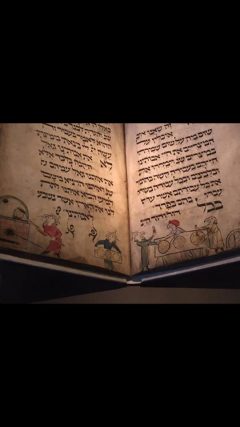

As a child, I spent a lot of time in museums and art galleries. I remember liking the outings; the trips to see paintings and artefacts were rather enjoyable. I have memories of feeling at home in these spaces. However, I also remember feeling alienated. This alienation stemmed from being unable to situate myself in the endless depictions of Madonna’s and Childs hung on the walls of such institutions. Identity and memory are, in many ways, synonymous. Within the walls of museums, memory, as well as identity, is shaped. Furthermore, such institutions work to continually validate those identities as societal contributions[i]. As a child I did not realize there was such a thing as medieval Jewish art or Jewish mosaic (which of course now seems silly). I did not see my identity as a Jew presented within the mainstream institutions I attended. Going to the Israel museums, the museums of the Jewish state, was personally gratifying because I was able to see my identity represented. These museums are places where my cultural past and narrative are centralized in exhibits that display Jewish art and artefacts from the diverse diaspora as well as from Israel.

The Israeli museum is the country’s national museum. The museum plays a critical role in constructing a narrative of a national identity[ii]. As Fiona McLean states, “through the authority vested in them, museums authenticate and present identities through the presentation of heritage”[iii] and also serve to “voice or silence difference and can reflect and influence contemporary perceptions of identities within the national frame[iv]”. The childhood memory quickly fades as the façade of a place devoid of politics, build on the grounds of showcasing art for art’s sake, slowly reveals itself. Cast as a choice between whose voices are heard and whose version of history is told, the museum is inherently political.

The Israeli museum is the country’s national museum. The museum plays a critical role in constructing a narrative of a national identity[ii]. As Fiona McLean states, “through the authority vested in them, museums authenticate and present identities through the presentation of heritage”[iii] and also serve to “voice or silence difference and can reflect and influence contemporary perceptions of identities within the national frame[iv]”. The childhood memory quickly fades as the façade of a place devoid of politics, build on the grounds of showcasing art for art’s sake, slowly reveals itself. Cast as a choice between whose voices are heard and whose version of history is told, the museum is inherently political.

In Israel, a political motive of the state, and of the Zionist movement, is to legitimize itself by emphasising the historical connection of the Jewish people to the land. Influential Zionist scholars viewed archeological exploration as a means to renew a national Jewish identity[v]. This quest has been executed though archeological explorations of ancient Jewish life, contributing to historical narratives which highlight and give legitimacy to certain national identities[vi]. In Israel, archaeology is essentially a national pastime[vii]. Israeli interest in archeology is displayed within my own family, for example. My late relative Aaron Shaffer was a professor at Hebrew University in the Akkadian and Sumerian Language and studied cuneiform tablets.

Community groups and individuals use historical narratives to make claims that situate themselves within the greater context of history and society and to and assert identities[viii]. As Seligman describes, the link between identity and archaeology is both understandable and unenviable. Seligman states “archaeological thought in this genre is predisposed to connect modern human identities with sites and artefacts found in specific territories throughout the world, attempting to create a cultural continuum between ancient and modern peoples[ix]”. The link between land, history and identity merge together into a singular narrative, something that can be told and retold and presented back to the people to consume.

Museums are institutions that translate histories of people into various ideological frameworks and cultural schemas that individuals and groups turn to often as a widely accepted authority on the representation and interpretation of the/their past[x]. Employees at these institutions thereby assume the role of “professional memory workers”, constructing museum exhibits displaying histories[xi]. The art garden of the Israeli museum is an excellent example of this work, as well as the desire to create a synergy between old and new, modern and ancient. The landscape of the garden has a biblical aesthetic setting, with olive trees and tall grass that contrasts with modern sculptural installations whilst concurrently maintaining a sense of unity between the contrasting visual elements. The curator has effectively constructed national identity narratives using environmental elements of the land and modern sculptures to showcase the connection between collective identity and the importance of place. In doing so, the garden translates the Zionist state message that seeks to combine the ancient and the modern and connect a Jewish present/future with the Jewish past of the land.

By: Lx Silver-Mahr

References:

[i] Hanley, Delinda. “Bethlehem Museum Preserves Heritage, Identity, and Culture. “The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs; Washington36, no. 1 (February 2017): 46.

[ii] McLean, Fiona. “Museums and National Identity.” Editorial. Museum and Society, 3:1, (2005):1-4

[iii] McLean, Fiona. “Museums and National Identity.” Editorial. Museum and Society, 3:1, (2005):1

[iv] McLean, Fiona. “Museums and National Identity.” Editorial. Museum and Society, 3:1, (2005):1

[v] Seligman, Jon. “The Archaeology of Jerusalem — Between Post-Modernism and Delegitimization”, Public Archaeology, 12:3, (2013): 181-199

[vi] Seligman, Jon. “The Archaeology of Jerusalem — Between Post-Modernism and Delegitimization”, Public Archaeology, 12:3, (2013): 181-199

[vii]“Archeology in Israel, Part 1.” The Canadian Jewish News. February 26, 2009. Accessed June 03, 2018. http://www.cjnews.com/perspectives/opinions/archeology-israel-part-1.

[viii] Autry, Robyn. “The Political Economy of Memory: The Challenges of Representing National Conflict at ‘identity-driven’ Museums.” Theory and Society 42, no. 1 (2012): 57-80.

[ix] Seligman, Jon. “The Archaeology of Jerusalem — Between Post-Modernism and Delegitimization”, Public Archaeology, 12:3, (2013): 182

[x] Autry, Robyn. “The Political Economy of Memory: The Challenges of Representing National Conflict at ‘identity-driven’ Museums.” Theory and Society 42, no. 1 (2012): 57-80.

[xi] Autry, Robyn. “The Political Economy of Memory: The Challenges of Representing National Conflict at ‘identity-driven’ Museums.” Theory and Society 42, no. 1 (2012): 60.