An update to our DCHU Irregular newsletter about the goings-on around the DH Program at Carleton U

Wen considered the nature of time and understood that the universe is, instant by instant, recreated anew. Therefore, he understood, there is in truth no past, only a memory of the past. Blink your eyes, and the world you see next did not exist when you closed them. Therefore, he said, the only appropriate state of the mind is surprise. The only appropriate state of the heart is joy. The sky you see now, you have never seen before. The perfect moment is now. Be glad of it.

-Terry Pratchett, Thief of Time.

Where did the term go? I swear it was here a moment ago. There’s still so much left to do… When I get a bit overwhelmed by time speeding up, the blink-and-you’ve-missed-it way things change slowly then all at once, I find re-reading Terry Pratchett to be of some help. Give him a try!

In this edition

- AI and its intersection with the work of Terry Pratchett

- Laura Horak & Colleagues win prize!

- Check out the Protohyve

- Sean Muncaster reports from MIGS

- DIGH5000 Nuts and Bolts

I spend far too much time thinking about AI. It leaves me tired. How about you?

This edition of the DHCU Irregular will ideally reach you later today, though Carleton’s email filters will probably put a lot of it directly in your trash folders. Hmmm. Computers, eh? AI will do everything eh? Resistance is Futile! Sublimate yourself in the beauty and terror of the machine! And yet, we can’t configure an email filter correctly.

At this point, I’m reminded of some more Terry Pratchett. In one story, an information revolution comes to the Discworld. Semaphores married with a theory of information create a network of towers across the world, called the ‘clacks’. In order to keep the system in step, messages about messages are sent backwards and forwards – this is called the ‘overhead’. When a key figure amongst the clacksmen, John Dearheart, dies in mysterious circumstances his name is put into the overhead so that it travels up and down the system forever: he lives on in the metadata. In a different story, the backwards country of Borogravia tears down the clacks prompting a military intervention. The Borogravian god, Nuggan, has declared the Clacks an abomination. Yet it transpires that the god Nuggan is largely an empty shell. Prayers of the faithful echo backwards and forwards inside the shell, recombining in bizarre ways, turning up back on earth as new ‘abominations’. As Commander Vimes says, it’s hard to believe in a god who might be wearing their underpants on their head.

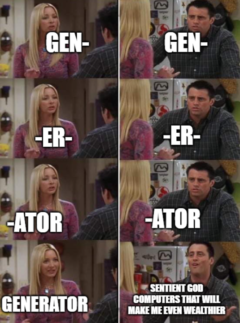

My none-too-subtle point here is that modern LLM, conventionally called ‘AI’, are rather like Nuggan (and are similarly surrounded by people who will claim almost anything in their name). And like John Dearheart, there are ghosts throughout the metadata who still cast shadows (at the risk of shameless self-promotion, I gave some talks along these lines recently). All data is filled with ghosts and spirits. Part of DH is learning to listen to what they’re saying.

Remember Nuggan, that’s all I’m saying.

Remember Nuggan, that’s all I’m saying.

Before you go exploring LLM, remember Nuggan, remember John Dearheart. And maybe read some Eryk Salvaggio. Perhaps you’ll need this typology of skepticism around LLM. (I’m in at least three different flavours). Round that out with this history of AI through three key datasets which, more than anything, suggests why I fear that learning management systems and all that data might become irresistible for cash-strapped institutions looking for ways to plug fiscal holes. I have a long history of being wrong about… well, a lot, so here’s hoping Wen is right.

Happy news!

The DH programme, faculty, and students, are pleased to congratulate our friends and colleagues led by Dr. Laura Horak for winning the American Studies Association’s Digital Humanities Prize for their work on the Transgender Media Portal! Well done!

About the Transgender Media Portal

Too often people think that trans+ people have hardly made any films. In fact, trans+ people have created thousands of films spanning various genres such as horror, comedy, romance, documentary, animation, drama, and more. They’re just hard to find. That’s where the Transgender Media Portal comes in!

The Transgender Media Portal is similar to IMDb but it’s exclusively focused on highlighting the work of trans+* creators. Jump through the Portal to explore thousands of trans-made films, television shows, and online videos! You can search for media created by specific types of artists, like “comedy films by trans Indigenous artists,” or “music videos by Black transfeminine artists.” While we don’t host the films ourselves, we provide links to where you can watch them–whether it’s through streaming services, on DVD, or in an archive.

