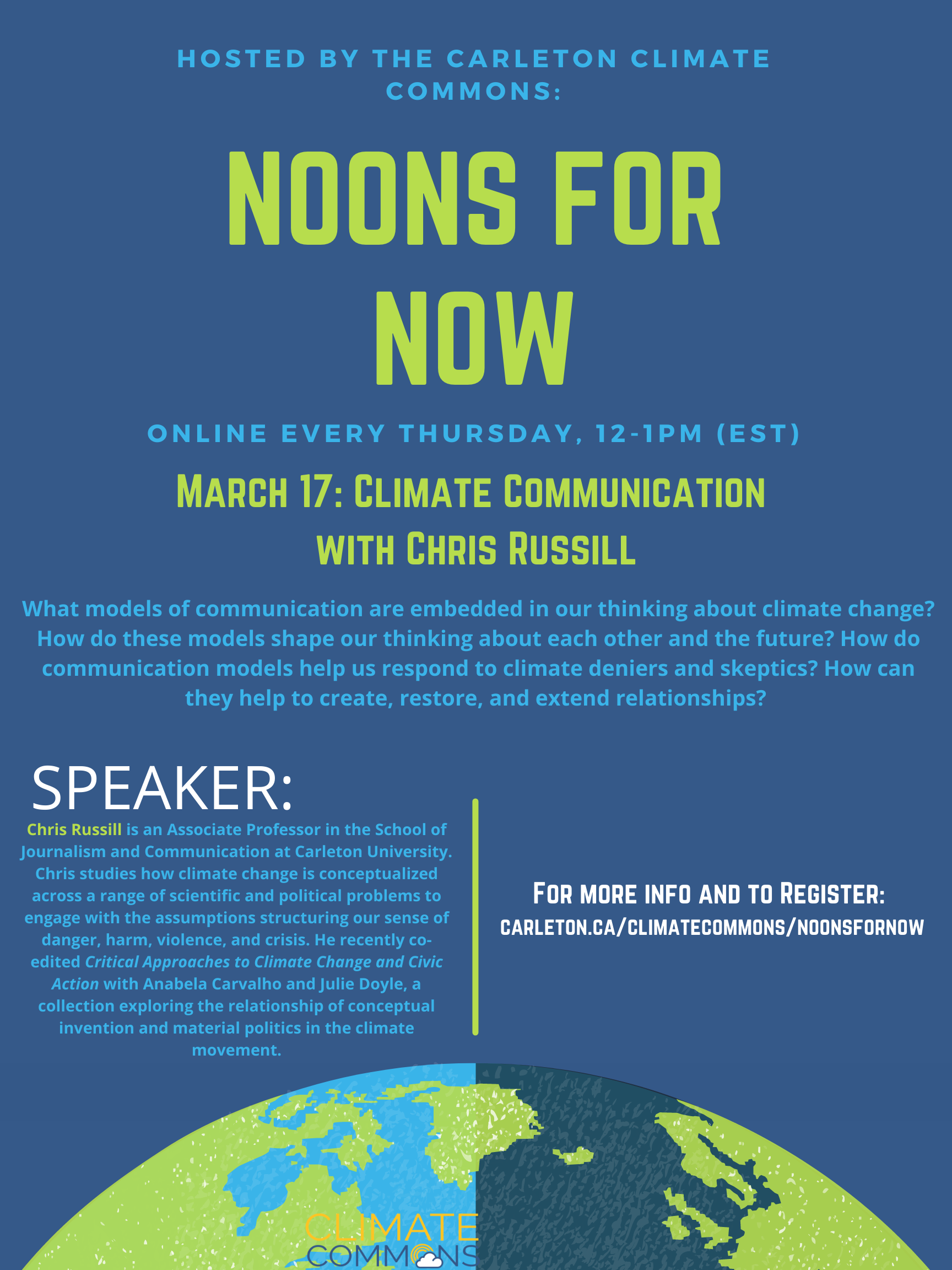

Chris Russill is an Associate Professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University. Chris studies how climate change is conceptualized across a range of scientific and political problems to engage with the assumptions structuring our sense of danger, harm, violence, and crisis. He recently co-edited Critical Approaches to Climate Change and Civic Action with Anabela Carvalho and Julie Doyle, a collection exploring the relationship of conceptual invention and material politics in the climate movement.

