Happy 105th birthday to the

Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom

It’s a good time to reflect on the virtues of feminist internationalism

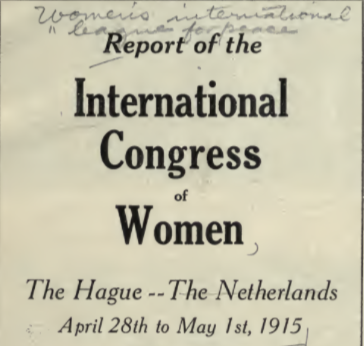

It seems especially appropriate to mark today’s 105th anniversary of the Geneva-based Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which met for the first time on April 28th, in 1915. I say this because, as we grapple with a global pandemic and the conflicting political pressures it has brought to bear on nation-states and our tenuous global infrastructure, more and more news sources have noticed something interesting: that the countries that are among the most successful in balancing firm, knowledge-based responses to the medical crisis with compassion, empathy, and stability, are those nation-states led by women.

It seems especially appropriate to mark today’s 105th anniversary of the Geneva-based Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which met for the first time on April 28th, in 1915. I say this because, as we grapple with a global pandemic and the conflicting political pressures it has brought to bear on nation-states and our tenuous global infrastructure, more and more news sources have noticed something interesting: that the countries that are among the most successful in balancing firm, knowledge-based responses to the medical crisis with compassion, empathy, and stability, are those nation-states led by women.

“Looking for examples of true leadership in a crisis?” asked Avivah Wilenberg-Cox in the pages of Forbes in early April. “From Iceland to Taiwan and from Germany to New Zealand, women are stepping up to show the world how to manage a messy patch for our human family. Add in Finland, Iceland and Denmark, and this pandemic is revealing that women have what it takes when the heat rises in our Houses of State.” It’s a view echoed last week by Jon Henley and Eleanor Ainge Roy in The Guardian. While many male leaders have done well too, they point out, most of the world’s female leaders have excelled: Angela Merkel, Jacinda Ardern, Mette Frederiksen, Tsai Ing-wen, Erna Solberg, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, Sanna Marin, and even Silveria Jacobs, the prime minister of the tiny Dutch Caribbean Island of Sint Maarten, have all shown startling success in managing the pandemic in their respective countries.

Both of these articles insist that we can’t make generalizations about men and women under these conditions. Sociologist Kathleen Gerson from NYU pointed out that women tend to be elected in countries where gender differences are already minimized and trust in government is higher, while men who lead more “traditional” societies find it harder to escape from gendered expectations of what a male leader should be like.

That said, the discussion of the gender dimensions of national leadership is in part a function of the long struggle for women to make their presence felt in politics precisely because many of them believed that women, qua women, could change national and international affairs. This claim has been a complicated one, sometimes veering toward an essentialist argument that women were innately more peaceable than men, and their access to the vote would help “civilize” military-industrial societies. The debate over women’s natures, in the end, has been more complicated than that, but in the international sphere, it was partly set in motion by the formation of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, or WILPF as it is known today.

This brings us back to The Hague in the spring of 1915. The great Dutch “city of international peace and justice,” perched in the edge of the North Sea, and fat with the profits of the Dutch East India Company, was then sandwiched between the Triple Entente and the Imperial German army. Blockaded at sea by the British navy and pinned on its eastern frontier by Kaiser Wilhelm’s Reich, Dutch neutrality was always a perilous thing. So, what brought over 1100 women from across Europe and the North Atlantic world to the city at a time when travel was so dangerous?

They met to try to stop the slaughter. Women’s transnational organizations had been active from the outset of the July crisis. The International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) had been founded only ten years earlier, but in July 1914 it sent a “Manifesto of Women” to the British Foreign Office and all foreign embassies in London. Other female and pro-suffrage groups followed: The British Union of Democratic Control (UDC), followed by the Dutch Anti-Oorlog Raad (Dutch Anti-War Council), the Fellowship of Reconciliation (UK), and then the Women’s Peace Party in the U.S., formed in January 1915 and led by Jane Addams. The Germans also formed the Bund Neues Vaterland, and the Swiss created the Union Mondial de la Femme.

But it was thought that these more or less national or local organisations could not be effective unless they could find “international expression”, and ”that women as such had a special note to strike which they alone could sound.” Thus, isolated women in different countries began finding a different expression, aided by publications that still occasionally crossed borders: the IWSA’s monthly journal, Jus Suffragii, the British Labour Leader, and the German Social Democratic Party’s Vorwaerts.