Our primary focus is on artists from Turtle Island (North America), but we also feature creators from other regions. We are particularly enthusiastic about showcasing the works of Black, Indigenous, POC (people of color), intersex, and Deaf and Disabled filmmakers.

The Transgender Media Portal is an ongoing project developed by a dedicated team of student scholars, artists, designers, and developers at the Transgender Media Lab at Carleton University, which is situated on the unceded territory of the Algonquin Nations, known colonially as Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. We are also partners with the Data+Humanities Lab at University of Ottawa.

We have received funding support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation, and Trade. Additionally, we benefit from in-kind support from Carleton University and the Audiovisual Research Centre at Carleton University.

Studio DH News

This past fall, Dr. Amanda Montague has been crafting a protocol and approach for working in good relationship with the various communities within which and with whom we live. Amanda has been ably supported by her research assistant Liran Assaf. It’s exciting stuff, and we hope in the next issue we can begin to reveal some of what we’ve got on tap at the intersection of research, ‘research-creation’ as SSHRC puts it, and our initial partnerships.

In this year’s DH cohort, we’ve been able to support students not only in general terms, but also for specific professionalization opportunities. Sean Muncaster, for instance, reports on his recent participation at the Montreal International Games Summit at the end of this newsletter, reflecting on what it might mean to teach games through the humanities. He says, ‘I’ve just never really done anything within this sort of financial support framework before … I would really love to start seeing how I can fit into that industry and the Indie showcase in particular seems like a phenomenal opportunity to begin meeting people… Would this be appropriate?’

YES!

Being able to say yes is probably the single greatest thing about the job and what the StudioDH gift offers us!

You should check out: Protohyve

There are so many interesting things going on around here. You should spend time exploring Protohyve, a project of our colleague Stéfy McKnight and team:

PROTOHYVE seeks to create a constellation of artists, curators, scholars, and professionals to generate new ways of understanding and framing research-creation in so called Canada. PROTOHYVE is a resource based centre for research, that invites collaboration between research-creationists and labs across Turtle Island to share ideas, successes, challenges, artwork, and resources.

DH Program Nuts and Bolts

- DIGH5000 resumes in the winter with participants leading us through their engagements with particular dimensions of this thing DH

- The Coding Workshop for Humanists was a resounding success: thank you to Martha Attridge-Bufton and Chantal Brousseau for guiding us

- Keep an eye on the library for details on an upcoming workshop on metadata

- Also, I think we’re going to be organizing some low-key socializing. Watch this space!

- Remember to keep lodging your reports, gang, re DIGH5000 activities

Observations from MIGS on How We Might Learn with Games – Sean Muncaster

[I came up with that title; titles are clearly not my strong suit. -SG]

The Montreal International Games Summit opened on the topic of resiliency in the gaming industry, riding out the inevitable downward slope following a surge in gaming interest during the pandemic. With cuts to many studios, the emphasis on how to reconfigure story-telling and cater to consumer interest in a tumultuous time for the industry began to take on an eerily similar tone to discussion I’ve been steeped in in the past. What I’m referring to is discourse surrounding the ‘death of the novel’ and the idea that there will be a constant battle between content creators and the consumers that somehow always seem to be consuming stories the ‘wrong’ way, inconveniencing those trying to ‘elevate’ narratives into grand epics that often fall flat in the face of changing societal values on leisure time.

Often repeated on the panels was the notion that the industry must move away from singleplayer marathons boasting hundreds of hours of campaign playtime; a less is more attitude seems to be becoming dominant as gamers yearn for the ability to complete a digital narrative without devoting months of free time to a single game. Market analysis touted a sweet-spot existing in the twelve-to-fifteen-hour range, enough time for a player to become deeply invested in the game and adept at its mechanics, while wrapping up before it begins to be seen as a slog. Monstrous, unending narratives like Eldenring certainly deserve their time in the spotlight, but it simply becomes unreasonable to expect the average consumer to spend the upwards of one hundred hours it takes to absorb the full experience. In this sentiment the echoes of English department debate are clear: the rise of the short story over the traditional novel as the principal object of study in secondary education has been a point of serious chagrin, with the possibility of fresh faces to universities never having read a novel cover-to-cover becoming a strange new reality.

