpful as a means of prefacing the tension we saw later at the Knesset between the religious and the secular within Israeli politics. While the tour guide touched upon the religious dynamics of the parliamentary body, these two laws were essential for understanding the root of this relationship between orthodoxy and secular Judaism. Both laws are technically civic actions, set in place by government, and yet they dictate rules based on explicit religious guidelines. This imbalance between religion and state, first introduced in the readings, was further explained and emphasised in the guest lecture we had by Benny Porat, as he highlighted more ways in which civic law and religious law are in conflict. I thought the whole legal aspect of the day, with the Knesset and the guest lecture, was a great way to look at the role of religion within Israeli life and more broadly, the role of God in Israel. As Professor Porat pointed out in his lecture, the North American emphasis on the separation between church (or synagogue!) and state simply does not exist in Israel, as the civic state was established to meet the needs of a particular religious community.

With this integration between religion and policy, however, Israel consequently has a number of unique challenges. For example, the state’s adherence to Jewish law with regards to marriage means that women are often “chained” in marriage to their husbands against their wills, as halachic law requires the consent of both the man and the woman to grant a divorce. Moreover, if women cannot get a “kosher” divorce, and they nonetheless decide to have children with another partner, their children must retain the status of bastard children, which limits them from Jewish marriage. Similarly, homosexual couples cannot marry in Israel, despite the large number of support for gay marriage and rights in a large portion of the population, because halacha does not permit it. Again, since the state follows halachic law on issues of marriage, the government does not offer any sort of alternative to religious (and primarily, Orthodox) marriage, and thus there is no form of civil marriage. In this way, the readings and lecture helped us better understand our visit to the Knesset, and apprehend the complex relationship between Judaism and Israeli law.

And now, onto the Israel Museum – what an amazing place! I was excited to see the Dead Sea Scrolls, but by the end of the tour, I had nearly forgotten about them because there was so much there. Between Danny’s tour and our second visit on the weekend, I think we all were in nerd heaven. First, it was great to be able to see things we have learned about in class, like the Tel Dan Stele, and the silver scroll that serves as the oldest fragment of the Hebrew Bible. But it was also fascinating to learn things I was relatively ignorant about. Even exhibits like the one I went to on dress codes and Jewish wardrobes through the centuries, while not explicitly related to course content or concepts, helped me gain a better perspective of what Judaism has looked like on the ground over the last number of centuries.

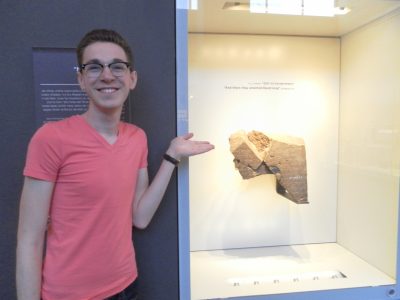

Furthermore, as a Jew, it was extremely overwhelming to see artefacts such as the Passover haggadot, which contained the same text and prayers that are still used today. In religion classes, we often discredit the notion of any monolithic form of religion, as religion tends to evolve in response to external factors and historical contexts. While artefacts such as the Dead Sea Scrolls (in addition to the readings), showcased the clear plurality of Jewish religion over the last two millennia, the haggadot in some ways reaffirmed the power of the Jewish faith for me. It is one thing to know that Judaism has existed for thousands of years; it is another thing entirely to see the evidence of it in front of your eyes. Although I know that we must remain critical of history, even when it relates to matters of religion, I also found it overwhelming being at this museum in Israel and once more in a state of Jewish sovereignty, tracing the history of the Jewish people through the generations. I can admit that my scholarly lens was clouded by my personal biases, but as a Jewish Zionist, I was overwhelmed with an admiration for the tenacity of the Jewish people, as well as a stronger sense of belonging than I have ever felt at the more “religious” sites in Israel, such as the Western Wall. The archaeological evidence may not always support Zionist ideals, but there is nonetheless a clear association (though not necessarily congruity) between the archaeological and Biblical records, and this relationship has greatly stimulated not only my own academic pursuits but also the Zionist dream of statehood in the “historical” land of Israel. (And also, I was just totally geeking out, as my picture with the Tel Dan stele can attest to!)