It was the Hungarian international secretary of the IWSA, Rosika Schwimmer who first proposed, early in the war, a “Conference of neutrals for mediation”, and she traveled from London to the U.S. to convince Woodrow Wilson to lead it, lecturing across the country wherever she was invited. A similar tour by British suffrage activist Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence further awakening American women to this idea, and at least one Canadian. Julia Grace Wales was a Québec-born Shakespeare instructor at the University of Wisconsin. Over her Christmas vacation home to the Eastern townships in 1914-15, she drafted an idea for what she called “Continuous Mediation without Armistice,” and circulated it to Wisconsin peace groups. It became the de facto peace position of most U.S. peace organizations by 1915 and later the basis of the Henry Ford-funded Stockholm Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation in 1916.

Meanwhile, in November 1914, a number of prominent British women signed Emily Hobhouse’s “Letter of Christmas Greeting” to German women, followed by a series of cross frontier appeals by various women, including one from German lawyer and feminist Lida Gustava Heymann entitled, “Call of the Women of Europe.” Socialist women met in Berne in March 1915 and issued a Peace Manifesto of their own. The secretary of the Socialist Women’s International, Clara Zetkin, had naturally defined the war as a symptom of capitalism’s quest for world domination but she placed socialist women’s peace activism in feminist terms as well: “If men must kill, it is women who must fight for life. If men remain silent, it is our duty to speak out.” Paradoxically, precisely because women were not seen as having full political agency (or voice), representatives from all sides of the war were able to gather in Switzerland. The Berne meeting, modest thought it was, marked the first international conference that included “citizens” from both alliances and the neutral countries.

The association of women with peace activism profoundly divided the suffrage movement because it posed risks that, at the very moment women might claim their right to political representation, some of them were taking action against the grain of expected patriotic duty on precisely the ground that women were different from men. As such, the IWSA backed out of holding its scheduled biennial congress in Berlin in 1915 and started to distance itself from those of its membership who saw pacifism as women’s peculiar duty to the international order. Mary Sheepshanks, the outspoken British editor of the IWSA’s journal, Jus Suffragi, and a close friend of Bertrand Russell, dissented from this official stance, and used her position to promote peace as a women’s issue, juxtaposing internationalism and patriotism in feminist terms: “Internationalism rests on the feeling and knowledge that humanity is a bond stronger than mere boundaries of races and states, that above all the superficial barriers in the Western world, a common civilization that unites men and their dependence and their mutual obligations can and should be a way to unite them in a collaboration for the common tasks of civilization.”

In this sense, internationalism was a way to signal the idea of collective self-consciousness that transcended the artificial (a word internationalists of different types used to establish a boundary between what was natural and what was a function of the exercise of domestic power hierarchies) collectivities of race and nation, something more akin to cosmopolitanism but which preserves space for the cultural attachment to nation that operationalizes the concept of political rights and duties. In Sheepshanks’ opinion, internationalism as a higher location of political attachment was sustained during the Great War as one of the universal treasures that feminist women were trying to keep alive, as living proof of these ideals as political practice. Jus Suffragii was one of the few international organs that produced reports of political activity from both sides of the war.

And women were indeed prepared for this role. The British feminist and internationalist Emily Hobhouse took this view when she wrote: “The International Suffrage Alliance had not in vain been training women for years from all parts of the world to know and work with each other, and though officially it stood aside, yet one of its most noted members—Aletta Jacobs—belongs the honour of concentrating and shaping the ardent yearning of women of all lands for peace and justice.”

Alletta Jacobs was then the president of the Dutch Association for Woman’s Suffrage, and its Committee for International Affairs. From that position, she invited all women who were interested in the cause of peace to come to The Hague in April 1915. Jacobs used the IWSA’s mailing list, arguing that it was never more important for the women of the world to meet: “the women have to show that we at least retain our solidarity and are able to maintain mutual friendship.” Jacobs still considered this to be the international business meeting of the IWSA, but one in which women could also freely discuss the situation of the world.