The Impact of Framing on Climate Action

Chris Russill noted the point of the Noons for Now on Climate Communication very early in the meeting. He argued that the frames that we use to talk about the climate crisis must be rethought. The main fames by which we talk about the crisis have always been based on scientific and technical communication; but does scientific communication really convince people that we need to do something? According to Professor Russill, the answer seems to be no. We need, instead, to appeal to people’s emotions when talking about the climate crisis. Maybe anyone who wants to understand the science behind the climate crisis already understands enough to be motivated to take individual or engage in collective action. In that case, we need to communicate our feelings of climate grief, anxiety, or any other worries to try to reach those who still don’t care. Finding new ways to relate to people and engaging in a wider range of communicative models about the climate crisis is essential to overcoming these challenges. Rethinking how we communicate is especially important because these same feelings are also why people can be convinced to deny that the climate crisis is even happening. Disinformation campaigns are designed to appeal to these emotions, they give people privileged information and allow them to be part of an ‘in group’. Oil and gas companies and political actors have created strong identities around oil that people can hold on to by using their fear of the future and by appealing to people’s inherent biases. Nobody has the time to debunk every climate denialist, nor does that even really work. We need to work to build a vision of a just recovery that everyone can be on board with. We must focus on communicating the transition away from fossil fuels as being a social justice issue rather than a technological issue, and make sure our vision of the future doesn’t contain the same inequities as the present.

written by David Baker.

David is a fourth-year student at Carleton University pursuing a Bachelor of Arts Honours in Political Science. David’s main academic interests are environmental policy, the politics surrounding contemporary ‘democratic decay’, and East Asian politics and history.

Resource List

The following is a list of resources recommended by attendees at our event.

Key Texts:

Kari Marie Norgaard, Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, 2011.

Stephanie LeMenager, Living in Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century, 2013.

People lists / online sites for debunking misinformation and identifying fossil fuel influence:

Desmog Blog (PR and disinformation debunked)

Inside Climate News (journalists covering oil and gas, largely in US context)

Real Climate (scientists parsing events and debunking skeptics)

Understanding Skepticism, Doubt, and Inaction:

Yarimar Bonilla, “The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA,” Political Geography, 2020.

Yarimar Bonilla and Marisol Lebrón (Eds.), Aftershocks of disaster: Puerto Rico before and after the storm, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2019.

Mike Hulme, Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity, 2009.

George Lakoff, “Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment,” Environmental Communication, 4:1, 70-81, 2010.

Amanda Machin, Negotiating Climate Change: Radical Democracy and the Illusion of Consensus. London: Zed Books, 2013.

Robert Neubauer and Nicolas Graham, “Fuelling the Subsidized Public Mapping the Flow of Extractivist Content on Facebook.” Canadian Journal of Communication, 46, 4: XXXX, 2021

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt (2011 book and 2014 film)

Erik Swyngedouw, “Apocalypse forever?: post-political populism and the spectre of climate change.” Theory Cult. Soc. 27, 213–232, 2010.

Chris Russill, “The “Danger” of Consensus Messaging: Or, Why to Shift From Skeptic-First to Migration-First Approaches,” Front. Commun., 2018.

“Overcome Fatalism By Talking Solutions, Climate Communicators Urged,” The Energy Mix, April 19 2022.

Imagining Ways Forward:

Peter Berglez, and Ulrika Olausson, “The post-political condition of climate change: an ideology approach,” Capit. Nat. Soc. 25, 54–71, 2014.

Anabela Carvalho, and Tarla Rai Peterson, “Reinventing the Political: How Climate Change Communication Can Breathe New Life into Contemporary Democracies (Pp. 1-28),” in A. Carvalho, and T. R. Peterson. Editors Climate Change Politics: Communication and Public Engagement,2012.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), “Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty.” Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization, 2018.

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

Jens Marquardt, “Fridays for Future’s Disruptive Potential: An Inconvenient Youth Between Moderate and Radical Ideas.” Front. Commun. 5:48, 2020.

Chantal Mouffe, For a Left Populism. New York: Verso, 2018.

Petersen, M.B., Christiansen, L.E., Bor, A. et al. Communicate hope to motivate the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports, 2022.

Mimi Scheller, Island Futures: Caribbean Survival in the Anthropocene. Duke University Press, 2020.

Kyle Whyte, “Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene.” English Lang. Notes 55, 153–162, 2017.

Kyle Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises.” Environ. Plann. E: Nat. Space 1, 224–242, 2018.

Robert at Children’s Climate Championship Interviews, playlist on YouTube.