Despite these similarities, even the longest of novels I’ve had to study academically fall well short of the playtime required for some of the lengthiest game narratives; I would be frankly distraught if I was ever assigned more than just one book of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, nevermind learning that I would be expected to finish Eldenring in time to be evaluated on it at end of term. As we settle into a world where fictional game narratives are welcome in humanities departments, how do we begin to categorize what sort of game length is appropriate for a class setting? I would adore the opportunity to teach Bioshock, a game that Steam clocks my playtime at as 13.5 hours – right in the sweet spot discussed above – but how much of my experience with that game was accelerated by a massive amount of experience navigating game spaces and learning to anticipate mechanics and map layouts? Just as the promising student of English will continuously develop tools to glean meaning from the word with greater and greater efficiency, so too does the avid gamer inevitable develop transferable skills between a vast swath of game genres.

Does the gaming industry’s shift towards game narratives in the twelve-to-fifteen-hour range suddenly make mainstream titles eligible as assigned ‘readings’? Unfortunately, that still seems unlikely. A recent visit to Carleton’s Experiential Learning Hub was the closest opportunity I’ve had to gaining fresh insight into what it means to learn to navigate a digital space: a pair of virtual reality experiences lasting a mere seven minutes for the first and a half hour for the second had me reeling through their environments, and I was shocked at how little information I retained when so much of my focus was on simple existing in and interacting with the mechanics of the experience. It stands to reason that a class of scholars exposed to a game like Bioshock for the first time would have similar experiences, and the variety in skills foundational to navigating gamespaces would create wildly different playtimes required to cover the game if it were to be used as course material.

Aside from listening to the panels, my most valuable conversations were with the indie developers showcasing playable demos of their upcoming games. What I wanted to get out of this was an understanding of how the creation of mechanics and narratives worked in tandem during game development. I knew that I would be putting devs on the spot with a question like this – the event is very much geared towards connections within the industry, and it’s unlikely that they were preparing for the first-thing-in-the-morning interaction to be a fresh-faced student attending his first industry event.

Two teams had excellent answers for me: Borealys Games showing off their upcoming roguelite Echoes of Mystralia, and Woodrunner Games with their pure platformer Croak.

Echoes of Mystralia was the first demo I had a chance to try. Certainly reminiscent of Hades, this fast-paced, jumpy but smooth roguelite features a highly customizable ability upgrade system where starting weapons and spells provide the foundation for uncovered bonuses to be added onto freely; no upgrade is tied to a specific weapon as one might expect from most games in the genre.

As I learned from a discussion with the Borealys representatives, where these mechanics intersect with the game’s narrative is in the upgrades’ description as memories. The player-character seems to be piecing together fragments of their past abilities, reconstructing their powers in a form that resembles but never quite matches how it might have been before. The presentation of upgrades as memories gives a sense of linked narrative and gameplay progression over the course of successive runs, a confluence that can be difficult to pull off in a genre that inherently has the player starting from scratch over and over. The more you play, the more you remember, both of the story and of the game’s mechanics.

Croak focuses less on tying their mechanics to the narrative, but more on bringing an aesthetic that complements the difficulty of the game. Wielding the power of a frog prince’s elastic, bouncing tongue, players navigate a hardcore platformer with the expectation of dying fast and dying often. The Woodrunner team emphasized that the cutesy art style of the game (featuring some lovely Canadian critters and gorgeous hand-drawn backgrounds) was in part an attempt to ward off the frustration of repeated deaths, creating an atmosphere of levity that would make it easier for players to bash their heads – and tongues – into the wall over and over. The name itself puns on this: you’ll be croaking (making adorable frog noises) and croaking (facing unfortunate deaths) quite often.

See you soon

That wraps up the Fall 2024 term in the DH program at Carleton University. Blink. Blink.

Please feel free to share! This edition of the DHCU Irregular -aside from the bit written by Sean Muncaster who so graciously shared his experience with us- was written by Shawn Graham to whom all blame obtains: shawn.graham@carleton.ca

Previous editions of the DHCU Irregular were courtesy of Buttondown and may be read here; unfortunately, there were simply too many issues with our Carleton email domain servers eating every issue and many people not receiving them. We will post here until we come up with a better solution.