At this point, British suffragist Chrystal Macmillan privately canvased members of the IWSA to suggest that after the “business meeting”, delegates could stay to hold another on issues of international arbitration, public control of foreign policy, and the prospects for peace. If the Alliance didn’t want to sanction this kind of meeting, internationalist women could convene it anyway. Once the IWSA formally signalled that it would not back anything that moved beyond the issue of suffrage, Jacobs called a preliminary planning meeting in Amsterdam on February 12 and 13 with a view to following Macmillan’s proposal. The meeting had representatives from both sides of the war (Belgium, Britain, Germany) and one neutral (Netherlands).

But the most important country still missing at that point was the United States. It was the neutral state that most held the hopes of the world peace movement. While President Wilson continued to rebuff efforts by peace groups to lead mediation efforts, the formation of the Women’s Peace Party in Washington in January 1915, with future Nobel Peace Prize winner Jane Addams at the helm, was profoundly encouraging for Jacobs and her organizing committee. Addams accepted the invitation to The Hague and brought a large American delegation with her (47 either crossed the Atlantic or arrived from other European locations), including another future Nobel Laureate, Wellesley College economist and sociologist Emily Greene Balch. This gathering of neutral and belligerent citizens during the war was only possible because of what Balch noted in a letter home: that women had a peculiar locus standi as non-citizens, as people subjected to decisions over which they had no say, to speak against war.

About 1136 women (most of them Dutch, of course, but 12 countries were represented) met between April 28 and May 1. There were over 1500 at its opening and because this was too large a number to fit into the Carnegie-built Peace Palace, the Congress had to gather in the Dierentuin, the great hall of The Hague Zoological Gardens. Not all European feminist groups were represented, even by correspondence: the principal French suffrage groups argued that the object of suffrage was to participate in the public life of their nation, not abandon it to the ether of internationalism and pacifism. The Conseil National des femmes françaises (CNFF founded in 1901) and the Union française pour le suffrage des femmes (UFSF, founded in 1909), issued a counter-manifesto. “We have finally understood that our primary obligation amidst the great misery that afflicts our country, is to pull together and become one single and solid family, the family of la patrie.’’ Marguerite de Witt-Schlumberger, head of UFSF, sent five sons to the front. Jane Misme, editor of the feminist journal, La Française, attacked pacifism “as orchestrated by Berlin.” French feminists, she tried to claim, wrongly, were never internationalists.

The Hague Congress debated war and peace for three days, and then issued a Manifesto filled with what would later become the standard positions of liberal and socialist internationalism: arbitration, the right of self-determination, democratic control of foreign policy, disarmament, the rejection of all “annexationist” war aims, the channeling of international public opinion through a new society of nations, and, most of all, the international enfranchisement of women (more on that later). Despite the common currency of most of these ideas, they were targeted in the press for their gender (“a screeching sisterhood,” “twittering sparrows,” “babbling,” “hysterical”). They were ridiculed for being both excessively feminine for international politics (women are too sensitive to understand war) and too unwomanly for domestic politics (they were stepping into political areas that demeaned their femininity).

The Hague Congress did two things of historic significance. First, it formed itself into an international organization called the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace (ICWPP) based in Amsterdam during the war. Jacobs was its secretary but Addams became the organization’s president from her home base in Chicago. In 1919, at its next Congress in Zurich, the ICWPP changed its name to the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and established a headquarters in Geneva to lobby the newly formed League of Nations. Addams was still president but day to day operations were run by fellow American Balch as its full-time secretary. Today WILPF retains offices in both Geneva and New York City, but The Hague Congress is why it marks today as its founding moment.

The second thing The Hague Congress did was to send two delegations of women to the capitals of Europe in May and June 1915 to circulate its idea of “continuous mediation”. Addams, Jacob and Schwimmer met with the leaders of Netherlands, Britain, Germany, Austro-Hungary, Italy, France, and Belgium. Balch, Schwimmer, and Chrystal Macmillan from the UK, went to Scandinavia and Russia (although Schwimmer was refused entry to Russia). This in itself was extraordinary, and while these envoys were of course unable to stop the war and were subject to ridicule in the patriotic press in their home countries, their peace proposals were received with, for the most part, respect and seriousness. According to Addams, Austrian Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh remarked at their meeting: “You are the only sane people who have been in this room for ten months.” Wilson, too, when Addams took The Hague resolutions to him later in the summer, stated that they were “by far the best formulation which up to the moment has been put out by anybody.”

There is some debate amongst historians, of course, about how influential The Hague resolutions were on the subsequent trajectory of Wilson’s internationalism, but WILPF undoubtedly represented an influential internationalist community actively lobbying the administration for the rest of the war. By 1919, when WILPF held its second Congress in Zurich, it still held out hope that Wilson’s internationalism would bring to the table their more radical feminist hopes, but they ended up being deeply critical of the League of Nations as it was constructed at the Paris Peace Conference, and even more hostile to the annexationist tendencies of the final terms. To them, the peace process was an abandonment of everything the internationalists had fought for during the war.

They also waited in vain for the international community to sanction women’s political rights as a constituent part of international peace. While the end of the war brought suffrage to more women in the Atlantic world, it came fastest in those states that had been neutral or, as in Russia and to some extent Germany, had experienced a socialist revolution. Stalwart members of the Entente France and Italy only granted women the vote after the Second World War. There was no automatic correlation between women’s patriotic loyalty to the warring state and their emancipation as full citizens.

The abject failure of WILPF to stop the war or to secure a more just peace puts it in the same company of all other liberal and socialist international groups. But The Hague Congress nevertheless marked the start of a bona fide “feminist internationalism,” a term used at the time by the international members of the group to define what they were trying to build. WILPF’s critique of the early League of Nations—which was subjected, of course, to numerous criticisms at the time and after—was the only one that insisted its failings had something to do with gender.

What did this mean exactly, given that the term gender was not used in this sense until the 1950s?

If we look at the WILPF’s early Congresses and subsequent work in Geneva, it’s clear that, just as socialists saw the meaning of international politics in terms of global class conflict, WILPF believed that the subjugation of women, starting with their political rights but including all forms of social marginalization and exclusion, reproduced a culture of male leadership that valorized militaristic nationalism and imperialism.

Their intellectual stimulus, if you will, came from two experiential sources. One was from working together as an international organization across borders during a time of war, subjected to shared forms of press ridicule along gendered lines, as well as varying degrees of police harassment. Their transnational cooperation against the grain of hyper patriotism, created an international sense of feminist consciousness, as they recognized the marginalization of women as a global phenomena, and a central part of international politics.

They knew perfectly well that most women didn’t share their pacifism, either because of patriotic loyalty or fear that pacifism would hurt suffrage. But because they identified the cruelty and waste of the war with the peculiar pathologies of nationalism, they foregrounded humanity rather than nations as the proper focus of building permanent peace; and one cannot speak of humanity without women.

The second source of knowledge stemmed from the fact that almost all of them were social workers of some type. Many of them had developed a sociological perspective on the nation-state itself. Across the North Atlantic academic world at this time, nationalism and internationalism were being studied as specific forms of social identity, and the social settlement work of Jane Addams in Chicago, the studies on immigration by Emily Balch, the challenges to marriage laws in Germany by Anita Augspurg and her partner Lida Gustava Heymann, among many others, all proposed that there was something social-psychological about nation-building that needed to be understood if we were to understand war.

But this posed a dilemma. Feminist internationalists were also radical democrats who believed that the best way for women to influence international politics was through suffrage; their assumption was not that women would automatically be pacifistic when they got the vote, but that as equal citizens, women would bring less docility to national life than they did as social and political supplicants; and men, freed of the need to repress women and thus magnify their masculinity, would be less enamored of the need for heroic violence. A feminist internationalism would transform the social role models of men and women simultaneously, releasing them both from relations of dominance that made force an international norm.

In this sense, WILPF rejected any essentialist idea that women were inherently, or biologically, more peaceable and men more aggressive and violent. It was the cultural relationship of men to women which created the destructive norms of leadership that afflicted the world. Undo that, and everyone will be better off.

What WILPF argued during the war and in the 1920s anticipated the “human security” project of the late 20th century. In incipient form, its principal tenets found their way into the UN’s Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda between 2000 and 2019, Sweden’s formal adoption to a feminist foreign policy in 2014, and even Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy in 2019. And so, for that reason, WILPF’s early history is worth remembering and understanding. It is today being retrieved by feminist international relations theorists as part of the genealogy of an alternative to the realist-idealist or liberal-radical dichotomies that have limited the way we think about international politics. It also hints, I think, at why we should not be surprised that so many women leaders around the world have handled the global pandemic so well: in crisis, the politics of humanity works better than the politics of exclusion.

Andrew M. Johnston ©

WILPF’s website is at: https://www.wilpf.org